What career should I choose? How self-stereotyping can influence career decisions

Stereotypical self-characterizations of women and men can result in different career decisions – contributing to the continuing gender imbalance in leadership and many career fields. We explain how stereotypical self-characterizations develop and how they influence career decisions, behavior, and even performance. We give practical tips on how people themselves as well as organizations can minimize the influence of self-stereotyping to foster more equal gender distributions and career trajectories.

“We must reject not only the stereotypes that others have of us but also those we have of ourselves“, Shirley Chisholm, 1970, first African American woman elected to the United States Congress.

Men and women do not only hold stereotypical assumptions about others, but also describe themselves with stereotyped characteristics (like perceiving women in general to be more emotional or men in general to be more competitive). These stereotypical self-characterizations have important consequences for people’s decisions and behaviors – especially when related to their careers.

What is self-stereotyping?

When people are asked how they would describe themselves, they often have a well-defined image of themselves: Women describe themselves more than men with communal characteristics – that is, characteristics related to relationship-building and maintenance like being supportive, understanding, or emotional[1]. Men describe themselves more than women with agentic characteristics – that is, characteristics related to leadership- and performance-orientation like being dominant, assertive, or competent. These differences in self-characterizations are grounded in gender stereotypes as they parallel how men and women are viewed in a society[1],[2],[3]. The internalization of stereotyped characteristics into one’s personal identity (one’s self-view) is referred to as self-stereotyping[4].

Self-stereotyping is relevant especially in the work context, because people tend to behave in line with their self-views, for example, when deciding which career to pursue. Thus, stereotypical self-characterizations affect men’s and women’s life and career decisions differently[5]. Amongst other influencing factors (like gender stereotyping of and biases towards applicants), such career decisions are co-responsible for the continuing imbalance between men’s and women’s careers: The unequal distribution of women and men in different work fields (horizontal gender segregation) and the higher representation of men in leadership positions and other positions of power (hierarchical gender segregation)[6].

How do stereotypical self-characterizations develop?

Men and women sometimes appear to act differently. It is often argued that the difference in behavior between genders is due to biological differences and therefore immutable[7]. An example that is often given is that small children are interested in different games and toys. Although there are differences in the brain and brain activity of women and men[8], today many scientists believe that notwithstanding a biological basis, gender differences and self-characterizations are to a large extent socially constructed[9]. For example, a study showed that at the age of 12 months, boys do not prefer cars and girls do not prefer dolls, but gender preferences developed by 18 months of age[10]. Similarly, there are no gender differences in communal and agentic behavior in children of 13 to 14 months[11]. Adults, however, reinforce and reward stereotype-consistent behavior, that is, agentic behavior in boys and modest communication behavior in girls. Only 11 months later children have learned which modes of behavior are most appreciated and promising for them. From this age on, boys act more agentic than girls and girls communicate more with kindergarten teachers than boys.

Information regarding stereotypical characteristics are omnipresent and reinforce stereotypical images. There are many initiatives that aim to reduce stereotypes and the traditional gender roles they are grounded in, in order to foster gender equality, although some might argue that accomplishing this goal is still a long way off. Though there are considerably more women in gainful employment than a few decades ago, men and women still fulfill different social roles: Women typically work part-time more frequently and take over more household and family tasks, and men spend less time raising kids[12]. In many technical occupations and positions of power, women continue to be underrepresented; in many social occupations, men continue to be underrepresented.

It is still rare to see women in traditionally male roles such as construction workers or men in traditionally female roles such as kindergarten teachers. The observation of men and women in traditional roles contributes to the development of stereotypes and stereotypical self-characterizations.

Source: whitesession via pixabay (https://pixabay.com/de/photos/frau-bauhelm-werkzeug-bauarbeiter-2759503/, CC: https://pixabay.com/de/service/license/)

Children learn about gender roles and stereotypes by seeing men and women in distinct social roles[13]. They see more female kindergarten teachers and nurses and how women take over many communal, caring activities; they also see more male construction workers and computer scientists and how men take over many agentic, solution-oriented activities. Through these observations of different gender roles, children learn what men and women “are like”[14]. Through the observation of gender-role consistent behaviors of adults and other children, and the reactions of others to this behavior (see studies above: gender-conform behavior is reinforced and rewarded), children learn how men and women “ought to be”. As soon as children realize that they belong to one of the gender groups, they strive to be and act like others in this groups. Children, thereby, (unconsciously) incorporate typical characteristics of their respective gender group into their self-view.

