Bug or feature? Boredom feels aversive, and this is why it matters

Editorial Assitants: Stella Wernicke, Jana Dreston

Note: An earlier version of this article has been published in the German version of In-Mind.

In class, during exercise, at work: boredom is an everyday experience that is generally regarded as an annoying and rather useless nuisance. In keeping with this attested uselessness, boredom had not gathered much research interest for a long time. Fortunately, this has changed and new and exciting research paints a different picture of boredom, highlighting its function and its relevance for human behavior. Indeed, boredom appears to play a key role in goal-striving because it acts as a catalyst for change. Simply put, boredom tells us that we are wasting our resources and that we should look for other things to do. To provide an overview of the emerging research on boredom, this article covers what boredom is, when it occurs, what it does, and why it matters.

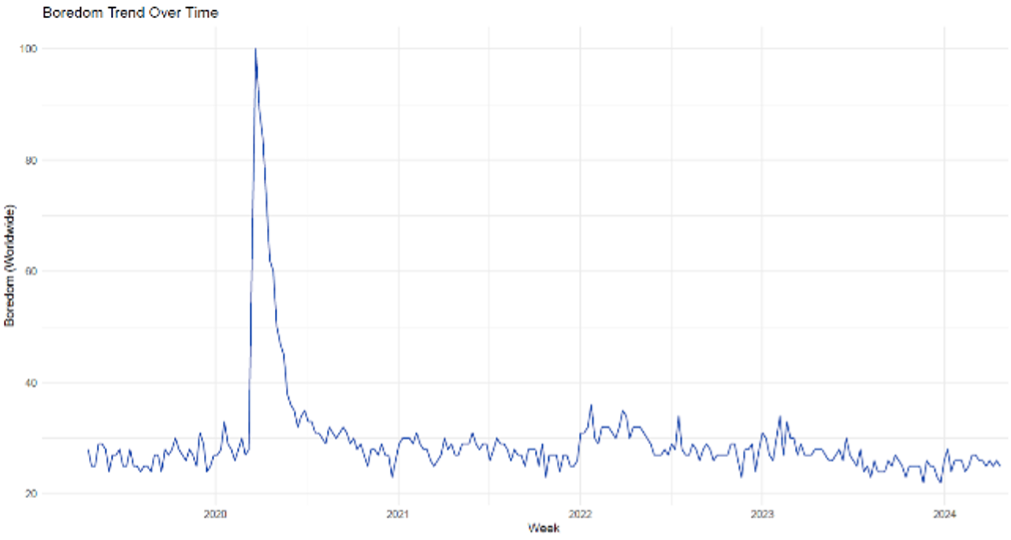

During the COVID-19 pandemic, people experienced unprecedented restrictions of their everyday activities: Social contacts had to be curbed, life predominantly took place within one's own home, and opportunities for leisure activities were scarce. These lockdowns and behavioral restrictions were implemented to slow the spread of the pandemic. At the same time, these restrictions appear to have acted as a catalyst for boredom to enter peoples’ life and the collective discourse. Indeed, a look into worldwide Google Search Trends reveals that boredom spiked as a search term during the time substantial restrictions were imposed (see Figure 1).

Worldwide Google search trends for the term boredom between Spring 2019 and Spring 2024. The data show that the popularity of boredom as a search term spiked in the spring of 2020 (i.e., when many countries imposed stricter measures to slow the spread of the pandemic) and then normalized rather quickly back to prior levels. Note. The value on the Y-axis reflects the relative popularity of a search term over the analyzed timeframe.If we look at how boredom has been conceptualized by researchers, the apparent spike in boredom during the pandemic makes a lot of sense. In a landmark paper, Eastwood et al. [1] broadly characterized boredom as an aversive state one experiences when the current situation is unsatisfying and the pursuit of more rewarding alternatives is thwarted. This seems like a good description of how many people felt during the pandemic: sat at home and being unable to meet their friends or pursue their hobbies. Sustaining such an aversive state for a prolonged time requires amounts of effort that people might not be willing (or able) to muster consistently. Indeed, boredom was not merely a personal nuisance during the pandemic, but also a detriment to COVID-19 containment measures: Boredom prone people (i.e., people with a strong disposition to perceive their life as boring) were more likely to break social-distancing rules, and stated that adhering to these guidelines was particularly difficult for them [2]. Examples like this highlight boredom’s reputation as an annoying but unavoidable nuisance. Fostering this poor reputation, studies have identified a host of negative consequences of boredom [3]. However, before we will take a closer look at the consequences of being bored, it is important to get a better understanding about what boredom actually is, how it occurs, and why it is a uniquely important human sensation.

