The Violence We Have Committed

Circle of Willis is a podcast series from Associate Professor and Clinical Psychologist Dr. James Coan. The podcast features interviews with many of today's top social scientists, journalists, authors, and more. In a recent special episode of Circle of Willis, Dr. Coan speaks with five developmental scientists about what may be happening to the children who are currently being separated from their parents as part of a policy to deter immigration and asylum seekers at the southern border to the United States. Dr. Coan offers some background to the problem, what science has to say about it, and a link to the podcast below.

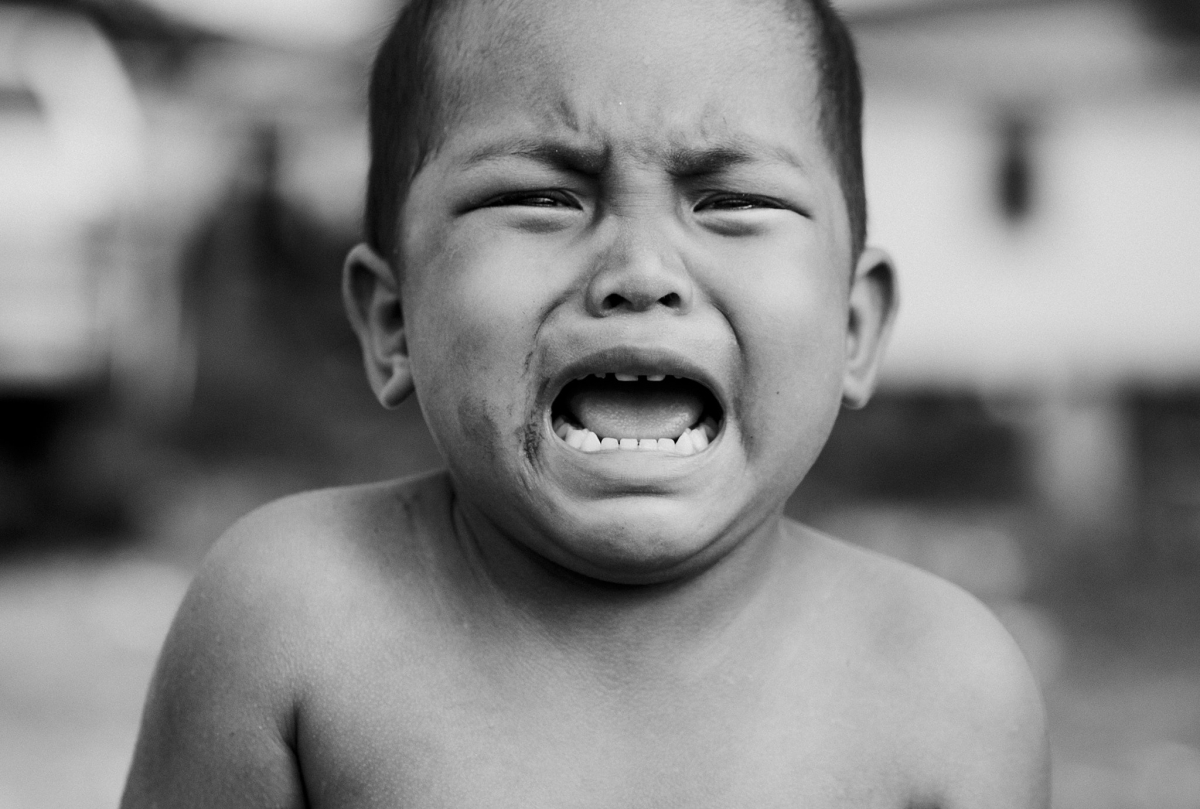

As many as 2,300 children have been affected by the 'zero-tolerance' immigration policy.

As many as 2,300 children have been affected by the 'zero-tolerance' immigration policy.

With its “zero-tolerance” policy toward individuals — including asylum petitioners — illegally crossing the southern border to the United States, the Trump administration has managed to transform a fictional immigration problem designed to whip up populist paranoia into a bona fide humanitarian crisis.

Because US law prohibits children from being prosecuted with their parents, the Justice Department (and President Trump, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and the US Border Patrol, and the Department of Homeland Security) have each claimed to have no choice but to transport any children ensnared by this policy to separate agencies and facilities, pending judgements as to the criminal liability or asylum status of their parents.

