Never fear, a moral expert is here

Editorial Assitant: Stella Wernicke

Note: This article was already reviewed and is published in the German version of In-Mind.

Can I read the diaries of my deceased daughter? Can I tell a friend's family that they have a drug problem, even if they have asked me to keep it quiet? Many people are confronted with tricky moral decision-making situations in the course of their lives and seek the advice of friends, family members, or even experts. But is there such a thing as moral expertise? At the interface between social psychology and philosophy, this article deals with the question of whether moral expertise can exist and who could be a moral expert.

Fig 1: What is right, what is wrong, and who can advise on moral decisions?

Fig 1: What is right, what is wrong, and who can advise on moral decisions?

How do I decide when all courses of action have negative consequences?

Am I obligated to put one person's life on the line if it means I can save a group of people? Can I put one human life above that of another? For a long time, these were merely thought experiments in which moral dilemmas and their all-unfavorable behavioral options were analyzed. Now these thought experiments are becoming reality when it comes to programming autonomous vehicles, for example, because in the worst-case scenario they have to determine which life has priority. At the beginning of the COVID-19 Pandemic, there were voices saying that the old and the weak should sacrifice themselves for the good of the rest of the population. Moral issues are not limited to matters of life and death, however, because what is morally right or wrong is often tricky in everyday life as well: Should I point out to the waiter that he forgot a dish on the bill? Can I make a colleague's mug with sexist motifs disappear? For both small or large moral decisions, who can help with these questions or even make a decision on behalf of someone else?

With everyday moral problems, one can already turn to a wide variety of places for an "expert opinion." There are newspaper columns, radio shows and podcasts that deal with the moral problems of readers and listeners. They reflect on the underlying issue and try to give an answer: "The question of conscience" (Original title: "Die Gewissensfrage"; Süddeutsche Zeitung, Germany, until 2018), "A question of morality" (Original title: "Eine Frage der Moral"; Life Radio, Austria), "The Ethicist" (The New York Times Magazine, USA) are just some of the more prominent examples. What or who qualifies the authors of these popular formats to answer moral questions? Is it their formal qualifications (one is a medical doctor and lawyer, two are philosophers)? Are they particularly suited in character to provide moral guidance? For what reasons do those seeking help trust the advice of these individuals?

What is (moral) expertise?

Expertise means, first and foremost, a great deal of domain-specific knowledge. Furthermore, experts are characterized by their ability to consistently solve problems in their field, efficiently, and in an excellent manner, making few mistakes. In addition, experts are particularly good at processing a lot of information due to their intensive training and years of experience, and they remain competent across many complex situations [1]. Expertise is studied in many different fields, such as academic professions (e.g., mathematics), sports (e.g., tennis), or strategic thinking (e.g., chess). Applying this definition to the field of moral decision-making, two questions, among others, arise: 1) What does excellence mean in this field? 2) What specific knowledge or type of experience is required?

What does excellence in moral decision-making mean?

Can moral expertise exist at all if there are no objectively correct answers? In order to develop skills, people need feedback on whether they have made the "right" decisions because this is the only way to adapt decision-making strategies and behaviors. In other domains, performance can usually be measured quite objectively and thus excellence can be determined – in sports (competitions won), in academia (publications), or even in the arts (sales figures) – but what yardstick can be applied to moral decisions that have yet to be defined? While certain moral issues are fairly clear-cut – these include lying, stealing, or even cheating – there is more room for debate on other issues. For example, is it okay to refuse to help an unsympathetic, unpleasant, and consistently antisocial colleague who suddenly needs it due to illness [2]? There may be quite different approaches here, depending on which rule is followed. One could decide according to the proverb "What goes around, comes around": If the colleague himself has never helped anyone, he cannot now expect others to do so either. Alternatively, one could act according to the rule that those in need of help should be helped in principle, regardless of personal sympathies. Even though this more altruistic decision may appear to be of higher moral quality, does it make it objectively more correct than the other?

