Scrolling against hate: Developing critical media competence to counter online antisemitism

Reviewers: Fiona Kazarovytska and an undisclosed reviewer.

Editorial assistant: Zoey Chapman.

Social media connects – but also divides. This article explores how antisemitism appears online, why young adults are especially vulnerable, and what we can do about it. Based on existing research, it offers practical tools to build media competence and promote responsible, intentional communication in the fight against online hate.

Social media platforms connect people across geographic and cultural boundaries, but they also fulfill a more negative purpose, increasingly serving as spaces for the spread of exclusionary, uncivil communication and speech [1]. Antisemitism thrives on such dynamics, allowing the spread of old antisemitic narratives, disguised in new clothing [2]. Often subtle, it adapts historical prejudices to modern debates. Social media not only presents but amplifies antisemitism through algorithms [2] and interactive features [3]1. People who spend significant portions of their lives in digital environments encounter antisemitism online but often struggle to recognize it or respond effectively [4]. While true of users of all ages, 18-to-25-year-olds are particularly at risk, given that they spend the most time online and are in an identity-shaping phase of their lives [3]. This article outlines how antisemitism manifests on social media, explores why emerging adults have difficulty engaging with it, and presents promising educational pathways, including one of the few empirically tested trainings available addressing these challenges.

The multifaceted landscape of antisemitic hate

Contemporary antisemitism on social media appears in multiple forms, disguising classical tropes within socio-political discourse. It surfaces as explicit slurs [5], coded language [6], or memes, hashtags, and emojis [3]. Most insights come from automated language detection [7], yet few studies consider what media users actually encounter as part of their day-to-day media consumption. To explore this, we asked 47 young adults in Germany to keep a diary of the social media content about Jewish people and Jewish life they encountered during their daily scrolling activities over three weeks [3]. Of 1,024 threads submitted, 59% were potentially antisemitic2. When broken down into smaller units, such as comments, images, and videos, 25% were potentially antisemitic – often just a few comments or emojis altering the tone of an otherwise neutral thread. Thus, hateful content often lurks even in non-antisemitic threads, subtly but treacherously altering their tone and broader discourse [3].

Most antisemitic content is implicit (65% in our study [3]; see also [8]), making its detection on social media even more complex. It operates indirectly, using language or imagery that avoids naming Jews but invokes antisemitic stereotypes or conspiracies. For example, antisemitic narratives may be projected onto Israel, framed with historic tropes, or appear as coded hashtags, memes, symbols, or softer wording that suggest hostility while remaining less obvious. They can also take the form of hints, conspiracy talk, or questions suggesting hidden meaning, often tied to seemingly unrelated material like Holocaust memorial posts or coverage of international conflicts, embedding antisemitic ideas within broader political commentary. Spotting these subtleties means understanding the codes behind them and paying close attention [3].

Because antisemitism online is shaped through constant interaction, it becomes harder to recognize. One of the most frequent forms of antisemitism is the confirmation of antisemitic content by media users, i.e., thumbs-up or heart emojis reinforcing antisemitic posts without generating new hate speech [3]. Such responses make users feel like they belong and strengthen group identity [1], but emerging adults often overlook or misperceive them as unintentional. Seeing these posts as harmful takes careful thought and resources like time, knowledge, empathy, and emotional reflection3.

Explicit antisemitism is less frequent (35% in our study [3]; see also [8]). Examples include denying the importance of remembering the Holocaust or comparing Hitler with current figures [9]. Often, explicit attacks target Israel, trivializing the Holocaust or demonizing the state [9]. According to Sharansky’s [10] 3D-theory, such attacks defame, delegitimize, and demonize Israel, questioning its right to exist. This form is especially difficult to recognize because it is often framed as a political critique without directly mentioning Jews. Antisemitic forms of Israel criticism appear to be the currently most accepted way of expressing explicit antisemitism online, making it harder for young people to notice and recognize it4.