What is boredom, how does it occur & what is its function?

We define boredom as a state where a person feels they are not adequately utilizing their mental or physical functions [4]. Simply put, boredom signals that we are wasting our resources [2]. This is typically the case when the current activity is inconsistent with what one likes to do (preferences), is able to do (capabilities), and/or feels energized to do (perceived energy). This can be illustrated by the example of a student who gets bored in an introductory statistics class. The student might prefer to learn advanced topics, have the capabilities to comfortably do so, and she might feel sufficiently energized to really dive into the topic. Here, the introductory statistics class would neither align with her preferences, her capability, nor her available energy, making it more likely that she feels she is not putting her mental and physical faculties to good use (Importantly, what is “good use“ lies in the eye of the beholder and should not be confused with things that would unequivocally be considered “good use“).

Image 1

Image 1Probably the most prototypical situation for the experience of boredom is school. Students get bored when they are not optimally challenged (e.g., excessive demands in math) and attach little value to the lessons (e.g., no interest in math).

To better understand and predict when boredom occurs, researchers rely on different theoretical frameworks that specify precursors of boredom. Many readers can probably relate to the example of the bored student (maybe for the opposite reasons). In turn, it is probably no surprise that much of what we know about boredom comes from educational psychology research, trying to understand why students get bored in class and how this can be avoided. This research has largely been conducted through the lens of Reinhard Pekrun’s influential Control-Value Theory (CVT) [5]. Most generally, CVT describes how emotions occur in learning and performance contexts, and, as its name suggests, perceptions of control and value are thought to determine the emotions one experiences during a task. Importantly, although boredom differs considerably from how emotions are typically conceptualized [4], CVT has proven to be a highly useful framework to study when people get bored [5].

With respect to control, CVT states that people become bored when they have too much or too little control over the situation they are in. This means that a high-achieving student and a low achieving student might be bored in the same class because to the former it feels too controllable and to the latter it feels uncontrollable! So, control demands of a task – say, the topics covered in the aforementioned statistics class - should neither be too high nor too low in order to avoid boredom. The other key factor in CVT is the concept of value: people become bored during activities they find meaningless or unimportant. Most readers can probably remember specific classes in school or university that they found uninteresting or meaningless. According to CVT, boredom is most pronounced when both

factors occur together, i.e., during activities that feel like they have no value and that feel either too challenging or too easy.

It is the link to low value that makes boredom different from other emotional states, as these are typically experienced in situations of high positive (e.g., joy of diving into an interesting topic) or high negative value (e.g., fear of an upcoming exam). Thus, boredom does not seem to completely fit the bill of a typical emotion, but might be a more fundamental human

sensation, simply telling us that an ongoing activity is a waste of resources.

Although CVT was developed to explain how emotions occur in academic settings, more recent theoretical work makes very similar predictions for boredom in general e.g., [6]. This suggests that irrespective of the specific context, boredom occurs due to an interplay of inadequate control-value appraisals. This can be vividly illustrated for other learning and performance contexts. One such context is sports and exercise. In sports, situations can easily be overwhelming. For example, by setting unreasonably high training targets or by competing against opponents who are much better than oneself. Likewise, sports and exercise can also be underchallenging. For example, think of an endurance athlete who is asked to train at very low intensities for long durations or a basketball player who has to practice the same basic free throw movement again and again. In addition, exercise might induce boredom if exercising has little value to the exerciser. This might be particularly likely in the context of health-oriented sports if exercise merely functions as a prescribed means to an end (for example, to lose weight or as part of a physical rehabilitation program) and is not done because one actually values the act of exercising. Thus, inadequate training goals in conjunction with finding little value in the act of exercising can promote boredom in sports. Such conditions might deter people from doing sports in the first place, or make it harder for them to stick to their exercise plan. Showcasing how much boredom matters in sports and exercise contexts, one can find numerous tips on how to fight exercise-induced boredom in online message boards or the media. While probably many readers and the “internet in general” might agree that sports and exercise can be outright boring, research has long neglected the role boredom might play in this context. Fortunately, this is changing and researchers have started to assess boredom during sports. This emerging line of research shows for example that boredom prone people exercise less, that boredom can affect sports performance, and that, consistent with CVT, control-value appraisals affect boredom in sports (for a review on boredom in sports and exercise, please see [7]).