How can self-stereotyping influence career decisions?

Self-stereotyping can strongly influence our behavior, usually without us noticing. There are many ways that self-stereotyping influences career decisions and behavior. We explain three important mechanisms: (1) lack of fit perceptions, (2) stereotype threat, and (3) backlash avoidance.

Lack of fit perceptions. When choosing a study area or profession, there is a strong self-selection: Men tend to opt for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics fields more than women. Women opt for social fields (e. g. education, nursing) more than men and are less likely to seek leadership positions. Why is that?

Heilman's lack of fit theory[5],[15] suggests that when making career decisions, men and women assess their fit to positions and occupational fields by evaluating to what extent their stereotypical self-characteristics match the perceived demands of the position or field. Via this comparison, women and men estimate (sometimes unconsciously) how good their performance might be in a given position or field. For example: Leadership positions are often perceived as strongly agentic, that is, leaders are perceived to be assertive, dominant, and competent in leadership[16]. If a woman who perceives herself as very communal but less agentic assesses to what extent her characteristics match the characteristics she perceives to be required for the leadership position, she might perceive little fit. She might conclude that she does not have the necessary skills for the position - even if that may actually not be the case (in addition, leadership positions actually also require many communal characteristics like being considerate of employees).

The perception of a lack of fit does not arise solely on the basis of perceived competences. An equally important aspect is people’s assessment of whether they would feel comfortable when working in a specific position or career field. In other words, women and men also evaluate their fit in terms of whether they would feel that they belong[17]. A felt sense of belonging is higher if people expect others in this position or field to be particularly similar to them.

Research also found that men and women endorse gender-stereotypic goals[18]: While women (often more than men) strive to fulfill goals related to communality like helping others, men (often more than women) strive to fulfill goals related to agency like status.

If people perceive a low fit because of a perceived lack of competence, because of a perceived lack of belongingness, or because of the perceived impossibility to attain personal goals, they are likely to make gender-stereotypic career choices. In other words, people decide for or against entering a career field depending on the perceived fit between their self- and career-characterizations. Some professions, such as engineer or soldier, are associated with agentic characteristics; other professions such as developmental psychologist or nurse are associated with communal characteristics. Because of their agentic and communal self-characterizations, men on average tend to perceive a fit with the first, and women with the second type of careers. For example, one reason for few women to choose science, technology, engineering, or technology careers is the belief that they would not offer the opportunity to fulfill communal goals[19]. In addition, childcare and education requires high levels of communality. Hence, men’s perceived lack of fit with communal roles can make it less likely that they opt for long periods of parental leave (besides other reasons like men’s often higher pay compared to women’s or fear to be viewed negatively by others).