Figure 1: Detecting and understanding antisemitic messages on social media takes cognitive effort, emotional reflection, and dialogue to identify the often hidden and coded meanings they convey.

Figure 1: Detecting and understanding antisemitic messages on social media takes cognitive effort, emotional reflection, and dialogue to identify the often hidden and coded meanings they convey.

Why young people struggle to recognize online antisemitism

Despite spending hours on Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube, young adults often fail to recognize antisemitism online [11] disguised as political commentary, humor, or free speech [12]. Its implicitness and taboo status foster coded communication, making detection more difficult [13]. For example, during group discussions with 55 young adults, participants, though highly media literate, often hesitated to label content antisemitic [14]. Even when feeling uneasy, they struggled to articulate why, saying, “It feels off, but I can’t say why.”

This hesitation comes from both the way messages are designed (implicitly, in multiple formats) and the dynamics of online exchanges (interactivity, making antisemitism seem “normal”). On the user side, young people often show a range of distancing strategies:

- Emotional discomfort: feeling overwhelmed and preferring to look away instead of engaging;

- Outsourcing the problem: assuming antisemitism is found in “other” groups (political right, older generations, rural areas), not their own social bubbles;

- Focus on intention over impact: instead of thinking about how the content might hurt Jewish people, they speculate about whether the author “meant” to be antisemitic, which shifts attention away from the harmful meaning of the post.

Consequently, young adults rarely labeled posts as antisemitic, let alone acted against them. Many felt their actions wouldn’t make a difference, worried that replying might spread the post even further, or thought they weren’t qualified to respond unless it affected them personally [14].

Some barriers (like emotional discomfort, outsourcing, or focusing on what someone meant) are shared across online hate (racism, Islamophobia, anti-Romani hate [15]). Yet others are especially strong when it comes to antisemitism. It often hides behind coded language that requires historical or political knowledge to understand. Stereotypes are projected onto Israel, making antisemitism seem like political criticism. It also draws heavily on conspiracy theories about “hidden power” or “media control.” Antisemitic ideas are often normalized in mainstream spaces, even in places that seem neutral, like Holocaust memorial posts. Taking words out of context and twisting them to spread antisemitic views also contributes to this normalization [6]. These factors underscore the need for training programs specifically addressing antisemitism.

What education can (and can’t) do:

Education is often presented by political actors and the media as a remedy to rising antisemitic hate. When antisemitic incidents occur, the education sector is promptly called upon to provide solutions and act swiftly [16]. Nevertheless, we have little empirically grounded knowledge about the impact and effectiveness of educational measures against antisemitism. Niedick and colleagues [17] reviewed existing research by searching academic databases for studies that used keywords like “antisemitism,” “education,” “prevention,” and “intervention.” Of 3855 results, only six studies empirically examined the effectiveness of antisemitism-specific trainings. While numerous training manuals produced by civil society organizations exist, empirical assessments of their effectiveness are rare.

Nonetheless, common elements of promising approaches are emerging (see [17]):

- Choosing to participate improves openness and engagement;

- Knowing about the shapes of antisemitism is not enough! Holistic approaches, integrating knowledge, emotional reflection, constructive dialogue, and practical response strategies are required;

- Perspective-taking and empathy matter, especially through contact with Jewish voices and experiences.

Niedick et al.’s [17] review shows that targeted, well-facilitated trainings can foster critical awareness and motivation to act, especially when young people are engaged not as “problems” but as allies.

New approaches to addressing online antisemitism

Future interventions should combine empirical research with educational and didactic innovation. A successful illustration of this approach is provided by the RESPOND! Media Competence Training, which was developed to build awareness, reflection, and action among emerging adults [18], [19].

The three-day RESPOND! training consists of nine interconnected modules covering: Jewish life and identity, managing emotions and tolerating uncertainty, recognizing implicit/explicit antisemitic stereotypes and ways in which they spread online through algorithms, and different ways to respond to antisemitic hate.