Bored to death? Boredom matters!

“Bored to death” – an epidemiological study suggests that this figure of speech might contain a grain of truth: Britton and Shipley [8] found that the risk of dying from a cardiorespiratory disease was 2.5 times higher among people who reported frequent boredom compared to people who were rarely bored. Importantly, the link between boredom and mortality was not

significant after the authors statistically controlled for lifestyle

factors, such as physical activity behavior. This suggests that boredom itself might not increase mortality, but rather that being bored could lead to maladaptive behaviors that increase the risk for certain diseases. This reasoning is consistent with research showing that boredom prone people exercise less than people who are rarely bored. Importantly, there are various routes through which boredom can be detrimental to a healthy lifestyle. For example, people might refrain from engaging in healthy but potentially boring activities, such as exercising, flossing or going to medical check-ups. At the same time, boredom might promote engagement with various unhealthy activities that promise a quick escape from boredom. Exemplary boredom avoiding behaviors that have been linked with high boredom proneness are drug and alcohol abuse or excessive gambling [3]. An even more drastic illustration of the

power boredom can exert over peoples’ behavior was published 2014 in the academic journal Science: The authors found that (some) participants would voluntarily self-administer electronic shocks in order to distract themselves from boredom [9]. Importantly, prior to this, participants had rated these shocks as being extremely aversive. In addition to promoting self-harming behavior, a series of nine studies showed that boredom can also promote sadistic aggressive behavior towards other people [10].

The desires to avoid and to escape boredom can also affect behavior simultaneously. For example, a person might choose to avoid the anticipated boredom that would occur during exercise and stay on the couch to watch TV instead. While sat on the couch and browsing Netflix, they might then turn to unhealthy snacks and drinks to reduce boredom.

Crucially, boredom does not only matter for health behavior. As we have already mentioned, boredom plays a prominent role in academic contexts. It is these contexts, where the negative effects of boredom have most frequently been shown. For example, findings from a

meta-analysis revealed a negative relationship between boredom and performance in the academic context (r = -.24; [11]). One likely reason for this relationship is the effect boredom has on attention: Boredom directs attention away from one’s current activity, thereby making it harder for students to focus on class. In light of the importance boredom plays for academic performance, it seems instructive to directly ask students about their boredom in class evaluations. This would help teachers make classes less boring and help students to develop effective strategies to reduce boredom in class.

The importance of boredom: signaling the need for change

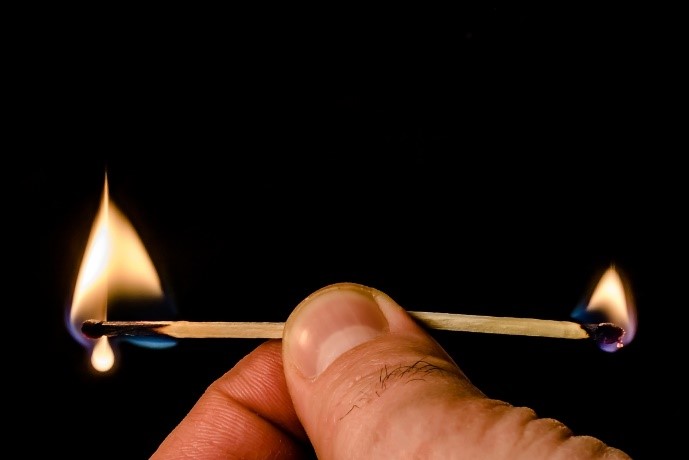

In light of how aversive boredom feels and the host of negative consequences it begets, one might ask why this annoying sensation exists in the first place. Does boredom have a function? Boredom researchers James Danckert and John Eastwood [12] use the example of pain as an aversive but highly useful sensation to answer this question for boredom: The function of pain lies not in hurting people, but to signal imminent danger of bodily damage. To provide a simple illustration, pain acts as a strong signal to quickly remove one’s hand from a hot stove to prevent tissue damage. In a similar vein, the function of boredom does not lie in annoying us as for no reason, but it acts as a signal that one’s current situation needs to be changed: Boredom is understood to act as a signal that whatever one is currently doing is not worth our while and that one should search for more rewarding alternatives.