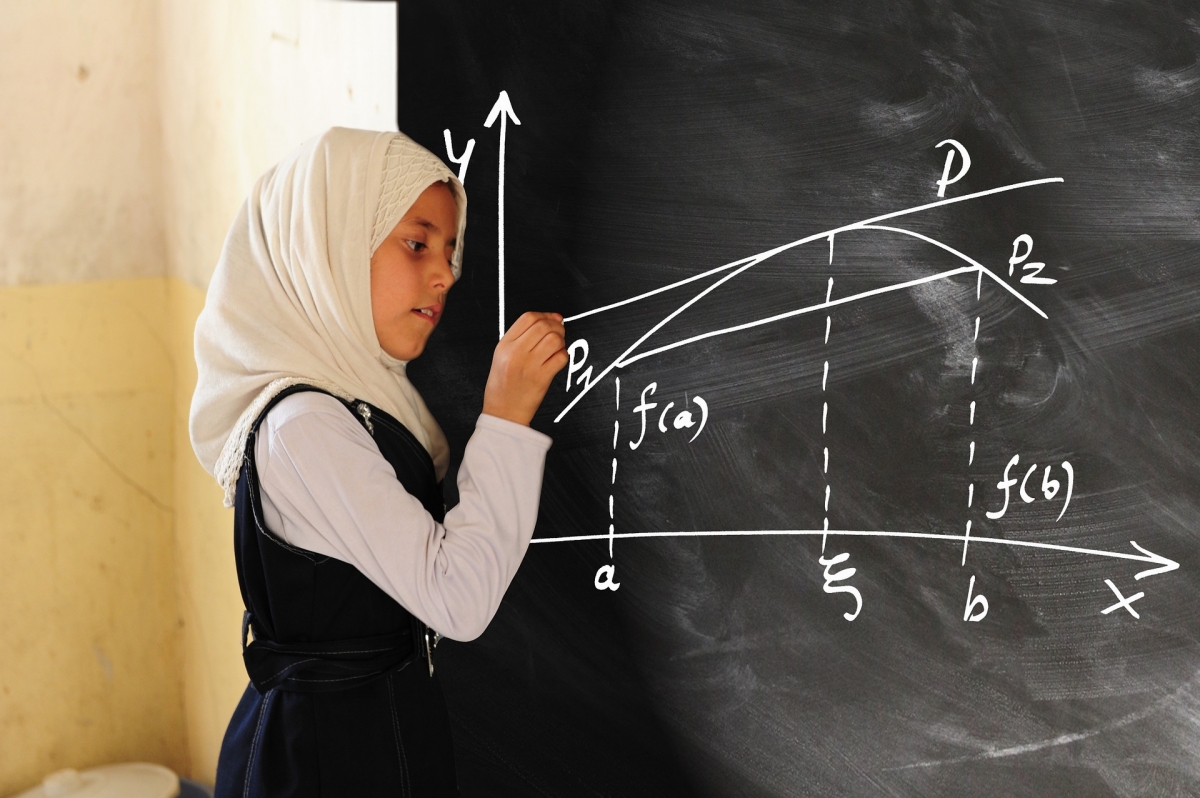

Stereotype threat can lead to lower math performance of girls and women.

Source: geralt via pixabay (https://pixabay.com/de/illustrations/m%C3%A4dchen-schule-tafel-mathemati..., CC: https://pixabay.com/de/service/license/)

Stereotype threat. Active gender stereotypes about skills and competencies (e.g., “Girls are not good in math and boys are not sensitive.”) can influence people’s performance and decisions[20]. An example: Women have internalized the stereotype that they are less competent in math compared to men and if this stereotype is activated in women, they indeed perform worse than men – they do not perform worse, however, if the math test is described as not producing gender differences[21]. Similar effects occur for men in situations that require emotional sensitivity[48]. Already very subtle stereotype signals can trigger stereotype threat effects: Female engineers perform worse after a conversation with sexist men[22] and women show lower ambitions to take on a leadership role after watching commercials in which traditional gender roles are portrayed[23].

Backlash-Avoidance-Model. Generally, women and men can predict relatively accurately, how others react to them if they show certain behaviors. If need be, they actively change their behavior to fulfill expectations for their gender. For example, when women self-promote extensively in a job interview, they are less liked than men showing the same behavior; and this lower liking negatively influences women’s chances of being hired[24]. The backlash-avoidance-model[25] proposes that women are aware of the risk of negative evaluations, which is why they purposefully refrain from high levels of self-promotion. In another study, women negotiated almost $8,000 salary a year less than men. The reason: They negotiated more modestly for fear of negative evaluations and social backlash[26].

What are career consequences of self-stereotyping?

Self-stereotyping affects career-relevant decisions. For example, self-stereotyping affects the jobs and tasks we choose, whether or not we prefer to work alone or in a team, and how we judge our work performance.

Which tasks do women and men choose? Women internalize stereotypes about a lack of competence compared to men in traditionally male-typed fields and sometimes have lower self-confidence in their own skills[27]. This is the reason why women sometimes choose less challenging work tasks when under performance pressure – challenging tasks, however, can positively affect career advancement[28].

When do people decide to work alone or in a team? Women tend to expect (subconsciously) to be less successful in managing traditionally masculine tasks (e.g., changing engine oil), while men tend to expect to be less successful in managing traditionally feminine tasks (e.g., decorating a shop window). On these stereotypically opposite- gender tasks, women and men tend to choose teamwork (rather than working alone); they hope to be more successful in the team than by themselves[29].

How do women judge teamwork contributions? When a man and a woman work together on a traditionally masculine tasks and get positive team feedback (e.g., “The team has done an excellent job!”), women have been found to ascribe the lion share of work and success to their male team partners and themselves accordingly less[30] (and outside evaluators have the same bias[31]). When women receive personal feedback on the same tasks (e.g., “You have done an excellent job!”), they evaluate their own contribution as equally important as the contributions of their partner.

