Nuances of Sexual Consent: Who? What? When? Where? Why? How?

People keep talking about sexual consent, but what is it? Let’s dive into some recent research and discover that there is more to sexual consent than you might think.

Sexual consent is nuanced. Internal consent feelings and external consent communication vary from person to person and context to context. This article breaks down several recent findings to demonstrate how there is more to sexual consent than people often acknowledge. I complement these findings with suggestions for future research that will deepen our knowledge of sexual consent. Finally, I encourage readers to continue thinking about sexual consent and discussing its many nuances with the people in their lives.

Sexual consent is not simple. It’s not the same as asking for a cup of tea [1]. It’s not fleeting like tapping “yes” on an app [2]. Sexual consent is fluid, complex, and nuanced.

People don’t even agree on what consent is. Is consent an agreement between two or more people? Is consent a feeling that what somebody is doing to you is okay? It seems pretty clear that consent isn’t the same as simply wanting something [3]. So, what is it?

Based on my research and informed by reviews of the academic literature, I define sexual consent as a person’s “voluntary, sober, and conscious willingness to engage in a particular sexual behavior with a particular person within a particular context” [4]. In this way, consent to sexual activity is a decision-making process that happens inside you. Think about your recent sexual experiences… How did you decide whether you were willing to do a certain behavior with another person? Typically, people associate their internal consent with feelings of readiness, safety, arousal, desire, and physical response [5].

However, people aren’t able to read each other’s minds, so it becomes important to express these feelings related to consent. Findings across studies suggest that people communicate sexual consent in various ways. Think once more about your recent sexual experiences… How did you know whether the other person felt ready, safe, aroused, desirous, and physically responsive? Maybe they said or did something. And perhaps some of their actions or words were clear while others were subtle. What about you…how did you let your sexual partner know that you were consenting?