Image 2

Image 2Pain is unpleasant and signals that physical harm is imminent – for example, if you hold on to burning matches for too long. Similarly, boredom is also experienced as an aversive sensation that signals that you should change something about the current situation.

Importantly, boredom gives no direction as to how the situation should be changed. It should rather be understood as an impartial signal to do something else. A very nice illustration of this impartiality comes from a series of experiments where participants had first watched positive, negative, or neutral pictures [13]. Irrespective of the type of pictures participants had watched, watching the pictures became boring after a while. In the second part of the study, they were again instructed to watch a series of pictures, but now they were allowed to choose if they would rather want to watch similar or different pictures than before. Consistent with the idea that boredom pushes us to do something else, participants tended to choose pictures that represented the hedonic opposite to the pictures they had watched before: If they had watched negative pictures in the first series, they were more inclined to choose positive pictures in the second series, and vice versa. These findings are consistent with the idea that boredom functions as a signal for exploration, to do something new.

If boredom is indeed just an impartial signal to change what one is currently doing, then boredom should not exclusively lead to maladaptive behavioral choices but should also promote positive outcomes. Interestingly, research that has investigated boredom as a driver for

adaptive choices is scarce because most studies focus on negative consequences of boredom. As an interesting exception to this focus on the negative, van Tilburg and Igou investigated the effect boredom has on

prosocial behavior [14]. As boredom occurs in situations that are perceived as meaningless,

prosocial behavior could be a way to reduce boredom because it carries personal and societal value. Consistent with this thought, the study showed that bored people were more willing to donate money for charity. This finding provides an interesting contrast to the findings on boredom as a driver of sadistic aggression and highlights that people can respond in positive and negative ways to boredom. Interestingly, recent work shows that

adaptive and maladaptive responses to boredom seem to reflect rather stable individual differences that can be measured with the Dealing with Boredom Scale [3]. Thus, for some people, boredom tends to promote

adaptive behavior (e.g., being creative, getting stuff done), whereas for others boredom might promote maladaptive choices (e.g., gambling, drug use).

Boredom promotes exploration and complements the function of willpower

Boredom drives behavioral adjustments. As we have illustrated, boredom acts as an undirected signal to do something else, thereby promoting

adaptive and maladaptive behaviors alike. The undirected search for other things to do is also referred to as random exploration. Following the urge to explore can provide us with many new experiences. However, if one would always give in to this urge, one would be unable to consistently pursue a

goal. Willpower, in research contexts mostly referred to as

self-control, plays a key role for the pursuit of long-term goals.

In life, people have to constantly weigh the relative benefits of staying on task (e.g., continuing with my exercise) and exploration (e.g., stopping at the beautiful lake I am running at and enjoy the scenery) against each other. Current research assumes that boredom and

self-control have complementary roles in helping people navigate this trade-off [15]. Consistent with this, a large body of research shows that boredom and

self-control are negatively correlated: People who report to have low

self-control tend to struggle with the regulation of boredom and the pursuit of long-term goals [15].

Beyond individual differences, a compelling illustration of the interplay between boredom and

self-control on the level of an isolated task comes from research on the much-discussed “ego depletion” phenomenon [16]. Based on the assumption that

self-control relies on a limited resource that can become temporarily depleted, participants are asked to either work on a high control task (e.g., copying a written text but omitting specific letters) or a low control task (e.g., simply copying a written text). Through the lens of ego depletion research, the availability of

self-control resources should be lower after completing a

self-control demanding task, and this should in turn lead to impaired performance on a subsequent task that also requires

self-control. Through the lens of boredom research, such designs miss a crucial

feature of how these tasks differ: The low-control task typically is very monotonous and underchallenging, thereby making it an almost ideal boredom induction task. Indeed, the very same tasks that are used as low control tasks in ego depletion research are sometimes used as boredom tasks in boredom research!

