Empowerment instead of mind-control. Why myth-busting does not interfere with intellectual independence.

Reviewers: Annie Zhang and Ingrid Bachmann Cáceres

Editorial Assistant: Elena Benini

“Myth-busting is just policing thought!” “Fact-checkers tell us what to think!” These claims are common, but do they hold up? Ironically, while

myth-busting aims to foster critical thinking, it is often accused of shutting it down. This article examines why challenging

misinformation empowers rather than controls, and why

myth-busting strengthens, rather than weakens, intellectual independence.

Imagine this: You’re scrolling through social media. A friend shares a post accusing fact-checkers of acting like “thought police.” Someone else comments that myth-busting is just censorship in disguise. Maybe you’ve heard these claims before. Maybe you’ve even wondered: Who gets to decide what counts as a “myth”? Is myth-busting always fair or can it be one-sided? And does correcting misinformation really mean telling people what to think?

These are fair questions. No one wants to be manipulated or have their independence undermined. But here’s the twist: when done well, myth-busting isn’t about shutting down debate. It sharpens it. It helps us spot weak arguments, ask better questions, and think more clearly. So, what exactly is myth-busting – and why does it matter? Let’s find out.

Fig. 1 Educational Myths Debunked

Fig. 1 Educational Myths Debunked

1. What Myth-Busting Actually Is

Myth-busting means finding, examining, and challenging beliefs that are widely accepted but actually false or misleading. This involves strategies like prebunking, addressing myths before they spread [1], and debunking, which means correcting misinformation after it appears, often through fact-checking [2]. Both approaches aim to prevent false ideas from taking root and to promote more accurate understanding (see section 3). Myth-busting can be seen as a science, a craft, and an art. As a science, it is grounded, for instance, in cognitive and educational psychology and relies on theoretical and empirical research (e.g., [2]; [1]). As a craft, it involves developing and applying practical strategies and tools to refute myths effectively. As an art, myth-busting requires emotional competence, storytelling, and the ability to adapt communication to different audiences [3]. When combined, these aspects help ensure that myth-busting not only informs and corrects but also engages people and promotes lasting change.

Myth-busting can help strengthen several important competences and dispositions: It encourages critical thinking by teaching people to evaluate arguments and evidence [4]. It also supports intellectual independence by helping individuals form their own beliefs based on careful reasoning instead of simply following others [5]. Finally, myth-busting builds mental immunity, making it easier to resist the spread of misinformation and harmful ideas, sometimes called viruses of the mind [6].

Ideally, myth-busting is not about defending your opinions but about updating our beliefs based on new evidence. It encourages open, constructive discussions rather than avoiding conflict or starting arguments. In this way, myth-busting creates more room for honest conversation and new ideas. Therefore, myth-busting is crucial for maintaining a democratic, open society [7]. Tolerance (with boundaries) and open discussion are essential for intellectual growth and individual and societal progress.

Fig. 2 The Science, Craft, and, Art of Myth-busting

Fig. 2 The Science, Craft, and, Art of Myth-busting

2. What Myth-busting is NOT

Ironically, several myths about myth-busting exist. One persistent misunderstanding about myth-busting is the fear that it suppresses intellectual freedom. This concern stems from the misconception that debunking false or misleading claims limits open discussion. However, the opposite is actually true. Myth-busting helps conversations grow by ensuring they are based on solid evidence and careful thinking, rather than just on claims without proof.

Myth-busting is not censorship. It does not control what people are allowed to say or think [8]. Instead, fact-checking and myth-busting are forms of open, critical discussion that evaluate claims using evidence, not by silencing them. In fact, meta- analytic research shows that fact-checking is generally effective in reducing misinformation beliefs, even for people who are skeptical of fact-checkers [9].

Myth-busting is also not manipulation, indoctrination, or brainwashing. It is not about forcing anyone to adopt a certain belief or pushing an ideological agenda [10]. Instead, myth-busting aims to empower people by providing them with practical tools and strategies for critical thinking, such as heuristics, to identify myths or frameworks for evaluating claims (see section 3; [2], [11]).