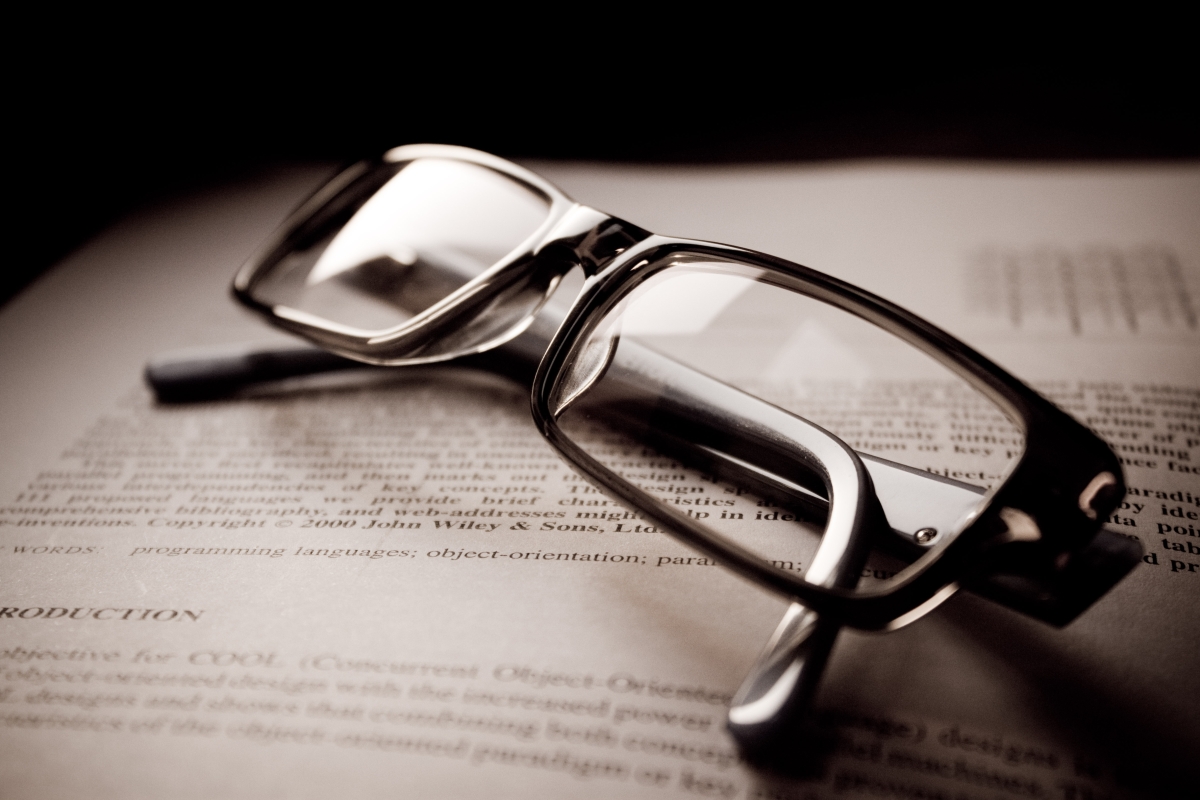

We know from research that people tend to be nonverbal when they let others know that they are willing to engage in sexual activity. The list of behaviors that can potentially indicate sexual consent is endless. Touching somebody’s arm. Undoing your bra or belt. Dimming the lights. Lifting your hips for somebody to remove your underwear. Or something as seemingly innocuous as taking off eyeglasses. Actions such as these can build on each other in an ongoing fashion to indicate that a sexual encounter continues to be consensual.

Verbal indicators of consent also come in many sorts. From the stilted “Do you want to have sex with me?” to the flavorful “Let me taste you,” there are several phrases people use to show that they are willing to engage in a sexual behavior. “Let’s go to my room.” “Is this okay?” “Will you go down on me?” “I’m ready when you are.” These examples of verbal cues and their translated equivalents are likely used by people all over the world, but partners might also develop their own euphemisms. To some, “Do you want to snuggle?” might simply refer to lying next to each other on the couch; however, others could use this gentler request to let their partner know that they are willing to engage in oral sex.

So, people can do or say things to communicate their consent. But is it possible to let somebody know that you are willing to engage in sexual activity by not doing anything? Some participants in research studies say that by not resisting sexual advances they are passively communicating their consent [6]. However, this approach to consent isn’t recommended, because doing nothing does not reliably reflect internal feelings of consent—which are more effectively revealed via actions or words [7].

To be clear, all of the behaviors and phrases I listed above do not necessarily indicate a person’s sexual consent. Certainly, there are times—indeed more often than not—that people take off their glasses without trying to communicate that they are sexually ready. But if somebody is alone with their partner, if they have been kissing, and if they don’t have anywhere to be, then the odds increase that taking off their glasses might mean they are willing to engage in increasingly intimate sexual behaviors. Context matters.

Let me remind you: sexual consent is a “voluntary, sober, and conscious willingness to engage in a particular sexual behavior with a particular person within a particular context.” Now, I will review findings from several studies that I have conducted to examine various nuances of sexual consent.

Recent Findings in Sexual Consent Research

Who are researchers talking about when they discuss sexual consent? My team and I reviewed academic articles on sexual consent to examine the types of participants that were used [7]. In sum, the articles in this review compiled sexual consent data from 12,295 participants across 41 unique samples. We found that, on average, participants in these studies were 20.5 years old. Further, 85.4% of the included samples consisted entirely of university students. Regarding racial identity, 79.3% of participants identified as White, 4.4% as Asian, 4.3% as Hispanic, 4.1% as Black, and 3.7% as another race. Therefore, everything I’ve said about sexual consent comes with a disclaimer: most of the data on this topic are drawn from White university students. While we didn’t compile data on sexual orientation, I know anecdotally that participants in previous studies on sexual consent were also predominantly heterosexual. Such lack of diversity across an entire body of work limits the conclusions and recommendations that can be made regarding how the general population experiences and communicates their willingness to engage in sexual activity.