To achieve this, children have sometimes literally been forced from their parents arms. And upon separation, many of those children have been taken far away to detention centers scattered throughout the US without their parents’ knowledge.

Evidence is accumulating that some of these parents have been sent back to their home countries before being reunited with their children, that staff at detention facilities are overwhelmed and incapable of meeting the basic needs of those in their care, that some children have been forced or coerced into consuming psychotropic medications (including addictive anxiolytics), and that the agencies responsible for separating children from their parents have been so lax in their bookkeeping that a sizable number of children may actually never see their parents again.

More recently, President Trump issued an executive order to force law enforcement agencies at the border to keep families together. While this is a welcome development, it didn’t come fast enough to keep roughly 2,300 children — all younger than 12 — from being victimized. Moreover, the policy as it stands may simply cause children to be kept with their parents in adult incarceration facilities (a bizarrely welcome change, relatively speaking, but appalling nonetheless).

So here we are, with thousands of traumatized children and parents, many of whom are likely to have faced earlier traumas in their home countries as well as during their journey to the US.

Podcast episodes can be found at www.circleofwillispodcast.com. Image from James Coan.I’m a clinical psychologist by training, although I’ve never been licensed and now spend my time conducting research on the neural mechanisms linking social relationships to health and well- being. As just a regular human person, I responded with shock and horror to the scenes playing out in my country, but as a scientist used to thinking deeply about the vital necessity for health and happiness of proximity to those we know and love, something deeper stirred in me—an urgency to pound on the proverbial doors of my fellow citizens, shouting about the potential long term damage being done to these kids, to say nothing of their parents.

Podcast episodes can be found at www.circleofwillispodcast.com. Image from James Coan.I’m a clinical psychologist by training, although I’ve never been licensed and now spend my time conducting research on the neural mechanisms linking social relationships to health and well- being. As just a regular human person, I responded with shock and horror to the scenes playing out in my country, but as a scientist used to thinking deeply about the vital necessity for health and happiness of proximity to those we know and love, something deeper stirred in me—an urgency to pound on the proverbial doors of my fellow citizens, shouting about the potential long term damage being done to these kids, to say nothing of their parents.

I didn’t know exactly how to express this need, but instinct led me to talk with colleagues who know even more about this issue than I do—substantially more, it turns out. And because I was eyeing those “proverbial doors,” I wanted a way to share these conversations with the world. So I recorded them, and transformed them into a special episode (Children at the Border) of the science podcast I host called Circle of Willis.

I was exceedingly fortunate to have as my guests Jude Cassidy, Professor of Psychology and Distinguished Scholar-Teacher at the University of Maryland, Dylan Gee, Assistant Professor of Psychology at Yale University, Megan Gunnar, Regents Professor at the University of Minnesota, Charles Nelson, Professor of Pediatrics at Harvard Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital, and Nim Tottenham, Associate Professor of Psychology at Columbia University.

These scientists brought decades of combined scientific scholarship and expertise relevant to questions about the short and long term consequences the children trapped in this policy are likely to face. But they were also able to explain at a deep level why those consequences are likely — because they have studied the unique bonds between children and caregivers, the behavioral consequences of separation from those caregivers, the inadequacy of congregate care facilities such as those currently being deployed at our border, and how all of the above is manifest within the central and peripheral nervous systems.

What many Americans, not least border and immigration control agents, do not realize, is that for young children psychological trauma creates an increasingly well-defined pathway to brain trauma, which can alter behavior down the road in ways that lead to a lifetime of impaired health and even early death. For a proportion of children forcibly separated from their parents at the US border, real long-term harm has been done to their bodies. No less so—in the long run possibly more so—than if they were physically attacked.

So any notion that we have not done real violence to these children is an illusion. Indeed, the violence we have done is made all the more insidious because for most of us the scars are invisible to the naked eye. But the scientists I spoke to know exactly where those scars are, and how to find them. And for the scientists I interviewed, watching this avoidable, slow-motion catastrophe while knowing just how damaging it has been is its own form of torment.

Children at the Border makes for grim listening, but important listening, too. I hope you find it as useful as I have.