Breathe through the stress: Simple breathing techniques for staying calm under pressure

Reviewers: Maša Iskra & Nina Hartter.

Editorial Assistant: Maren Giersiepen.

Breathing is more than an automatic process - it is a powerful tool for managing stress and improving focus. This article explores how intentional breathing techniques can help you stay calm under pressure, supported by the latest research on their physiological and psychological benefits. Discover evidence-based breathing techniques to improve performance and emotional balance.

Stress is a familiar companion for many, especially before important conversations, high-stakes presentations, or in the face of accumulating daily hassles. Sleepless nights, racing thoughts, and an overwhelming sense of pressure can feel unavoidable. Yet, one of the most powerful tools for managing this stress is something we do more than 20,000 times a day and often without conscious awareness: breathing. Among all vital functions, respiration is unique in that it operates automatically yet can be deliberately regulated. Therefore, it offers a suitable starting point for interventions [1].

Fig 1: More than air: how breathing shapes stress

Fig 1: More than air: how breathing shapes stress

The importance of breathing in stress regulation

Breathing is more than just a life-sustaining process. It is a direct line to your nervous system. During acute stress, the autonomic nervous system triggers the so-called fight-or-flight response [2]: heart rate accelerates, muscles tense, and breathing becomes rapid, shallow, and more irregular. While adaptive in life-threatening situations, this physiological cascade can become maladaptive in everyday situations such as academic stress, work pressure, or social interactions. Additionally, over the long term, it might contribute to the manifestation, relapse, and maintenance of mental illnesses, with breathing patterns predicting, for example, a relapse in depressive symptoms even after years [3]. Here is a game changer: respiration is not only reactive to stress, but also regulatory for many functions, such as emotions. Unlike most autonomic functions, breathing can be intentionally modulated, providing a direct means of influencing emotional states and signaling safety to an aroused bodily system. Neurophysiological evidence indicates that breathing rhythms are tightly coupled with affective, physiological, and cognitive processes [4]. And the best part? You can use this connection to your advantage. By deliberately controlling your breathing, you can actively influence your emotional, bodily, and cognitive stress responses. This makes breathing an actionable gateway to reducing test anxiety and restoring mental clarity, even in moments of acute psychological pressure.