What are people learning about sexual consent? To understand what people learn about sexual consent, I investigated several potential sources of consent education. In a content analysis of K–12 health education standards in the United States, my team and I found that sexual consent is rarely mentioned explicitly [8]. If students do learn about sexual consent in classrooms, it is likely done implicitly via topics such as communication skills, decision making, personal space, and interpersonal relationships. To assess informal forms of consent education, we also conducted media content analyses of popular movies and pornography [9,10]. These studies showed that examples of sexual consent communication in these media tend to be nonverbal or subtle. While there weren’t gender differences in consent cues modeled in movies, female characters in pornography were more likely than male characters to use subtle nonverbal cues and less likely to use clear verbal cues. Because these informal sources of consent education can also inform sexual behavior, people should be encouraged to actively engage with and critique the media they consume.

When do consent dynamics change in a sexual relationship? It likely won’t surprise you that sexual consent might look different for people on a first date versus people who have been friends with benefits for several months versus people who have been married for years. To assess how sexual consent changes over the course of a sexual relationship, my colleague and I conducted a daily diary study [4]. Each day for thirty days, participants reported whether they had engaged in sexual activity that day. On days that participants were sexually active, they reported whether they communicated their consent and how. If people were in a new sexual relationship, we found that they tended to rely exclusively on communication cues—whether verbal or nonverbal—to determine sexual consent. However, as people had more and more sex with their partner, they started assuming consent based on contextual cues, such as relationship status, routine, or emotions. This shift in the way people think about sexual consent seems to start shortly after the first time people engage in sexual activity but changes gradually. Even though consent dynamics can change over the course of a sexual relationship, a partner’s willingness should never be assumed or taken for granted.

Where does the process of sexual consent communication begin? Researchers have discussed sexual consent as an ongoing and step-by-step process—one that can begin as early as interactions in social settings. To test this theory, I wrote a story about a consensual sexual encounter between two fictional characters [11]. This story was chopped into eleven segments, and participants were only able to read one segment at a time. After each segment, participants were asked whether they thought the characters would be willing to engage in various sexual behaviors. We found that, as characters were depicted using more and more consent cues, the probability that people perceived them to be willing to engage in a sexual behavior increased. One of the biggest indicators of consent was the transition from a social to a private setting. Once the characters agreed to go home with each other from a bar, people were significantly more likely to think that the characters were consenting to sexual behavior—especially when male participants were asked to perceive the willingness of a female character who invited a male character home. People were further convinced that the characters were consenting once they moved from the living room to the bedroom. These findings suggest that people view sexual consent as a process that begins well before any sexual activity actually occurs.

Why do people consent to sexual activity that they don’t want? Sometimes people agree to sexual activity that they do not necessarily want. My team and I found that 2.5% of participants consented to unwanted sexual activity during their most recent sexual encounter [12]. The reasons people did this varied based on whether they had previously had sex with the other person. If they had been sexually compliant with an established sexual partner, people tended to say that they did so to please the other person or to stop their nagging. However, being drunk was the primary reason people identified for being sexually compliant with a person they had never had sex with before. On average, the top reason participants reported for being sexually compliant was that they felt pressured by the other person. As such, many of these experiences would indeed classify as sexual coercion. Consent education programs should emphasize that being drunk or being pressured, let alone being forced, can negate consent.

How drunk is too drunk? On that note, questions about sexual consent and alcohol consumption are seemingly ubiquitous. Data indicate that internal consent feelings tend to diminish with greater substance-related impairment—for example, at higher numbers of alcoholic drinks or when alcohol and cannabis are combined [13]. However, when we asked intoxicated people at a sporting event, 92.6% said they could consent to sexual activity, even though their average breath alcohol content level was high enough to be associated with lowered inhibitions as well as impaired judgment, coordination, and focus [14]. There likely will never be a clear-cut answer to this question, but research on how people conceptualize consensual versus nonconsensual substance-involved sexual activity may help clarify potential recommendations for best practice, education, and policy.