Finally, myth-busting is not an attack on freedom of thought or speech. If anything, it supports intellectual independence. Saying ”I’m entitled to my opinion” does not mean that the opinion is automatically correct or that others must accept it. Healthy discussions and debates require strong evidence and sound reasoning, not just unsupported beliefs or the idea that everyone can believe whatever they want without proof.

3. Why Busting Myths Matters for (Sustainability) Education

Myth-busting matters not just in politics or media, but also in education, where it can seriously undermine effective, evidence-based practice and harm a wide range of people involved. Myths like “Everyone has a unique learning style” may sound plausible but misguide teaching and limit learning. Challenging such beliefs with evidence is just as crucial here as anywhere else. When teachers base their lessons on ideas that simply aren’t true, everyone loses. Time and energy get spent on strategies that don’t help —and sometimes even harm—students’ ability to learn. Instead of building knowledge and confidence, these approaches can leave students confused or frustrated. Over time, this doesn’t just slow down progress in the classroom. It also chips away at the trust that students and parents place in educators and makes it harder for evidence-based methods to take root [14], [15]. To understand why myth-busting matters in education, it helps to look at a concrete example that is both timely and consequential: sustainability education. This field has become increasingly prominent in schools and universities, yet it is also surrounded by persistent misconceptions. Take these examples: “Sustainability education is just environmental education”, “Its goal is to turn students into eco-activists”, or “Sustainability education alone will save the planet”. While such claims may sound plausible or even appealing, they oversimplify the complexity of the field and misrepresent its purpose.

So, what is sustainability education – clearly and simply? It’s about helping people develop the knowledge, skills, and attitudes to make informed and responsible choices that support ecological integrity, social equity, and economic viability. It’s not about prescribing values or pushing activism, and it’s not just about learning facts. At its core, it promotes critical thinking, plural perspectives, and responsible action – at home, at work, and in society at large [16].

To tackle educational myths, projects like MYTHSE (Identifying, Understanding, and Challenging Myths in and about Sustainability Education) investigate where common myths come from, why they persist, and how they can be effectively addressed [16]. This project combines research reviews, podcast-based interviews with experts, and practical tools to help teachers and students identify and rethink myths about sustainability, thereby building mental immunity [6].

4. How to Bust Myths: Practical Strategies

We are not helpless when it comes to myths in education. With the right strategies and tools, educators and learners can identify, question, and effectively counter false or misleading beliefs.

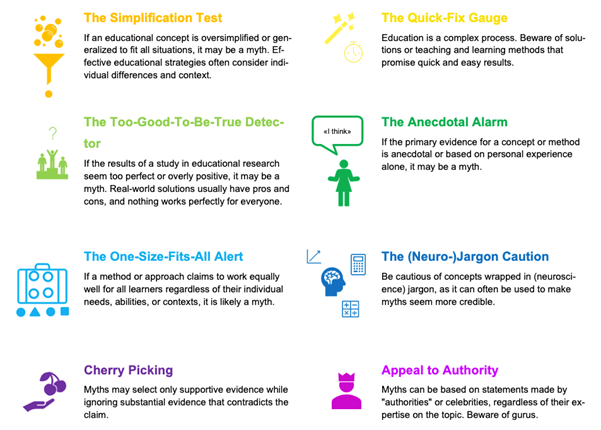

Identifying Myths with Heuristics: Some simple rules of thumb (see Fig. 4 below) can help people detect misleading claims early on. Common warning signs include emotionally charged language, cherry-picked evidence, and oversimplified arguments. Take the myth: “If students don’t learn something in childhood, they’ll never catch up later—the science is clear!” This claim raises red flags: it uses emotional exaggeration (“never catch up”), oversimplifies complex developmental processes, and selectively appeals to “science” without context [11]. Figure 4 shows some core strategies for identifying (educational) myths.