Practical tips to minimize the influence of self-stereotyping

What can people themselves do?

- Self-reflection[32] (e. g. during coaching) can help men and women to become more aware of themselves: "What are my strengths?" Or "What strengths do others like colleagues or supervisors perceive in me?” A resulting more precise self-view may be less based on stereotypes and may lead to more accurately fit perceptions with occupations, positions, or tasks.

- Awareness that a first impression of an occupation, study area or job is not always correct can be helpful. Many traditionally masculine areas do not only require easily observable agentic characteristics but also less easily observable communal characteristics such as cooperation (and vice versa: traditionally feminine areas also require agency). It is worthwhile to obtain additional information in order to recognize various aspects of a career opportunity – which might enhance fit perceptions to fields traditionally occupied by the other gender.

- Mentoring and participation in competence or leadership trainings[33] are another way to reduce self-stereotyping and strengthen, for example, women's interest in leadership positions.

- Feedback-seeking and discussion of career goals with a supervisor[34] can help to make supervisors aware of a person’s career motivation and can animate the supervisor to give career support. It can also help people to identify which skills they need to develop. Thus, do not wait for the supervisor to discover your goals on their own but tell them where your interests lie and in which directions you want to develop as well as how they could potentially help.

Further, in salary and other negotiations, women face a double bind: If they do not bargain, they have to settle for low outcomes such as low salary; if they negotiate, they may be perceived as too demanding or not nice enough and people will want to work less with them[35]. However, agentic women are not evaluated negatively when agentic behavior is expected or seen as appropriate[36] – for example, when a leadership role requires it – or when they negotiate on behalf of others[26]. Furthermore, women benefit[37]…

- ...from clear negotiation rules and standards (which minimize ambiguity);

- ...from adapting their own negotiation behavior to match the behavior of the other negotiation party (e.g., their level of perseverance);

- ...when they make it clear in negotiations why their demands are legitimate

- ...if they temper agentic with communal behavior such as feminine charm[38]; (However, men who engage in small talk before negotiations – a communal behavior – benefit even more than women do for the same behavior[39].)

What can management and organizations do?

- Organizations can use targeted recruitment[40] and heighten the number of female applicants by approaching women on college campuses. This also increases the support for diversity in managers, who go on college visits[41].

- Organizations can offer workshops[42] on gender-fair recruitment and on gender stereotypes sensitization to their own employees, which can reduce the impact of self-stereotyping in organizations.