Future Directions for Sexual Consent Research

Who can we include in our samples? Researchers should increase the diversity of their samples. There are many individual differences that might influence sexual consent and its communication. For example, I am aware of several researchers who are investigating how sexual consent varies by sexual orientations, such as homosexuality, asexuality, and even digisexuality. How might two women or two men communicate their sexual consent? How do people navigate sexual consent when one of them universally lacks sexual desire? To what extent is sexual consent relevant when people have sex with robots? In addition to people’s sexual diversity, other individual differences that need to be considered and better represented in the science of sexual consent include age, gender identity, personality, ability, race/ethnicity, nationality, and socioeconomic status.

What can we do to teach people about sexual consent? Formal consent education tends to be limited to university student populations. Because most teenagers are engaging in sexual activity, consent education should begin much earlier. Otherwise, we are expecting young people to blindly navigate potentially complex social interactions. The many nuances of consent should be emphasized when crafting educational materials for classrooms. As such, a simple affirmative approach that defines sexual consent solely as an explicit and verbal “yes” will not suffice; students should instead be familiar with and able to use diverse active consent communication cues to infer whether another person is willing to engage in a behavior. Further, since there is evidence that movies and pornography might be sources of informal consent education, young people should also be taught media literacy skills to be able to critically reflect on the sexual interactions they see on their screens.

When do people use certain types of consent cues? Most existing research on sexual consent has focused on how consent communication varies between groups of people—comparing characteristics like gender or relationship status [15]. However, I recently demonstrated that people’s internal consent feelings and external consent communication are more likely to change from one sexual encounter to the next than they are to be stable [16]. For example, people’s communication of their willingness depends on the specific types of sexual behavior; they more actively communicate their consent to behaviors like oral sex or vaginal sex than they do behaviors like passionate kissing or genital touching. More evidence is needed to further understand when sexual consent might vary across other contexts.

Where else does the consent process exist? Most of the consent cues discussed in the academic literature are communicated face-to-face. However, with technologies emerging and interpersonal interactions evolving, consent communication likely takes place even when people are not right in front of each other. How is consent communicated on dating apps before people ever meet? Do people use GIFs or emojis to let others know that they are willing to engage in a sexual activity? The trend toward sexual behavior—and even the process of communicating sexual consent—occurring in virtual spaces may have only increased alongside extended periods of social distancing.

Why do people not consent to sexual activity they want? Opposite to sexual compliance, people can also want sexual activity but not consent to it. These motivations vary. Maybe the person is nervous. Maybe they don’t have access to their preferred contraceptives. Maybe they feel that they would be letting down their parents or religion. To better understand these nuances of sexual consent (or lack thereof), researchers should consider investigating people’s refusals when the sexual activity is wanted. Sexual consent and sexual refusal, which is an expression of unwillingness to engage sexual behavior with another person, are distinct but related experiences that should be considered in tandem for a more comprehensive understanding of consensual and nonconsensual sexual activity.

How can we learn more about sexual consent? Due to highly publicized legal cases (e.g., Brock Turner’s sexual assault; the Irish Rugby rape trial) and social movements on platforms like Twitter (e.g., #metoo; #thisisnotconsent), sexual consent stirs in the minds of people all over the world. According to Google Trends data, search interest for “sexual consent” has increased every year since 2004. People are eager to learn more about sexual consent, and researchers have responded.

Reflecting the public interest, studies on sexual consent are being conducted and published at increasingly higher rates. I encourage you to seek further scientific evidence on sexual consent. A good place to start would be Nuances of Sexual Consent [17], a book I edited that presents a collection of research studies that uncover intricacies related to how people experience, communicate, or perceive willingness to engage in sexual behavior with another person.

As you learn more, please discuss these nuances of sexual consent with those around you. Because people do not receive any official training on how to identify feelings of consent or how to communicate those feelings to others, you can be the one to provide them insight to the science of sexual consent.

