How body language helps us understand other people’s emotions

Editorial Assistant: Stephanie Davey

Note: An earlier version of this article has been published in the German version of In-Mind.

Social interaction is a complex phenomenon. When we want to know what our fellow human beings are feeling, we have various sources of information at our disposal. One major source is the human body and body language. By observing another person’s body language, we can infer not only what they are doing but also why they are doing it and even what they are feeling at the time. But how well can we really recognize emotions from movements? How do we manage to deduce other people’s feelings by observing their movements, and how does this ability differ from person to person?

She stroked his cheek in one fluid movement. He took her in his arms and hugged her tightly. She nestled against him and buried her head in his chest.

When watching such a scene, we gain an immediate and almost intuitive understanding of the physical actions, the underlying intentions, and the innermost feelings of the people involved. For example, we recognize a gentle tenderness in the smooth flow of the caress and conclude that they are

feeling strong affection. But how can we draw such complex conclusions so effortlessly—based merely on characteristics of their movements?

In the very first months of life, we already develop a special sensitivity for emotional body movements. One study showed that 5-month-old babies spent more time watching videos of emotional body movements when these were paired with emotionally appropriate vocal sounds. For example, when angry body movements were presented with angry voices, the babies watched the videos for longer than when angry movements were paired with happy voices. This suggests that even very young babies are already able to match emotional body movements to the corresponding vocal expression of the emotion, and are therefore able to recognize emotions on the basis of body movements [1].

Why this works so early in life is certainly due to the fact that we are social beings. We spend a great deal of time in the company of others. Accordingly, perceiving their intentions and emotions is one of our core skills that contribute decisively to making a success of communication, relationships, and society.

The body as a source of information

The crucial importance of being able to perceive emotions is particularly emphasized by the breadth of different information channels through which we can convey emotional states. One major information channel is the body. By observing a person’s body language, we can determine what they are doing, why they are doing it, and even the feelings associated with it. This phenomenon is known as emotional body language [2]. What makes it so special is that it does not just contain information about a person’s emotional state, but also tells us how to behave appropriately in a specific situation [2]. For example, if we see an angry face, we do not know immediately whether we are in danger and should flee, or whether some calming words will suffice. However, if we see the other person running toward us with raised fists, we quickly realize that the first behavioral alternative might well be the better option.

What information do we take from body language in order to recognize emotions?

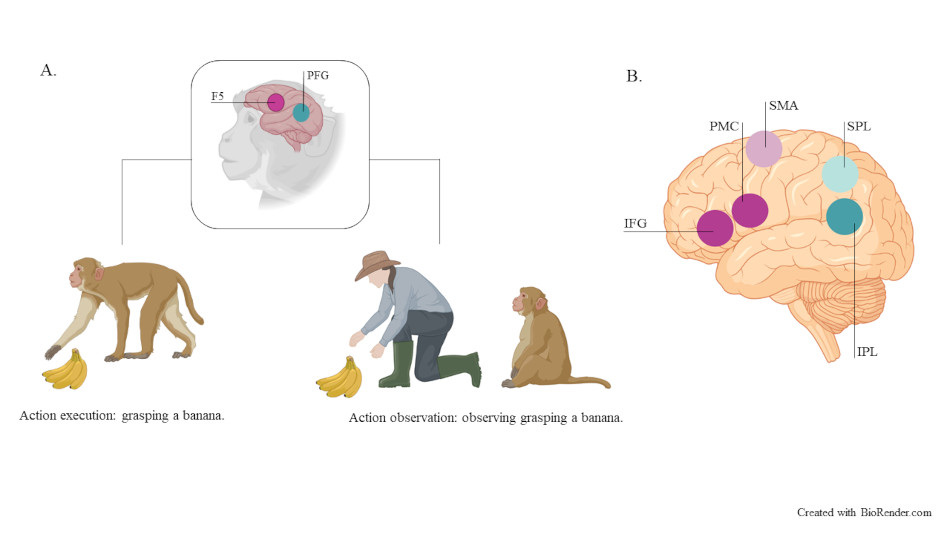

One question that emerges here is which features of body language do we use to draw specific conclusions about other people`s feelings. One way to investigate this is to use point-light displays. Such displays present a moving person in the form of only a few white dots against a dark background marking their joints and extremities (Figure 1). This reduces a person’s behavior to nothing more than the movement of these joint points, has the advantage of removing any other person-specific features such as facial expressions, and allows us to draw direct conclusions on the role of movement characteristics in recognizing emotions. We can also change such representations systematically or focus on individual characteristics of a movement such as its speed. This is of particular interest when studying the role of different body parts or different characteristics of a movement.