But why is this a problem? As we have illustrated, boredom acts as a signal for exploration, to do something else. Ironically, the boredom-induced urge to disengage from the task at hand (e.g., to stop copying a written text), necessitates additional

self-control to not give in to the urge to explore but to stay engaged with current activity. In turn, it is not clear to what degree the

self-control demands of a supposed high control task and low control task actually differ. This might (at least partly) explain the heterogeneous and inconsistent literature on the ego depletion phenomenon [16]. Indeed, a couple of recent studies have shown that boredom differs between high and low control tasks in ego depletion research and that boredom affects how people perform in these tasks [15], [17].

We have highlighted the potential for boredom to distort findings in the context of ego depletion research. We have chosen this example because of the heterogeneous literature in this

field and because the ego depletion idea has been very appealing to the general public (as reflected in the proliferation of popular books that touch on the topic). That being said, boredom appears to act as an uncontrolled confound in many behavioral science studies [18]: We asked experienced research participants about their general experience of boredom when participating in behavioral science studies and if they felt this affected their behavior and study outcomes (Figure 2).

![Figure 2 Self-reported experience of boredom and its effects when participating in behavioral science studies, as published in [18]. Here, participants reported how much they agreed to various statements about the role and effects of boredom while participating in a typical study.](/sites/default/files/figure_2_1.png) Figure 2

Figure 2Note. Results are reported separately for a sample of n = 113 university students and n = 419 paid online workers.

Worryingly, many participants not only reported getting bored when participating in studies, but a large number of participants also affirmed that they altered their behavior due to boredom and that they felt this affects study outcomes in general.

Conclusion

Summing up, boredom is an aversive everyday experience that has experienced a substantial increase in research interest. Current evidence suggests that although boredom has been empirically linked to a plethora of negative consequences, it fulfills a function that is central to human functioning: By signaling that one is not putting one’s resources to adequate use, boredom signals the need to do something else, thereby acting as a catalyst for exploration. Importantly, boredom seems to be quite effective in steering us away from situations that feel like a waste of time and helping us find new and more rewarding things to do: If one takes another look at Figure 1, one can see that the massive spike in boredom appears to normalize very quickly to baseline levels, indicating that people were relatively quick to adjust to the COVID-19 situation and found ways to spend their time without excessive boredom.

Further, research suggests that boredom complements the function effortful willpower has for

exploitation. It thereby contributes to how people navigate the tradeoff between exploration and

exploitation in everyday life. Given its long overlooked fundamental role in human behavior, it is great to see that more and more researchers have started to become intrigued by boredom and their work has led to substantial advancements in our understanding of boredom. Their work has now been summarized in the first comprehensive handbook on boredom research [19], and we are convinced that this will serve as a further catalyst for boredom research (Figure 3). Because to us, boredom is anything but boring and with this text it was our aim to highlight why boredom is fascinating and relevant.

Image 3

Image 3Research on boredom is flourishing: In spring 2021, the “International Society of Boredom Studies” was founded, dedicated to promoting and disseminating research on the topic of boredom (A). Recently, the first textbook on boredom research and its broad relevance to various research topics was published (B).

Image 1: Saydung89 via Pixabay (https://pixabay.com/illustrations/girl-bored-sleepy-boredom-couch-5835891/, Lizenz:https://pixabay.com/service/license/).

Image 2: Myriams-Fotos via Pixabay (https://pixabay.com/photos/matches-burnout-disease-mental-pain-2109344/. Lizenz:https://pixabay.com/service/license/).

References

[1] J. D. Eastwood, A. Frischen, M. J. Fenske, and D. Smilek, “The Unengaged Mind: Defining Boredom in Terms of Attention,” Perspect. Psychol. Sci., vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 482–495, Sep. 2012, doi: 10.1177/1745691612456044.

[2] W. Wolff, C. S. Martarelli, J. Schüler, and M. Bieleke, “High Boredom Proneness and Low

Trait

Self-Control Impair Adherence to Social Distancing Guidelines during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health, vol. 17, no. 15, p. 5420, Jul. 2020, doi: 10.3390/ijerph17155420.