The science behind breathing techniques

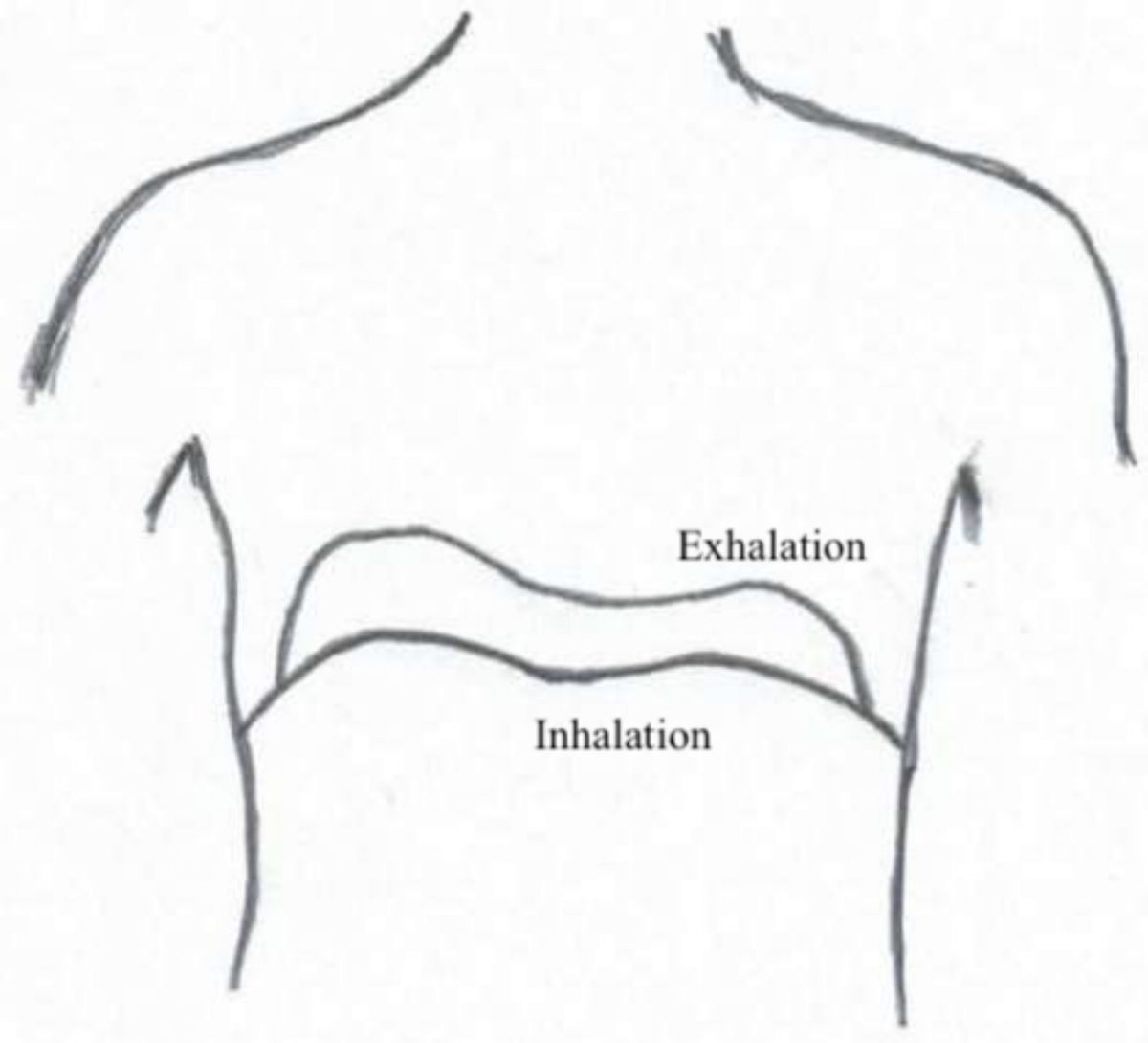

During the breathing cycle, inhalation is an active process in which mainly the diaphragm (the muscle below the lungs) and auxiliary respiratory muscles (such as the muscles between the ribs and at the side of the neck that help expand the chest) are involved. Exhaling, in contrast, happens naturally – it is a passive process in which these respiratory muscles relax.

Controlled, slower breathing engages the parasympathetic nervous system, the part of your body responsible for rest and recovery. One key pathway is the vagus nerve, which connects your brain to your heart, lungs, and digestive system. Controlled breathing patterns increase heart rate variability (HRV) through stimulation of the vagus nerve, which is a signal that your body is flexible and can adapt to stress more easily. This was shown to be a well-established marker of physiological flexibility and emotional regulation [5, 6]. Studies have demonstrated that deliberate breathing improves respiratory variability and modulates stress reactivity, particularly under conditions of worry [7, 8]. Like heart rate variability (HRV), respiratory variability reflects how well the body adapts to stress. In other words: deliberate breathing helps you breathe more flexibly, stay calmer when you feel worried, and return faster to regular slow breathing after stress. Diaphragmatic breathing, a type of intentional breathing (see exercises below), has been found to reduce negative affect and physiological arousal, while enhancing attention and cognitive control [9] – helping you to focus better, feel calmer, and think more clearly. A deep breath can feel grounding in the moment, but slow, rhythmic breathing over several minutes initiates deeper physiological effects, from reducing heart rate to calming neural circuits involved in stress. On a neural level, slow-paced and intentional breathing has been associated with increased functional connectivity between brain regions involved in top-down emotional regulation. Studies [10] emphasize that the simple act of returning to one’s breath can alter connectivity patterns between the prefrontal cortex and limbic structures, such as the amygdala, known to be involved in fear responses. This may help you to feel less anxious, think more focused, and better maintain control during stressful situations. Additionally, recent EEG (electroencephalogram) findings show that conscious connected breathing influences brain activity, helps regulate emotions, and increases awareness of internal bodily signals – a process known as interoception [11]. This enhanced awareness of bodily sensations may support one in recognizing early signs of stress and responding more adaptively during high-pressure situations.

These findings underscore the bidirectional relationship between breathing and the brain, positioning breathwork as a direct and scalable intervention for self-regulation and psychological resilience. Apart from being a valuable tool to reduce physiological stress and increase mindfulness, breathing techniques directly influence neural circuits, creating a pathway to improved emotional and mental well-being.

However, not all forms of breath control produce the same physiological effects. While simply becoming aware of one’s breath can already have a grounding effect, it is specifically slow, rhythmic breathing at a rate of around six to ten breaths per minute that has been shown to activate the parasympathetic nervous system [12]. This practice, known as resonance frequency breathing, promotes a state of cardiorespiratory coherence, where heart rate and respiration synchronize. Such synchronization supports autonomic balance and enhances emotional regulation. To take those findings into practice, the techniques described below focus on slow and relaxed breathing and breathing deeply into the abdomen [5, 6].

Easy breathing techniques for managing stress

Breathing techniques do not need to be complex to be effective. The key is to shift from shallow, erratic breathing to a slow, deliberate rhythm that signals safety to your body. Here are three simple techniques you can try the next time high pressure strikes – with brief notes on why each technique works.