One recent study used point-light displays to determine which parts of a moving body contain central information that others can use to recognize different emotions. Subjects observed two variants of a point-light display of emotional scenarios. These showed movements of either the trunk or the arms. Results showed that anger and happiness are recognized better from hand movements, whereas sadness is recognized better from movements of the trunk. Hence, it seems that we are able to recognize another person’s emotions because different body parts provide different characteristic information on the expression of different feelings [3].

A further study used such point-light displays to ascertain which characteristics of a movement play a decisive role in evoking the impression of a specific emotion in observers. Subjects were asked to classify emotional interactions between two people presented as point-light displays. Then the movements of the observed persons were analyzed and compared with the emotional impressions they had made on the test subjects. Results showed that emotional impressions are shaped by very specific movement characteristics. For example, the speed of an observed body movement plays a special role: People are more likely to perceive sadness when the scene they observe is characterized by little activity, slowness, and sluggish movements. On the other hand, they are more likely to perceive joy or anger when movements are highly expansive and fast [4].

These studies show that we usually find it easy to recognize the emotional content of such simple representations. We gather and interpret the information we use for this in a very short time, and our perceptual impression is determined by those features of body language that are characteristic for different emotions.

I feel what you feel: Simulation theory

What underlying neural mechanisms can explain how we use our observations of body language to recognize others’ emotions? One much-discussed idea is that we actually simulate the actions and feelings we observe. Simulation is understood here as the construction of a mental state resembling that of the other person, thereby enabling us to recognize their intentions, their emotions, and their motivation. We do this by using our own neural representations of these very same states (so-called shared representations) [5], [6].

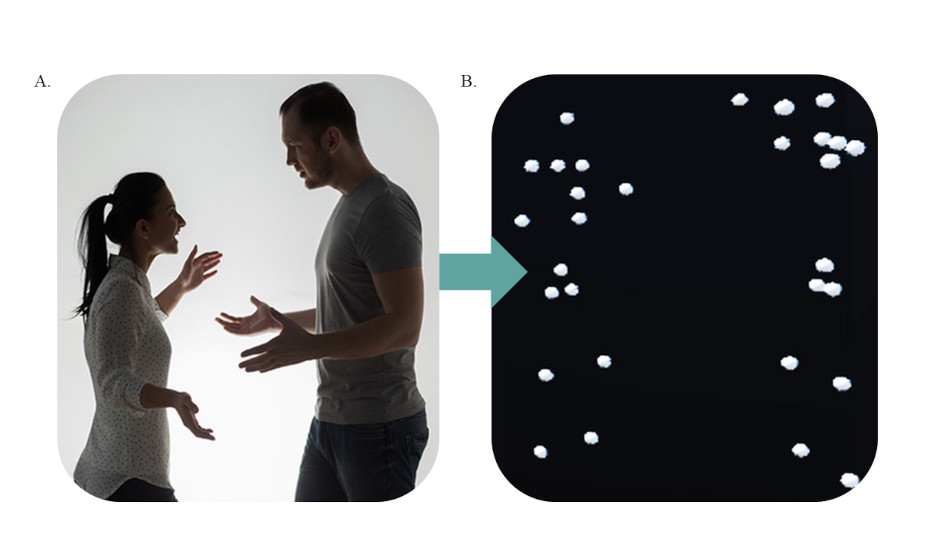

This idea first emerged in the mid-1990s with the discovery of so-called mirror neurons. Initial experiments had shown that neurons in motor parts of the brain of macaques were not just activated when reaching for a peanut but also when observing conspecifics or even humans performing the same action (Figure 2) [7]. Hence, these mirror neurons are nerve cells that are activated when both observing and performing movements. In other words, they represent a resonance mechanism, a reflection of the observed action. Ever since these experiments, mirror neurons have been regarded as a fascinating neural basis for how we understand the actions of others.