Final Thoughts

Sexual consent is a complicated phenomenon, but that shouldn’t scare you. People are deft communicators when it comes to sex—easily discerning their partners’ subtle cues [18]. It’s amazing really. Even though a person’s willingness to engage in sexual behavior can be remarkably nuanced, most sex is consensual. But most isn’t enough. To prevent nonconsensual sex and promote healthy sexuality, the process of sexual consent must be ongoing and requires mutual respect between those involved.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to my colleagues who contributed to the studies cited in this article. I would also like to thank inMind for putting together this important special issue on sexuality and giving me the opportunity to contribute.

References

[1] Tea Consent. (2015). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oQbei5JGiT8

[2] LegalFling. (2018). Retrieved from https://legalfling.io/

[3] Peterson, Z. D., & Muehlenhard, C. L. (2007). Conceptualizing the “wantedness” of women’s consensual and nonconsensual sexual experiences: Implications for how women label their experiences with rape. Journal of Sex Research, 44(1), 72–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490709336794

[4] Willis, M., & Jozkowski, K. N. (2019). Sexual precedent’s effect on sexual consent communication. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(6), 1723–1734. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1348-7

[5] Jozkowski, K. N., Sanders, S., Peterson, Z. D., Dennis, B., & Reece, M. (2014). Consenting to sexual activity: The development and psychometric assessment of dual measures of consent. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(3), 437–450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0225-7

[6] Willis, M., Murray, K. N., & Jozkowski, K. N. (2021). Sexual consent in committed relationships: A mixed-method dyadic study. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 47(7), 669–686. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2021.1937417

[7] Willis, M., Blunt-Vinti, H. D., & Jozkowski, K. N. (2019). Associations between internal and external sexual consent in a diverse national sample of women. Personality and Individual Differences, 149, 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.05.029

[8] Willis, M., Jozkowski, K. N., & Read, J. (2019). Sexual consent in K–12 sex education: An analysis of current health education standards in the United States. Sex Education, 19(2), 226–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2018.1510769

[9] Jozkowski, K. N., Marcantonio, T. L., Rhoads, K. E., Canan, S., Hunt, M. E., & Willis, M. (2019). A content analysis of sexual consent and refusal communication in mainstream films. Journal of Sex Research, 56(6), 754–765. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2019.1595503

[10] Willis, M., Canan, S. N., Jozkowski, K. N., & Bridges, A. J. (2020). Sexual consent communication in best-selling pornography films: A content analysis. Journal of Sex Research, 57(1), 52–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2019.1655522

[11] Willis, M., & Jozkowski, K. N. (2022). Sexual consent perceptions of a fictional vignette: A latent growth curve model. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51,797–809. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02048-y

[12] Willis, M., Fu, T. C. J., Jozkowski, K. N., Dodge, B., & Herbenick, D. (2022). Associations between sexual precedent and sexual compliance: An event-level examination. Journal of American College Health, 70(1), 107–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2020.1726928

[13] Willis, M., Marcantonio, T. L., & Jozkowski, K. N. (2021). Internal and external sexual consent during events that involved alcohol, cannabis, or both. Sexual Health, 18, 260–268. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH21015

[14] Jozkowski, K. N., Marcantonio, T. L., Willis, M., & Drouin, M. (2022). Does alcohol consumption influence people’s perceptions of their own and a drinking partner’s ability to consent to sexual behavior in a non-sexualized drinking context?, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605221080149

[15] Willis, M., Hunt, M., Wodika, A., Rhodes, D. L., Goodman, J., & Jozkowski, K. N. (2019). Explicit verbal sexual consent communication: Effects of gender, relationship status, and type of sexual behavior. International Journal of Sexual Health, 31(1), 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2019.1565793

[16] Willis, M., Jozkowski, K. N., Bridges, A. J., Veilleux, J. C., & Davis, R. E. (2021). Assessing the within-person variability of internal and external sexual consent. Journal of Sex Research, 58(9), 1173–1183. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2021.1913567

[17] Willis, M. (Ed.). (2022). Nuances of sexual consent. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003276180

[18] Beres, M. (2010). Sexual miscommunication? Untangling assumptions about sexual communication between casual sex partners. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 12(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369105090307522