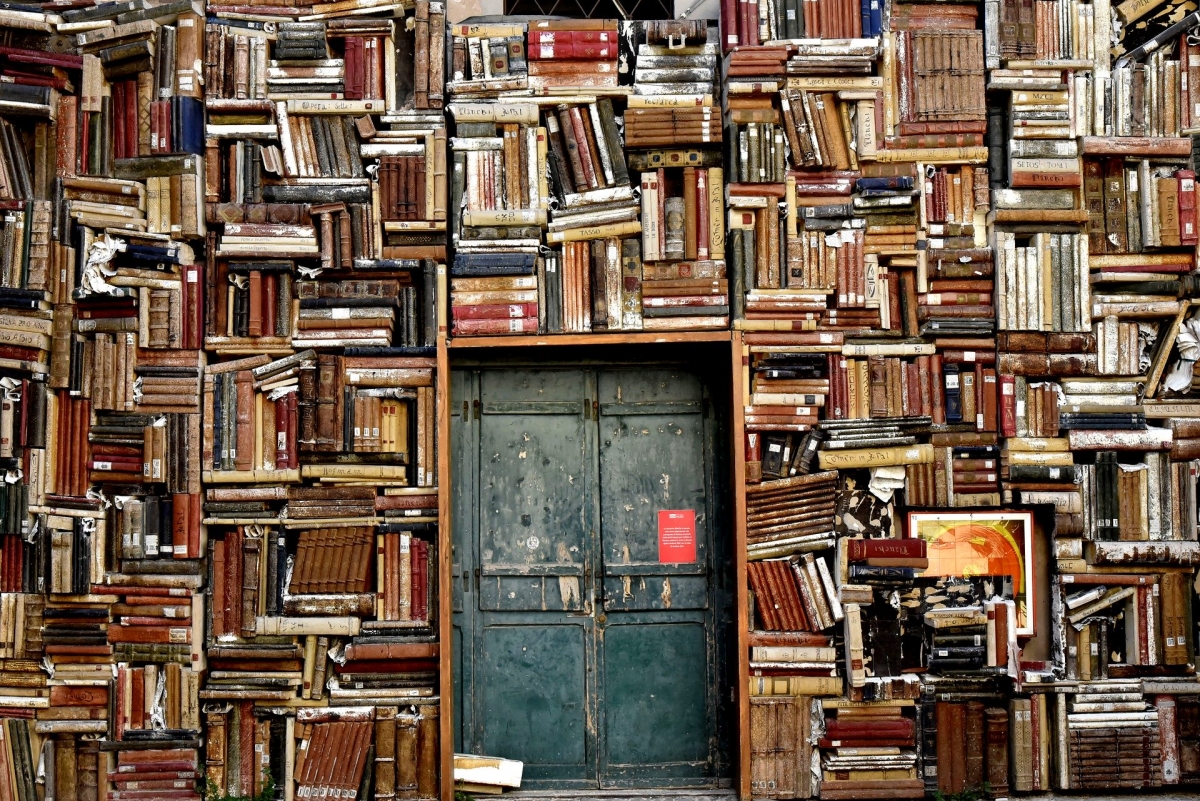

Fig 2: What would be the right moral decision here: divert the train or let it continue straight ahead?

Fig 2: What would be the right moral decision here: divert the train or let it continue straight ahead?

In the thought experiments mentioned at the beginning, this becomes even clearer [3]. Imagine having to decide: divert the train or let the train continue? Sacrifice one worker to save five? The answer options here are presented in deontological terms (that the rule "thou shalt not kill" is upheld, and the train is not actively rerouted, with the result that five track workers die by omission) and utilitarian terms (a utility calculation is involved, and the train is rerouted so that one track worker is killed, but the other five are saved). Such thought experiments are used to explore under what conditions and why people are making deontological or utilitarian decisions [4; 5]. Although numerous arguments can be found for both choices, there is cross-cultural agreement to save more lives, to prefer the lives of younger people, and to prefer a human life over an animal [4]. The deontological-utilitarian distinction is a heavily researched area in moral psychology that provides insights into how people think morally. There is also evidence that while people are more likely to trust deontological judges and perceive them as more social, they attribute more competence to utilitarian judges [6; 7]. Does this suggest that moral experts should always advise the utilitarian decision? Arguably, this depends heavily on the dilemma itself, as well as the philosophical tradition within which it is being argued.