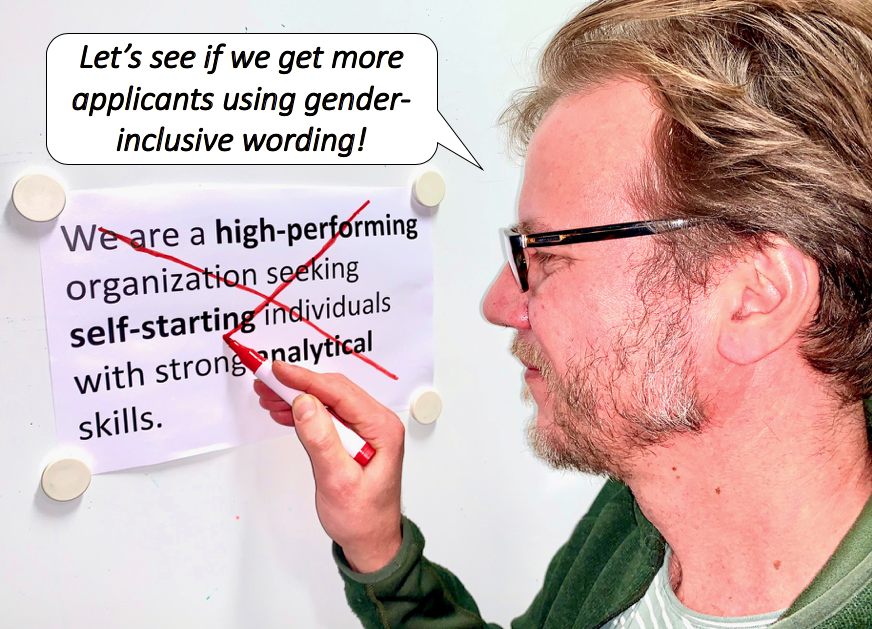

- Organizations can be aware of and adjust the wording of recruitment advertisements[43],[49]. Positions can be portrayed in a realistic way, while the amount of communal and agentic requirements and task descriptions is balanced whenever possible. Traditionally male-typed positions like management are often advertised predominantly with agentic terms (like “assertive” or “competitive”), although some of the most effective leadership behaviors are based on communality (e.g., employee development). When positions are advertised with more communal characteristics (like “cooperative”, “communicative”, or “team-oriented”), women show higher application intentions while application intentions for men are not affected.

Women’s perceived fit to leadership positions is influenced by word choice in job advertisements.

Source: Tanja Hentschel

- Organizations can also adjust linguistic forms and pictures in recruitment advertisements. Women indicate higher application intentions for traditionally masculine fields (e.g., entrepreneurship) when recruitment advertisements forego male-typed images and generic masculine word forms some languages offer (masculine linguistic form of "entrepreneur" used as a generic for men and women; e.g. German “Unternehmer”). Women’s application intentions can be enhanced if organizations use neutral or more female-typed images and gender-inclusive language forms ( gender-fair word pair of feminine and masculine linguistic forms "entrepreneur, fem./entrepreneur, masc.", e.g. German “Unternehmerin/Unternehmer”)[44].

- Managers should show individualized consideration to subordinates[45]. Managers are well advised to ask subordinates about their career goals and be supportive even if subordinates aim for a career path not in line with traditional gender roles. For example, managers should keep an open mind and be supportive if a high-achieving male subordinate wishes to take long parental leave or if a high-performing female subordinate with four children aims for a competitive leadership position. It is important to create a trusting environment[46], so that subordinates feel comfortable to be open about their goals and aims.

Conclusion

Self-stereotyping processes can have important effects on women’s and men’s career decisions. This article described why and when women and men may make gender-typed career decisions and how these contribute to gender imbalance both in occupations and on career levels.

It is crucial to note that the gender differences described here do not apply to every single woman or every single man. Despite the general societal trends, we discussed here, there are large individual differences in how women and men characterize themselves or behave[47]. In many cases, a man and a woman may actually be more similar to one another than two people of the same gender. Thus, an inference about a person’s characteristics based on their gender (e.g., “You are sensitive, because you are a woman”) is in many cases not accurate – it would be stereotyping and should be prevented. Individual women (and men) should not bear the sole responsibility to question or even change stereotypical self-characterizations and resulting stereotype-congruent behaviors; each and every one of us is encouraged to keep asking "Would I have evaluated a man (or woman) differently in this situation?".

References

[1] Hentschel, T., Heilman, M. E., & Peus, C. (2019). The multiple dimensions of gender stereotypes – A current look at men’s and women’s characterizations of others and themselves. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(11). doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00011

[2] Eagly, A. H., Nater, C., Miller, D. I., Kaufmann, M., & Sczesny, S. (2019). Gender stereotypes have changed: A cross-temporal meta-analysis of U.S. public opinion polls from 1946 to 2018. American Psychologist. doi: 10.1037/amp0000494

[3] Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 878-902. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.878

[4] Hardie, E. A., & McMurray, N. E. (1992). Self-stereotyping, sex role ideology, and menstrual attitudes: A social identity approach. Sex Roles, 27(1), 17-37. doi: 10.1007/BF00289652

[5] Heilman, M. E. (1983). Sex bias in work settings: The Lack of Fit model. Research in Organizational Behavior, 5, 269-298.

[6] European Commission. (2019). Report on equality between women and men in the EU. Retrieved July 26, 2019, from https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/aid_development_cooperation_fundamental_rights/annual_report_ge_2019_en.pdf

[7] Lueptow, L. B., Garovich-Szabo, L., & Lueptow, M. B. (2001). Social change and the persistence of sex typing: 1974–1997. Social Forces, 80(1), 1-36. doi: 10.1353/sof.2001.0077

[8] Kelly, S. J., Ostrowski, N. L., & Wilson, M. A. (1999). Gender differences in brain and behavior: Hormonal and neural bases. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 64(4), 655-664. doi: 10.1016/S0091-3057(99)00167-7

[9] Wood, W., & Eagly, A. H. (2012). Biosocial construction of sex differences and similarities in behavior. In J. M. Olson & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 46, pp. 55-123): Academic Press.