The training is holistic. Rather than solely focusing on the transmission of knowledge about antisemitism and its manifestations online, it emphasizes the social psychological dynamics of which they are part [3], [13]. The training’s pedagogy is grounded in Jewish ethical frameworks like Tikkun Olam (repairing the world) and Machloket (respectful disagreement), promoting Jewish social justice principles and responsibility5. These perspectives familiarize young adults with Jewish voices and support their use in own civic engagement, fostering inclusive and respectful digital spaces.

Figure 2: Holistic approaches that encourage perspective-taking and empathy are crucial to empowering young adults to reshape digital culture.

Figure 2: Holistic approaches that encourage perspective-taking and empathy are crucial to empowering young adults to reshape digital culture.

Responding in the RESPOND! Training is broken down into the 5 Rs of Responding:

- Recognize antisemitic content;

- Reflect on its many layers, different formats, and interactive features,

- Report using proper tools,

- Repost alternative, corrective content to shift narratives, and

- Retell by sharing knowledge in personal networks.

Early assessments of the effects of the RESPOND!’s Training show participants leave the training more confident and capable of recognizing and responding to antisemitism. As one participant noted, “I can no longer just scroll past a hateful post because I understand that action is necessary” [18]. Participants report an increased sense of identification and solidarity with Jewish people, boosting their willingness for collective action against antisemitism online.

Figure 3: The 5 Rs of responding outlined by the RESPOND! Media Competence Training.

Figure 3: The 5 Rs of responding outlined by the RESPOND! Media Competence Training.

Conclusion

Antisemitism on social media is widespread, subtle, and technologically amplified, making it difficult to detect or confront. The interactive nature of the content helps its spread and normalization, leaving users – especially young adults – disempowered. Beyond recognizing antisemitism, young people must also overcome emotional and identity-based barriers to engagement. Yet, innovative educational programs like the RESPOND! Training offer hope. By combining empirical insight, social-psychological understanding, and actionable strategies, they equip young people with the competence needed to challenge antisemitism online.

The takeaway is clear: if we want a digital culture rooted in empathy and solidarity, we must empower young people with critical media skills and supportive communities. Each of us has a role to play in fostering this shift – because only together can we transform online spaces from places of exclusion and hate into platforms for respect and connection.

Bibliography

[1] J. B. Walther, “Making a Case for a Social Processes Approach to Online Hate,” in Social processes of Online Hate, J.B. Walther & R. E. Rice, Eds., London, UK: Routledge, 2025, pp. 9-36. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003472148

[2] M. Hübscher, and S. von Mering, Eds., Antisemitism on Social Media. London, UK: Routledge, 2022.

[3] Ö. Odağ, A. M. Kraj, J. Niedick, J. Kohl, L. Buhin, L. P. Juang, G. Dobslaw, “Subtle constructions of antisemitism on social media: A content analysis of media diaries of emerging adults,” Submitted to the Journal of Media Psychology, under review, expected publication date end of summer 2025.

[4] M. Schwarz-Friesel, and J. Reinharz, Die Sprache der Judenfeindschaft im 21. Jahrhundert, Berlin, Germany: de Gruyter. 2013.

[5] M. J. Becker, Antisemitism in Reader Comments: Analogies for Reckoning with the Past. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021.

[6] M. Schwarz-Friesel, Judenhass im Internet: Antisemitismus als kulturelle Konstante und kollektives Gefühl. Leipzig, Germany: Hentrich & Hentrich, 2019.

[7] M. J. Becker, L. Ascone, K. Placzynta, and C. Vincent, “Introduction,” in Antisemitism in Online Communication. Transdisciplinary Approaches for the Twenty-first Century, M. J. Becker, L. Ascone, K. Placzynta, and C. Vincent, Eds., Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, pp. 1-18, 2024. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0406

[8] M. J. Becker, and H. Troschke, “Decoding implicit hate speech: The example of antisemitism,” in Challenges and perspectives of hate speech research, C. Strippel, S. Paasch-Colberg, M. Emmer, and J. Trebbe, Eds., Berlin, Germany: Digital Communication Research, pp. 335–352, 2023.