[3] M. Bieleke, L. Ripper, J. Schüler, and W. Wolff, “Boredom is the root of all evil—or is it? A psychometric network approach to individual differences in behavioural responses to boredom,” R. Soc. Open Sci., vol. 9, no. 9, p. 211998, Sep. 2022, doi: 10.1098/rsos.211998.

[4] W. Wolff, V. C. Radtke, and C. S. Martarelli, “Same same but different,” in The Routledge International Handbook of Boredom, 1st ed., London: Routledge, 2024, pp. 5–29. doi: 10.4324/9781003271536-3.

[5] P. Pekrun and T. Goetz, “Boredom: A Control-Value Theory approach,” in The Routledge International Handbook of Boredom, 1st ed., London, 2024, pp. 74–90.

[6] E. R. Igou, M. K. O’Dea, K. Y. Y. Tam, and W. A. P. van Tilburg, “Boredom and the Quest for Meaning,” in The Routledge International Handbook of Boredom, Routledge, 2024, pp. 90–105.

[7] W. Wolff, C. Weich, and U. Fischer, “Boredom in Sports and Exercise.” Feb. 23, 2023. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/y6dkw.

[8] A. Britton and M. J. Shipley, “Bored to death?,” Int. J. Epidemiol., vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 370–371, Apr. 2010, doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp404.

[9] R. C. Wilson, A. Geana, J. M. White, E. A. Ludvig, and J. D. Cohen, “Humans use directed and random exploration to solve the explore–exploit dilemma.,” J. Exp. Psychol. Gen., vol. 143, no. 6, pp. 2074–2081, 2014, doi: 10.1037/a0038199.

[10] S. Pfattheicher, L. B. Lazarević, E. C. Westgate, and S. Schindler, “On the

relation of boredom and sadistic aggression.,” J. Pers. Soc. Psychol., vol. 121, no. 3, pp. 573–600, Sep. 2021, doi: 10.1037/pspi0000335.

[11] V. M. C. Tze, L. M. Daniels, and R. M. Klassen, “Evaluating the Relationship Between Boredom and Academic Outcomes: A

Meta-Analysis,” Educ. Psychol. Rev., vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 119–144, Mar. 2016, doi: 10.1007/s10648-015-9301-y.

[12] J. Danckert and J. D. Eastwood, Out of My Skull: The Psychology of Boredom. Harvard University Press, 2020. doi: 10.4159/9780674247079.

[13] S. W. Bench and H. C. Lench, “Boredom as a seeking state: Boredom prompts the pursuit of novel (even negative) experiences.,” Emotion, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 242–254, Mar. 2019, doi: 10.1037/emo0000433.

[14] W. A. P. Van Tilburg and E. R. Igou, “Can boredom help? Increased prosocial intentions in response to boredom,” Self Identity, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 82–96, Jan. 2017, doi: 10.1080/15298868.2016.1218925.

[15] M. Bieleke, W. Wolff, and A. Bertrams, “On the Virtues of Fragile

Self-Control: Boredom as a catalyst for

adaptive behavior regulation,” in The Routledge International Handbook of Boredom, Routledge, 2024, pp. 133–144.

[16] W. Wolff and C. S. Martarelli, “Bored Into Depletion? Toward a Tentative Integration of Perceived

Self-Control Exertion and Boredom as Guiding Signals for

Goal-Directed Behavior,” Perspect. Psychol. Sci., vol. 15, no. 5, pp. 1272–1283, Sep. 2020, doi: 10.1177/1745691620921394.

[17] T. Mangin, N. André, A. Benraiss, B. Pageaux, and M. Audiffren, “No ego-depletion effect without a good control task,” Psychol. Sport Exerc., vol. 57, p. 102033, Nov. 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.102033.

[18] M. Meier, C. S. Martarelli, and W. Wolff, “Is boredom a source of noise and/or a confound in behavioral science research?,” Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun., vol. 11, no. 1, p. 368, Mar. 2024, doi: 10.1057/s41599-024-02851-7.

[19] M. Bieleke, W. Wolff, and C. Martarelli, Eds., The Routledge International Handbook of Boredom. London: Routledge, 2024. doi: 10.4324/9781003271536.