Of course, one major criticism of these findings is that they came from experiments with macaques. However, initial evidence from research based on

imaging techniques [8] revealed similar neural mechanisms in humans. Subjects were placed in a

functional magnetic resonance imaging scanner and asked not only to perform movements but also to observe the same movements in others. Results showed neural activation in areas corresponding to the location of mirror neurons in the macaque brain. This was seen as the first indirect evidence that areas in the human brain also possess mirror properties that enable us to simulate actions and movements on the basis of our own motor representations.

The final confirmation of mirror neurons in humans came a few years later through measuring the activity of individual nerve cells while performing and observing specific actions. This study found nerve cells that were active not only when grasping an object but also when observing that object being grasped [9].

More recent research has shown that this mirror mechanism also underlies our understanding of other people’s emotional states. One study showed that when observing other people expressing disgust, areas of the brain associated with feelings of disgust are active [10]. Put simply, this means that we recognize a specific emotion in others because it is activated in ourselves. This can enable us to understand the emotion we observe in another person’s facial expressions.

However, mirror neurons and

motor simulation are not the only explanation for all the complex psychological processes involved here that range from the

recognition of intentions and emotions up to our ability to empathize [11]. More recent approaches view mirror

neuron activity as being a sign of rather than a cause of our understanding of others’ intentions and actions. Hence, it is more likely the case that mirror

neuron activity supports our perceptual processes in that simulation makes it easier for us to understand an observed action [12], [13].

Figure 1: Display of emotional interactions as point-lights

Figure 1: Display of emotional interactions as point-lights Figure 1: Display of emotional interactions as point-lights

Figure 1: Display of emotional interactions as point-lights

A. The left-hand figure shows two people interacting as photo or video material. B. The figure on the right shows the same interaction as a point-light display.

Going beyond mirror neurons

To understand another person’s emotional actions, we have to process a large amount of information. Accordingly, it is not just the motor areas of the brain, but also numerous other brain structures that are involved in decoding the host of information on different levels.

Emotional body movements contain, for example, information about the shape, type, speed, and direction of a moving body. To process this information, we use specific areas of the visual cortex that are responsible for processing body shapes [14]. Moreover, information on the intention underlying the movement or the mental state of the moving person also has to be interpreted. One way we do this is by using what is called our mentalization ability. This enables us to attribute mental states such as emotions and intentions to other people. In contrast to simulation, this attribution process is based more on the knowledge we have acquired about the inner states of others [11], and this involves areas of the brain beyond the motor system such as our temporal and frontal lobes [14].

A. Illustration of an exemplary setting that led to activation of mirror neuron areas in the monkey brain. B. Mirror neuron areas in the human brain (IFG = inferior frontal gyrus, PMC = premotor cortex, SMA = supplementary motor area, IPL = inferior parietal lobe, SPL = superior parietal lobe).

Interpersonal differences

Perceiving an emotion-related movement is linked to the automatic activation of our own representation of that movement (i.e., simulation), and therefore this process can differ from person to person. For example, there is experimental evidence that certain parts of the mirror

neuron network are only active if we ourselves possess the ability to perform the observed action. If we are unable to perform it, we may well be able to name and classify the action visually, but we cannot understand it immediately—that is, intuitively [15]. Hence, an intuitive and rapid understanding of the movements we observe and the emotions associated with them also seems to depend on our own motor experiences.

This idea is supported by studies on how observer characteristics influence such perceptual processes. For example, our mood or the ability to perceive our own emotions influences our

perception of others’ emotions [16], [17]. Moreover, people with high emotional expressivity (who express their emotions, both verbally and nonverbally through body language) are better at recognizing emotions portrayed through body movements than people with lower emotional expressivity [3]. This may indicate that we use our own representations of emotional actions and behaviors to understand what we are observing.

Although these findings suggest that a simulation process is involved, they do not confirm this directly. The ability to recognize specific body movements may also be based on a perceptual learning process [18]. In line with this, our perceptual abilities could also be trained through repeated real-life contact with physical expressions of feelings. Even when the type of representation or its form is “new,” our brains can recognize sequences of movements that we already know and thus draw conclusions about their emotional meaning.

Conclusion

We humans are experts in recognizing intentions and emotions from movements. We use characteristic movement information stemming from different body parts to distinguish between and categorize emotional states such as sadness and joy. For example, the speed of an observed body movement plays a central role in this process. In addition, our perception of an emotional movement is influenced by our individual experience, as it is linked to an automatic activation of our own representation of that movement. Hence, the more similar our (motor) experiences are, the greater might be our intuitive understanding of the other person.