[9] International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA), Working Definition of Antisemitism, 2016. https://holocaustremembrance.com/resources/working-definition-antisemiti...

[10] N. Sharansky, “Antisemitism in 3-D. Demonization, Double standards, and Delegitimization,” Jewish Political Studies Review, vol. 16, pp. 3-4, 2004.

[11] U. K. Schmid, A. S. Kümpel, and D. Rieger, „How social media users perceive different forms of online hate speech: A qualitative multimethod study,” New Media & Society, vol. 26, issue 5, May 2022. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221091185

[12] N. B. Ocampo, E. Sviridova, E. Cabrio, and S. Villata, “An in-depth analysis of implicit and subtle hate speech messages” [Conference presentation]. 17th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Dubrovnik, Croatia. pp.1997-2013, May 2-6, 2023. DOI: 10.18653/v1/2023.eacl-main.147. hal-04214094

[13] M. Mendel, and A. Messerschmidt, Fragiler Konsens: Antisemitismuskritische Bildung in der Migrationsgesellschaft. Frankfurt/New York: Campus Verlag, 2017.

[14] A. M. Kraj, Ö. Odağ, L. Buhin, J. Kohl, G. Dobslaw, J. Niedick, L. P. Juang, “Can You Tell Me What I’m Looking At?,” in Antisemitism Online: An Ancient Hatred in the Modern World, T. Pittinsky Ed., in preparation, expected publication date end of summer 2025.

[15] L. Buhin, Ö. Odağ, A. M. Kraj, S. B. Isakov, and N. Shwartz, “’ I don’t see a way in’: Understanding Emerging Adults' Responses to Hate Speech Online. Manuscript in preparation.

[16] A. Scherr and B. Schäuble, ‘Ich habe nichts gegen Juden, aber…‘ – Ausgangsbedingungen und Ansatzpunkte gesellschaftspolitischer Bildungsarbeit zur Auseinandersetzung mit Antisemitismen. Langfassung Abschlussbericht, 2006. https://www.amadeu-antonio-stiftung.de/w/files/pdfs/schaublescherrichhab...

[17] J. Niedick, L. P. Juang, and L. Bitter, “Education against Antisemitism. A Scoping Review.” Submitted to the Journal of Research on Education, under review, expected publication date end of summer 2025.

[18] J. Niedick, L. P. Juang, J. Kohl, A. M. Kraj, L. Buhin, and Ö. Odağ, „Educational Approaches to Addressing Antisemitism on Social Media: The RESPOND! Project,” in Antisemitism Online: An Ancient Hatred in the Modern World, T. Pittinsky, Ed., in preparation, expected publication date end of summer 2025.

[19] D. Baacke, Medienkompetenz-Begrifflichkeit und sozialer Wandel, A. v. Rein, Ed., Medienkompetenz als Schlüsselbegriff, Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt, pp.112-124, 1996.

[20] M. Funk, Von Juden lernen [Learning from Jews], Munich, Germany: dtv Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG, 2024.