Other methods of evaluating moral judgments prioritize identifying and eliminating detrimental influences during the decision-making process, rather than focusing on the actual outcome of the decision. If moral experts are more resistant to undesirable influences than lay people, this would be an indication of moral expertise. For example, if there were several moral decisions to be made, the order in which the moral problems are presented should not influence the decisions. In an admittedly small study with 50 German students, psychologists Alex Wiegmann, Yasmina Okan, and Jonas Nagel [8] indeed observed an order effect for some dilemmas. To be able to answer whether such an order effect also occurs among potential moral experts, philosopher Eric Schwitzgebel and psychologist Fiery Cushman [9] compared the answers of 324 philosophers with the answers of another 753 academics and 1,389 non-academics. Participants were presented with 17 dilemmas in different orders.

The results of the study showed that the philosophers (among them also many with ethics as a focus) were also influenced by the presentation order of the dilemmas. Philosophers thus seem to be subject to very similar judgment biases as laypersons. On the one hand, these results could mean that philosophers do not automatically qualify as moral experts by virtue of their education, or that experts – just like laypersons – are not flawless [see also 10]. Thus, even this approach does not provide complete certainty about the existence of moral experts on the basis of their decision-making quality.

Fig 3: Is moral expertise a question of theory and knowledge?

Fig 3: Is moral expertise a question of theory and knowledge?

Moral expertise: a question of qualification?

Rather than defining moral expertise in terms of the decision made or the process of decision-making, alternative approaches focus on the expert as a person and their characteristics such as formal qualifications. One professional group that is often consulted on morality questions is philosophers. For example, the questions in the American column "The Ethicist" and in the Austrian radio program "Eine Frage der Moral" are answered by philosophers. Likewise, philosophers are often recruited for studies on moral expertise, which is why the qualifications of this group should be considered in more detail. The assumption that philosophers could be moral experts is supported, among other things, by the content of philosophy studies, in which ethical and moral theories are also taught. Logic, that is, logical thinking, which is helpful for complex moral decisions, is also part of the philosophy curriculum. In principle, philosophers would have expertise in moral principles, as well as the reasoning and argumentation skills needed, and could identify logical fallacies [11].

In a recent study, Eric Schwitzgebel, Bradford Cokelet and Peter Singer [12] were able to show that addressing the ethical reprehensibility of eating meat as an experimental intervention led to a reduction in meat consumption. In order to be able to analyze the actual meat consumption of the student participants, the purchasing behavior of the participants in the cafeteria was recorded a few weeks before and a few weeks after the experiment. Before addressing the ethical reprehensibility of eating meat, 52% of the meals purchased contained meat; after the intervention, this was reduced to 45%. Such a difference was not observed in a control group, in which only general charity and not the ethics of meat consumption were addressed as an intervention (52% meat-containing meals before and after the control intervention). Thus, this study provides evidence that philosophical or ethical theory knowledge may well lead to more ethical behavior [12]. However, it remains open whether behavior is changed in the long term because other studies showed that philosophy professors do not behave more ethically than other academics (with regard to meat consumption, organ donation, charity, honesty; [10].

Fig 4: Are philosophers moral experts?

Fig 4: Are philosophers moral experts?

It is interesting to note that the general population does not necessarily think of philosophers first when it comes to naming examples of moral experts: In a study of 50 U.S. respondents, religious persons were named most frequently (34%), followed by judges, politicians, or police officers (21%) and social workers (16%). Only 5% of the examples given referred to the professional group of philosophers [13]. Thus, for laypersons, theoretical knowledge that can be acquired through a philosophy degree does not seem to be exclusively relevant, but a person's actual lifestyle (religious, rule-following, helpful) could play at least as big a role in moral expertise. Perhaps this result also provides a clue as to why the moral expertise of Rainer Erlinger, the former author of the German newspaper column "Die Gewissensfrage" (The Question of Conscience) was recognized, even though he is not a philosopher, but a lawyer and physician.

Moral expertise: a question of virtue?

A person who lives according to moral principles, as stated by common expertise definitions, may well develop moral expertise if she receives feedback on her moral choices. When virtuous action becomes routine, it can become ingrained in a person's moral identity [14].