[10] Serbin, L. A., Poulin-Dubois, D., Colburne, K. A., Sen, M. G., & Eichstedt, J. A. (2001). Gender stereotyping in infancy: Visual preferences for and knowledge of gender-stereotyped toys in the second year. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 25(1), 7-15. doi: 10.1080/01650250042000078

[11] Fagot, B. I., Hagan, R., Leinbach, M. D., & Kronsberg, S. (1985). Differential reactions to assertive and communicative acts of toddler boys and girls. Child Development, 56(6), 1499-1505. doi: 10.2307/1130468

[12] Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2016). American Time Use Survey. Retrieved September 8, 2016, from www.bls.gov/tus/charts/household.htm

[13] Eagly, A. H., & Steffen, V. J. (1984). Gender stereotypes stem from the distribution of women and men into social roles. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(4), 735-754. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.46.4.735

[14] Martin, C. L., & Ruble, D. (2004). Children's search for gender cues: Cognitive perspectives on gender development. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13(2), 67-70. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00276.x

[15] Heilman, M. E. (2012). Gender stereotypes and workplace bias. Research in Organizational Behavior, 32(0), 113-135. doi: 10.1016/j.riob.2012.11.003

[16] Powell, G. N., & Butterfield, D. A. (2015). Correspondence between self- and good-manager descriptions: examining stability and change over four decades. Journal of Management, 41(6), 1745-1773. doi: 10.1177/0149206312463939

[17] Cheryan, S., Plaut, V. C., Davies, P. G., & Steele, C. M. (2009). Ambient belonging: how stereotypical cues impact gender participation in computer science. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(6), 1045-1060. doi: 10.1037/a0016239

[18] Evans, C. D., & Diekman, A. B. (2009). On motivated role selection: Gender beliefs, distant goals, and career interest. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33(2), 235-249. doi: doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2009.01493.x

[19] Diekman, A. B., Brown, E. R., Johnston, A. M., & Clark, E. K. (2010). Seeking congruity between goals and roles: A new look at why women opt out of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics careers. Psychological Science, 21(8), 1051-1057. doi: 10.1177/0956797610377342

[20] Roberson, L., & Kulik, C. T. (2007). Stereotype threat at work. Academy of Management Perspectives, 21(2), 24-40. doi: 10.5465/amp.2007.25356510

[21] Spencer, S. J., Steele, C. M., & Quinn, D. M. (1999). Stereotype threat and women's math performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35(1), 4-28. doi: 10.1006/jesp.1998.1373

[22] Logel, C., Walton, G. M., Spencer, S. J., Iserman, E. C., von Hippel, W., & Bell, A. E. (2009). Interacting with sexist men triggers social identity threat among female engineers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(6), 1089-1103. doi: 10.1037/a0015703

[23] Davies, P. G., Spencer, S. J., & Steele, C. M. (2005). Clearing the air: Identity safety moderates the effects of stereotype threat on women's leadership aspirations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(2), 276-287. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.2.276

[24] Rudman, L. A., & Phelan, J. E. (2008). Backlash effects for disconfirming gender stereotypes in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 28, 61-79. doi: 10.1016/j.riob.2008.04.003

[25] Moss-Racusin, C. A., & Rudman, L. A. (2010). Disruptions in women's self-promotion: The backlash avoidance model. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 34(2), 186-202. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2010.01561.x

[26] Amanatullah, E. T., & Morris, M. W. (2010). Negotiating gender roles: gender differences in assertive negotiating are mediated by women's fear of backlash and attenuated when negotiating on behalf of others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(2), 256-267. doi: 10.1037/a0017094

[27] McMahan, I. D. (1982). Expectancy of success on sex-linked tasks. Sex Roles, 8(9), 949-958. doi: 10.1007/bf00290019

[28] De Pater, I. E., Van Vianen, A. E. M., Fischer, A. H., & Van Ginkel, W. P. (2009). Challenging experiences: gender differences in task choice. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 24(1), 4-28. doi: doi:10.1108/02683940910922519

[29] Vancouver, J. B., & Ilgen, D. R. (1989). Effects of interpersonal orientation and the sex-type of the task on choosing to work alone or in groups. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74(6), 927-934. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.74.6.927