Fig 2: Science-backed ways to breathe through stress

Fig 2: Science-backed ways to breathe through stress

1. Cyclic sighing

This technique involves a long inhale followed by a shorter, second inhale – a breathing pattern that mimics the body’s natural sigh reflex [13]. The second inhalation helps to maximize lung inflation and can support a more complete exhalation. Extended exhalation, in turn, is associated with increased parasympathetic activity and has been shown to reduce physiological arousal – a mechanism utilized in rescue breathing as well.

Instructions:

- Take a deep inhale through the nose

- Followed by a second shorter inhale to fully expand the lungs

- Slowly exhale through the mouth, fully emptying your lungs

- Continue this cycle for around 5 minutes to calm your nervous system

Rhythmic patterns of breathing help to calm and regulate your breathing and can bring a sense of balance and control.

2. Diaphragmatic breathing

Also called belly breathing, this method engages the diaphragm – the large muscle below your lungs [14]. When you breathe in, the diaphragm contracts and moves downward. This creates more space in the chest and gently presses on the organs below, which sends calming signals to the brain through the vagus nerve. When this kind of deep breathing is done slowly, it helps activate the parasympathetic nervous system and lowers activation of your body during stress.

Fig 3: The diaphragm during inhalation and exhalation

Fig 3: The diaphragm during inhalation and exhalation

Instructions:

- Place one hand on your chest and the other on your abdomen

- Breathe deeply into your belly so that only your lower hand rises

- Exhale fully, feeling your abdomen fall

- Continue for 2–3 minutes

Once you are firm in your practice, you do not necessarily have to put your hands on your body.

3. Rescue breathing

This exercise is based on slow, steady breathing with brief pauses after each inhale and exhale [15]. Maintaining a calm breathing rhythm helps to stabilize carbon dioxide levels in the blood, which are essential for regulating the drive to breathe. Since hyperventilation, often triggered by stress or anxiety, can lead to an excessive loss of carbon dioxide and disrupt the body’s acid-base balance, practicing slow, deliberate breathing can help to counteract this effect. By supporting a more balanced breathing pattern, this exercise can reduce physiological arousal and prevent the cycle of symptoms commonly associated with hyperventilation, such as dizziness, muscle tension, and heightened anxiety.

Instructions:

- Inhale through your nose until your lungs feel filled up

- Hold your breath for a few seconds, as long as it is still manageable and feels pleasant

- Exhale passively slowly through your nose or mouth, until all the air has left your lungs

- Let your shoulders fall, letting go of any tension in this area

- Hold your breath again for a few seconds, as long as it is still manageable and feels pleasant

- Repeat for 2-3 or more minutes

Beyond its general physiological effects, this breathing pattern can be fine-tuned based on individual needs and situational demands. In practical use, individuals often benefit from experimenting with different emphases – for example, gently extending the pause after exhalation when aiming to reduce tension before a high-stakes situation. Practical experience suggests that this individualized focus can support self-regulation in acute stress situations. Depending on one’s current emotional state, emphasizing either the pause after inhalation or after exhalation may help to restore balance [15] – for instance, by gently increasing alertness in moments of mental fatigue through gentle, extended breath holding after inhalation, or by downregulating excessive nervous arousal before high-stakes situations via (prolonged) exhalation.

While sometimes a related technique is referred to as “box breathing” (with each breath and pause timed by the same fixed number of seconds), this present version of deliberate breathing is flexible and accessible in more situations, offering a simple way to downshift your nervous system.

Making it a habit

While these techniques work well in moments of acute stress, their benefits multiply when practiced regularly. Just 5–10 minutes a day can help improve mood and reduce physiological arousal, with some breathing styles such as cyclic sighing showing particularly strong effects in daily practice [15]. To integrate these practices into daily life, consider pairing them with consistent routines: as a mental reset during study or work breaks, to unwind after a long day, while commuting, e.g., while waiting for public transport, before demanding conversations, or as part of a digital detox in the evening. Recent studies also suggest that slow-paced breathing before bedtime can improve sleep quality by reducing cognitive arousal and facilitating parasympathetic activation [16]. These small rituals can help anchor the techniques in memory and make them easier to access in high-pressure situations.

Fig 4: Turning breathing exercises into a habit: small rituals, big impact

Fig 4: Turning breathing exercises into a habit: small rituals, big impact

Why it’s worth it

Importantly, the effectiveness of breathing techniques depends not only on the act of breathing itself, but on how it is performed. Techniques that emphasize slow, consistent rhythms and diaphragmatic movement are particularly beneficial. Simply instructing individuals to “take a deep breath” may not be sufficient, and in some cases, can even lead to increased tension or hyperventilation if not guided properly. This is why structured approaches are so valuable: they provide a replicable format that supports both psychological and physiological balance. For people navigating their daily stressors, this distinction matters. Understanding that it is not just about breathing more, but about breathing differently, can make the difference between temporary relief and a sustained shift toward resilience.