The fact that virtuous behavior is highly valued in the

field of moral expertise was also shown by another study with 203 US-Americans [13]. Participants were asked to rate the importance of certain traits for moral experts compared to experts from other, more easily defined fields (medicine, philosophy, science). The results showed that virtue was significantly more important for moral experts compared to all other areas of expertise. For example, a virtuous character here was associated with a moral compass, honesty,

conscientiousness, and life experience. In order to get to the bottom of an ideal percentage composition of knowledge-based qualification and virtuous character, almost 300 people were surveyed in a final study. For moral experts, a 40:60 ratio, that is, 40% formal qualification and 60% virtuous character, was indicated as the ideal mix. In comparison, for medical experts, participants indicated a 70:30 composition [13]. Accordingly, the results of the studies suggest that lay people expect moral experts not only to have knowledge about morality, but above all, to be moral. This is also relevant in the advice-giving function of moral experts because virtuous individuals are also more likely to be trusted [6] as well as perceived as sincere and likeable people [7].

Fig 5: Is moral expertise a matter of moral practice and virtue?

Fig 5: Is moral expertise a matter of moral practice and virtue?

Conclusion

Moral expertise is not easily defined on the basis of common expertise definitions because, on the one hand, the quality of decisions can hardly be measured objectively and, on the other hand, it remains unclear which expert characteristic (qualification or virtue) is decisive. The general population, however, seems to have a concrete and quite complex idea of moral expertise. A certain training in the sense of theoretical knowledge, education, and also intelligence is required. Additionally, virtuous behavior is also strongly included in the evaluation [13] because behavior allows conclusions to be drawn about a person's moral character [15].

Whether people seeking advice actually consider the qualifications and moral characters of potential advisors before seeking advice, or whether they blindly accept established moral expertise, remains to be seen. What is clear, however, is that experts who give us moral advice enjoy great popularity, even if they may not always be able to show us the longed-for, clear solution to a moral problem. But perhaps their advice opens up new perspectives on a problem, and thus helps us in our own decision-making.

Incidentally, in the case of the unpleasant colleague, Rainer Erlinger, the former moral expert of the Süddeutsche Zeitung, recommended helping them [2]. Whether the person seeking advice accepted the recommendation is unfortunately not known.

Bibliography

[1] Salas, E., Rosen, M. A., & DiazGranados, D. (2010). Expertise-based intuition and decision making in organizations. Journal of Management, 36(4), 941-973. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309350084

[2] Erlinger, R. (2015, 4. Mai). Mitleid für den Kotzbrocken? https://sz-magazin.sueddeutsche.de/die-gewissensfrage/mitleid-fuer-den-k...

[3] Foot, P. (1967). The problem of abortion and the doctrine of the double effect. Oxford Review, 5, 5–15.

[4] Awad, E., Dsouza, S., Kim, R., Schulz, J., Henrich, J., Shariff, A., … Rahwan, I. (2018). The moral machine experiment. Nature, 563(7729), 59–64. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0637-6

[5] Conway, P., Goldstein-Greenwood, J., Polacek, D., & Greene, J. D. (2018). Sacrificial utilitarian judgments do reflect concern for the greater good: Clarification via process dissociation and the judgments of philosophers. Cognition, 179, 241–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2018.04.018

[6] Everett, J. A. C., Pizarro, D. A., & Crockett, M. J. (2016). Inference of trustworthiness from intuitive moral judgments. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 145(6), 772–787. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000165

[7] Rom, S. C., Weiss, A., & Conway, P. (2017). Judging those who judge: Perceivers infer the roles of affect and cognition underpinning others’ moral dilemma responses. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 69(69), 44–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2016.09.007

[8] Wiegmann, A., Okan, Y., & Nagel, J. (2012). Order effects in moral judgment. Philosophical Psychology, 25(6), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2011.631995

[9] Schwitzgebel, E., & Cushman, F. (2012). Expertise in moral reasoning? Order effects on moral judgment in professional philosophers and non-philosophers. Mind and Language, 27(2), 135–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0017.2012.01438.x

[10] Schönegger, P., & Wagner, J. (2019). The moral behavior of ethics professors: A replication-extension in German-speaking countries. Philosophical Psychology, 32(4), 532–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2019.1587912

[11] Singer, P. (1972). Moral experts. Analysis, 32(4), 115–117. https://doi.org/10.1093/analys/32.4.115

From the editors

.