[30] Haynes, M. C., & Heilman, M. E. (2013). It had to be you (not me)!: Women’s attributional rationalization of their contribution to successful joint work outcomes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(7), 956-969. doi: 10.1177/0146167213486358

[31] Heilman, M. E., & Haynes, M. C. (2005). No credit where credit is due: Attributional rationalization of women's success in male-female teams. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(5), 905-916. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.90.5.905

[32] DeRue, D. S., Nahrgang, J. D., Hollenbeck, J. R., & Workman, K. (2012). A quasi-experimental study of after-event reviews and leadership development. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(5), 997-1015. doi: 10.1037/a0028244

[33] Knipfer, K., Shaughnessy, B. A., Hentschel, T., & Schmid, E. (2017). Unlocking women's leadership potential: A curricular example for developing female leaders in academia. Journal of Management Education, 41(2), 272-302. doi: 10.1177/1052562916673863

[34] van der Rijt, J., Van den Bossche, P., van de Wiel, M. W. J., Segers, M. S. R., & Gijselaers, W. H. (2012). The role of individual and organizational characteristics in feedback seeking behaviour in the initial career stage. Human Resource Development International, 15(3), 283-301. doi: 10.1080/13678868.2012.689216

[35] Bowles, H. R., Babcock, L., & Lai, L. (2007). Social incentives for gender differences in the propensity to initiate negotiations: Sometimes it does hurt to ask. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 103(1), 84-103. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.09.001

[36] Hentschel, T., Braun, S., Peus, C., & Frey, D. (2018). The communality-bonus effect for male transformational leaders – leadership style, gender, and promotability. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 27(1), 112-125. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2017.1402759

[37] Bowles, H. R. (2013). Psychological perspectives on gender in negotiation. In M. Ryan & N. R. Branscombe (Eds.), The Sage handbook of gender and psychology (pp. 465-483). London, UK: Sage.

[38] Kray, L. J., Locke, C. C., & Van Zant, A. B. (2012). Feminine charm: An experimental analysis of its costs and benefits in negotiations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(10), 1343-1357. doi: 10.1177/0146167212453074

[39] Shaughnessy, B. A., Mislin, A. A., & Hentschel, T. (2015). Should he chitchat? The benefits of small talk for male versus female negotiators. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 37(2), 105-117. doi: 10.1080/01973533.2014.999074

[40] Digh, P. (1999). Getting people in the pool: Diversity recruitment that works. HR Magazine, 44(10), 94-98.

[41] Dobbin, F., & Kalev, A. (2016). Why diversity programs fail. Harvard Business Review, July-August 2016 Issue, 52-60.

[42] Sekaquaptewa, D. (2019). An evidence-based faculty recruitment workshop influences departmental hiring practice perceptions among university faculty. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 38(2), 188-210. doi: 10.1108/EDI-11-2018-0215

[43] Horvath, L. K. (2015). Gender-fair language in the context of recruiting and evaluating leaders. In I. M. Welpe, P. Brosi, L. Ritzenhöfer & T. Schwarzmüller (Eds.), Auswahl und Beurteilung von Frauen und Männern als Führungskräfte in der Wirtschaft – Herausforderungen, Chancen und Lösungen (pp. 263-272). Freiburg, Germany: Haufe.

[44] Hentschel, T., Horvath, L. K., Peus, C., & Sczesny, S. (2018). Kick-starting female careers - Attracting women to entrepreneurship programs. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 17(4), 193-203. doi: 10.1027/1866-5888/a000209

[45] Vincent-Höper, S., Muser, C., & Janneck, M. (2012). Transformational leadership, work engagement, and occupational success. The Career Development International, 17(7), 663-682. doi: 10.1108/13620431211283805

[46] Edmondson, A. C., & Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 23-43. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091305

[47] Hyde, J. S. (2005). The gender similarities hypothesis. The American Psychologist, 60(6), 581-592. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.6.581

[48]Koenig, A. M., & Eagly, A. H. (2005). Stereotype threat in men on a test of social sensitivity. Sex Roles, 52(7), 489-496. doi:10.1007/s11199-005-3714-x

[49] Gaucher, D., Friesen, J., & Kay, A. C. (2011). Evidence that gendered wording in job advertisements exists and sustains gender inequality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(1), 109-128. doi:10.1037/a0022530