At last: Stress is a part of life, but it does not have to control you. Breathing exercises are free, accessible, and backed by science, making them an invaluable tool for anyone facing pressure, whether in the classroom, the workplace, or beyond. Next time you feel nervousness creeping in, take a moment to pause and breathe. You might be surprised at the difference it makes.

Bibliography

[1] R. Ley, "Breathing and the psychology of emotion, cognition, and behavior," in Behavioral and Psychological Approaches to Breathing Disorders, B. H. Timmons and R. Ley, Eds. New York, NY, USA: Plenum Press, 1994, pp. 81–95. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-9383-3_6.

[2] R. McCarty, "The fight-or-flight response: A cornerstone of stress research," in Stress: Concepts, Cognition, Emotion, and Behavior. San Diego, CA, USA: Academic Press, 2016, pp. 33–37.

[3] V. E. Zamoscik, S. N. L. Schmidt, M. F. Gerchen, C. Samsouris, C. Timm, C. Kuehner, and P. Kirsch, “Respiration pattern variability and related default mode network connectivity are altered in remitted depression,” Psychological Medicine, vol. 49, no. 15, pp. 2532–2540, 2019, doi: 10.1017/S0033291717003890.

[4] I. Homma and Y. Masaoka, "Breathing rhythms and emotions," Experimental Physiology, vol. 93, no. 9, pp. 1011–1021, 2008.

[5] P. M. Lehrer, E. Vaschillo, and B. Vaschillo, "Resonant frequency biofeedback training to increase cardiac variability: Rationale and manual for training," Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 177–191, 2000. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1009554825745.

[6] A. Zaccaro, A. Piarulli, M. Laurino, E. Garbella, D. Menicucci, B. Neri, and A. Gemignani, "How breath-control can change your life: A systematic review on psycho-physiological correlates of slow breathing," Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, vol. 12, p. 353, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2018.00353.

[7] E. Vlemincx, D. Vigo, D. Vansteenwegen, O. Van den Bergh, and I. Van Diest, "Do not worry, be mindful: Effects of induced worry and mindfulness on respiratory variability in a nonanxious population," International Journal of Psychophysiology, vol. 87, no. 2, pp. 147–151, 2013. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2012.12.002.

[8] V. Zamoscik, S. Schmidt, C. Timm, C. Kuehner, and P. Kirsch, "Modulation of respiration pattern variability and its relation to anxiety symptoms in remitted recurrent depression," Heliyon, vol. 6, no. 7, e04261, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04261.Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04261.

[9] X. Ma, Z. Q. Yue, Z. Q. Gong, H. Zhang, N. Y. Duan, Y. T. Shi, G. X. Wei, and Y. F. Li, "The effect of diaphragmatic breathing on attention, negative affect and stress in healthy adults," Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 8, p. 874, 2017. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00874.

[10] E. M. Sibinga, "‘Just this breath…’ How mindfulness meditation can shift everything, including neural connectivity," EBioMedicine, vol. 10, pp. 21–22, 2016. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.07.037.

[11] C. Bahi, M. Irrmischer, K. Franken, et al., "Effects of conscious connected breathing on cortical brain activity, mood and state of consciousness in healthy adults," Current Psychology, vol. 43, pp. 10578–10589, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-05119-6.

[12] R. J. S. Gerritsen and G. P. H. Band, "Breath of life: The respiratory vagal stimulation model of contemplative activity," Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, vol. 12, p. 397, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2018.00397.

[13] M. Y. Balban, E. Neri, M. M. Kogon, L. Weed, B. Nouriani, B. Jo, et al., "Brief structured respiration practices enhance mood and reduce physiological arousal," Cell Reports Medicine, vol. 4, no. 1, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100895.

[14] H. Hamasaki, "Effects of diaphragmatic breathing on health: A narrative review," Medicines (Basel), vol. 7, no. 10, p. 65, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.3390/medicines7100065.

[15] V. Zamoscik and R. Kriz, BAT – Bewusstes AtemTraining Manual für Trainer:innen, Version 2, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.29531.37925

[16] H. J. Tsai, T. B. J. Kuo, G. S. Lee, and C. C. H. Yang, "Efficacy of paced breathing for insomnia: Enhances vagal activity and improves sleep quality," Psychophysiology, vol. 52, no. 3, pp. 388–396, 2015. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.12333.

Figure Sources

Figure 1: https://pixabay.com/photos/woman-girl-meditate-relax-calm-8563442/

Figure 2: https://pixabay.com/photos/meditate-man-forest-outdoors-relax-7831951/

Figure 3: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/379330335_BAT_-_bewusstes_Atemtraining (p.33)