Fg. 4 Heuristics for Identifying Educational Myths

Fg. 4 Heuristics for Identifying Educational Myths

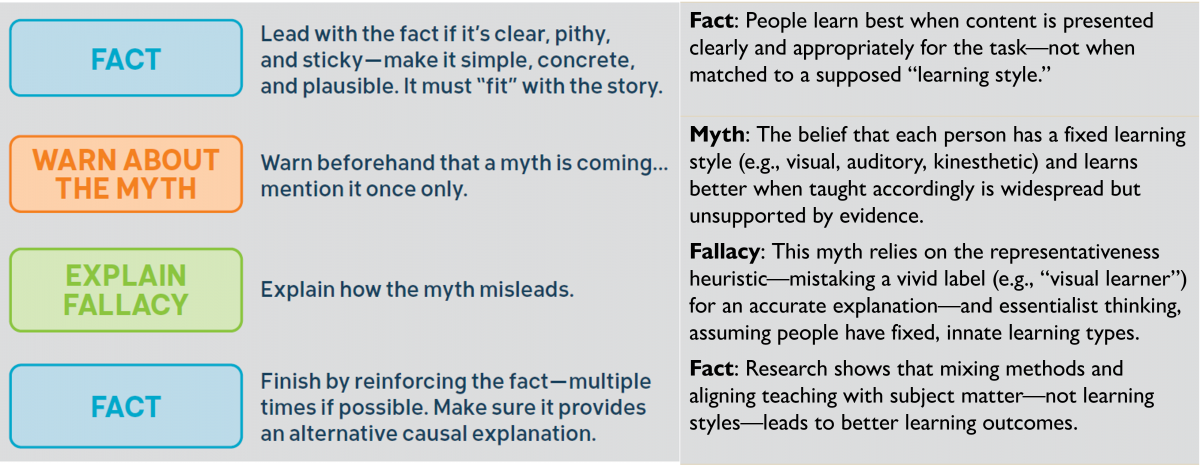

Debunking with Refutations: When a myth is already widespread, a simple correction isn’t enough. Research shows that refutations, structured responses that not only correct but also explain, are far more effective. One proven strategy is the truth sandwich: start with a clear, accurate statement (truth), then briefly address and explain the myth ( myth), and finally reinforce the accurate information (truth again). This structure helps prevent the myth from being accidentally reinforced and increases the chance that the correction sticks [11].

Fig. 5 Fact-Myth-Fallacy-Fact-Structure of Debunking aka Truth Sandwich

Fig. 5 Fact-Myth-Fallacy-Fact-Structure of Debunking aka Truth Sandwich

5. Why People Still Resist Myth-busting

Myth-busting is sometimes resisted not because of what it does, but because of how it’s perceived: Some see myth-busting as prescriptive, as if it aims to dictate beliefs (see section 2), rather than an invitation to think critically. This confusion arises when people mix up having a discussion (argumentation) with imposing ideas on someone (imposition).

When people feel their long-held beliefs or autonomy are under threat, they may experience reactance [12]. If people feel they are being corrected or told they are wrong, they may instinctively resist in (e.g., ignorance, rejection, abeyance) rather than reconsider their position [13]. Effective myth-busting should accordingly prioritize dialogue rather than confrontation. Encouraging constructive skepticism and making space for genuine questions helps reduce resistance. Ultimately, the goal is not to "win" an argument, but to create the conditions for better thinking.

6. Final Thoughts: Why Myth-Busting Supports Intellectual Independence

Myth-busting isn’t about telling people what to think. It’s about creating space for better thinking. When done well, it helps us distinguish fact from fiction, encourages open dialogue, and strengthens intellectual independence. But this isn’t always easy. Some myths are tied to identity or emotion, and attempts to correct them can trigger defensiveness, especially if the correction feels patronizing or politically loaded.

Poorly handled myth-busting, like that of self-appointed “debunkers” on social media who ridicule rather than engage, can backfire. It may reinforce mistrust instead of reducing it. That’s why effective myth-busting must prioritize respectful conversation over confrontation, curiosity over correction, and understanding over winning an argument.

Have you ever tried challenging a popular myth and met resistance? What made the conversation productive (or not)? And how can we foster a culture of myth-busting in (sustainability) education that invites reflection rather than shuts it down?