Title Image: Михаил Секацкий via Pixabay

Figure 1: Left: Syda Productions via Shutterstock https://www.shutterstock.com/de/image-photo/people-relationship-difficul... License: Standard license from Shutterstock). Right: own image material

Figure 2 was created with BioRender.com.

References

[1] A. Heck, A. Chroust, H. White, R. Jubran, and R. S. Bhatt, “Development of body emotion

perception in infancy: From

discrimination to

recognition,” Infant Behav. Dev., vol. 50, pp. 42–51, 2018.

[2] B. de Gelder, “Towards the neurobiology of emotional body language,” Nat. Rev. Neurosci., vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 242–249, 2006.

[3] J. Bachmann, A. Zabicki, J. Munzert, and B. Krüger, “Emotional expressivity of the observer mediates

recognition of affective states from human body movements,” Cogn. Emot., vol. 34, no. 7, pp. 1370–1381, 2020.

[4] J. Keck, A. Zabicki, J. Bachmann, J. Munzert, and B. Krüger, “Decoding spatiotemporal features of emotional body language in social interactions,” PsyArXiv, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/62uv9

[5] J. Decety and J. A. Sommerville, “Shared representations between self and other: A social cognitive

neuroscience view,” Trends Cogn. Sci., vol. 7, no. 12, pp. 527–533, 2003.

[6] V. Gallese and C. Sinigaglia, “What is so special about embodied simulation?,” Trends Cogn. Sci., vol. 15, no. 11, pp. 512–519, 2011.

[7] G. Rizzolatti, L. Fadiga, V. Gallese, and L. Fogassi, “Premotor cortex and the

recognition of motor actions,” Cogn. Brain Res., vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 131–141, 1996.

[8] G. Buccino et al., “Action observation activates premotor and parietal areas in a somatotopic manner: An

fMRI study,” Eur. J. Neurosci., vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 400–404, 2001.

[9] R. Mukamel, A. D. Ekstrom, J. Kaplan, M. Iacoboni, and I. Fried, “Single-

neuron responses in humans during execution and observation of actions,” Curr. Biol., vol. 20, no. 8, pp. 750–756, 2010.

[10] B. Wicker et al., “Both of us disgusted in my insula: The common neural basis of seeing and

feeling disgust,”

Neuron, vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 655–664, 2003.

[11] C. Lamm and J. Majdandžić, “The role of shared neural activations, mirror neurons, and morality in

empathy: A critical comment,” Neurosci. Res., vol. 90, pp. 15–24, 2015.

[12] G. Csibra, “Action mirroring and action understanding: An alternative account,” in Sensorimotor foundations of higher cognition: Attention and performance XX, P. Haggard, Y. Rossetti, and M. Kawato, Eds. Oxford University Press, pp. 461–479, 2008.

[13] M. Wilson and G. Knoblich, “The case for motor involvement in perceiving conspecifics,” Psychol. Bull., vol. 131, no. 3, p. 460, 2005.

[14] J. Bachmann, J. Munzert, and B. Krüger, “Neural underpinnings of the

perception of emotional states derived from biological human motion: A review of

neuroimaging research,” Front. Psychol., vol. 9, Art. no. 1763, 2018.

[15] G. Rizzolatti and C. Sinigaglia, “The functional role of the parieto-frontal mirror circuit: Interpretations and misinterpretations,” Nat. Rev. Neurosci., vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 264–274, 2010.

[16] B. Lorey et al., “Confidence in emotion

perception in point-light displays varies with the ability to perceive own emotions,” PLoS One, vol. 7, no. 8, Art. no. e42169, 2012.

[17] F. M. Van der Veen, E. A. Evers, N. E. Deutz, and J. A. Schmitt, “Effects of acute tryptophan depletion on mood and facial emotion

perception related brain activation and performance in healthy women with and without a family history of

depression,” Neuropsychopharmacology, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 216–224, 2007.

[18] E. D. Grossman, R. Blake, and C. Y. Kim, “Learning to see biological motion: Brain activity parallels behavior,” J. Cogn. Neurosci., vol. 16, no. 9, pp. 1669–1679, 2004.