Figures

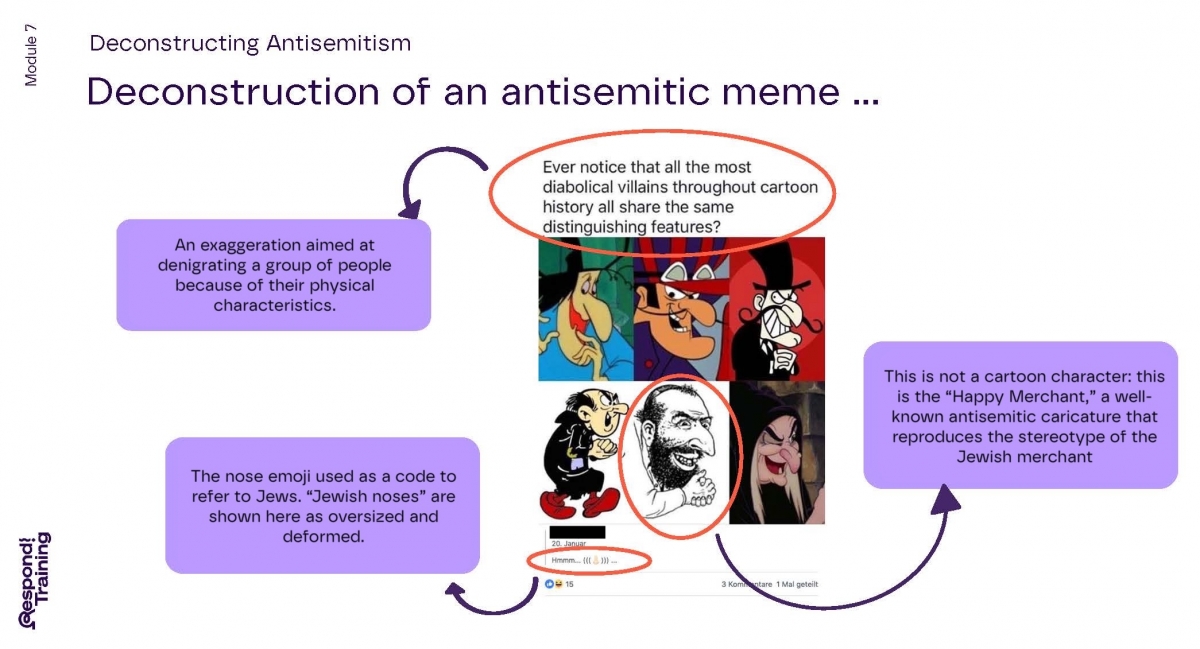

Figure 1: Sample social media post from the RESPOND! diary study; deconstruction done by the RESPOND! Team

Figure 2: Image credit Patrick Pollmeier

Figure 3: Card design Peter Reimer; card content by the RESPOND! Team

Footnotes

1Please note that [3], [14], [17], and [18] are currently under review and expected to be published by the end of the summer 2025.

2In order to be coded as such, an entire thread had to contain at least one post or comment that could be considered potentially antisemitic. We used the term “potentially antisemitic” when coding the media diaries to acknowledge that some content may contain antisemitic elements or implications, yet its interpretation depends on considering the context, asking thoughtful questions, and relevant background knowledge. We also use the term “potentially antisemitic” because some content is not inherently antisemitic on its own but can serve as an entry point or amplifier for antisemitic discourse. Finally, we use the term “potentially antisemitic” from a media competence perspective, aiming to encourage media users to examine social media content more critically and not limit their attention to only the most obvious indicators of antisemitism

3We let our participants decide what to include in their media diaries. Instead of giving them a strict definition of antisemitism, we asked them to show us the kinds of posts that naturally appeared in their social media feeds, based on how they understood Judaism and Jewish life. Because social media feeds are so personalized, a different group of participants would likely have shown us different content. This approach allowed us to capture their unique online experiences with hateful material. What stood out, however, was that participants came across antisemitic content without searching for it – it was hiding in plain sight among everyday posts.

4The critique of the State of Israel or its actions is certainly not inherently antisemitic. However, instances of such objective and neutral criticism in our data were almost entirely absent. Furthermore, there is a lack of sustained efforts to create a better understanding of what legitimate Israel criticism looks like (for a more elaborate discussion, see [3]).

5Our understanding of Jewish social justice principles and responsibility has been shaped by expert interviews (available on www.respond-training.de website under “Jewish social ethics”) and Mirna Funk’s book “Learning from Jews” [original: “Von Juden lernen”] [20]. Both point to the importance of questioning what we consider as facts, culture of debating and constructive disagreement, empathy and solidarity, as well as a shared responsibility to better the world around us. These are also the principles that we seek to impart in our training.