These are not rhetorical questions. Take them seriously and take them to your classroom, your team meetings, or your next conversation with a skeptical friend. That’s where meaningful, evidence-informed change begins.

Bibliography

[1] S. van der Linden, "Countering

misinformation through psychological inoculation" in Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol., vol. 68, pp. 1–60, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aesp.2023.11.001.

[2] S. Lewandowsky, J. Cook, U. K. H. Ecker, et al.,

Debunking Handbook 2020, 2020. https://doi.org/10.17910/b7.1182

[3] S. T. Siegel, "The science, craft, and art of mythbusting," Journal Trends und Themen aus der Wissenschaftskommunikation, 2024b. [Online]. Available: https://www.wissenschaftskommunikation.de/the-science-craft-and-art-of-m...

[4] J. Haber, Critical Thinking. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 2020.

[5] K. Shephard, Higher Education for Sustainability: Seeking Intellectual Independence in Aotearoa New Zealand. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature, 2020.

[6] A. Norman, L. Johnson, and S. Van Der Linden, "Do minds have immune systems?" J. Theor. Philos. Psychol., Apr. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1037/teo0000297

[7] K. R. Popper, The Open Society and Its Enemies. Princeton, NJ, USA: Princeton Univ. Press, 1963.

[8] E. Berkowitz, Dangerous Ideas: A Brief History of Censorship in the West, from Ancients to

Fake News. London, U.K.: Westbourne Press, 2021.

[9] N. Walter, J. Cohen, R. L. Holbert, and Y. Morag, "

Fact-checking: A

meta-analysis of what works and for whom" Political Commun., vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 350–375, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2019.1668894

[10] K. Taylor, Brainwashing: The Science of Thought Control. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford Univ. Press, 2006.

[11] S. T. Siegel, "Educational myths debunked," Lehrblick – ZHW Uni Regensburg, 2024a. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.5283/ZHW.20240215.EN

[12] B. D. Rosenberg and J. T. Siegel, "A 50-year review of psychological reactance theory: Do not read this article" Motiv. Sci., vol. 4, pp. 281–300, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000091

[13] C. A. Chinn and W. F. Brewer, "The role of anomalous data in knowledge acquisition: A theoretical framework and implications for science instruction," Rev. Educ. Res., vol. 63, no. 1, pp. 1–49, 1993, https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543063001001

[14] P. De Bruyckere, P. A. Kirschner, and C. Hulshof, More Urban Myths About Learning and Education: Challenging Eduquacks, Extraordinary Claims, and Alternative Facts. New York, NY, USA: Routledge, 2020.

[15] S. O. Lilienfeld, S. J. Lynn, J. Ruscio, and B. L. Beyerstein, 50 Great Myths of Popular Psychology: Shattering Widespread Misconceptions About Human Behavior. Malden, MA, USA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

[16] S. T. Siegel, "The Myths in Sustainability Education Navigator: Development, Design, and Uses-Cases of An Evidence-informed, and Accessible SE-Mythology," in Nachhaltigkeit und Bildungsmedien, P. Bagoly-Simó, B. Juska-Bacher, E. Matthes, S. Schütze, and J. Van Wiele, Eds. Bad Heilbrunn, Germany: Klinkhardt, 2025, in press.

Figure Sources

Figure 1: Dr. Stefan T. Siegel

Figure 2: [Science](https://pixabay.com/de/photos/konzept-mann-papiere-person-planen-1868728/), [Art](https://unsplash.com/es/fotos/una-pintura-de-un-paisaje-urbano-con-mucho...) and [Craft](https://unsplash.com/de/fotos/mann-mit-hammer-beim-schmieden-auf-amboss-...). Collage: Dr. Stefan T. Siegel (Pexels/Pixabay, Unplash/Fabian Bächli, Unsplash/Malcolm Lightbody)

Figure 3: Pixabay; https://pixabay.com/photos/secret-shut-up-shh-whisper-5137228/

Figure 4: Dr. Stefan T. Siegel; https://osf.io/psf2k

Figure 5: Lewandowsky et al. (2020)