How the voice gives away what you are feeling

Reviewers: Dr. Christine Nussbaum, Aisyah Shamshun

People’s tone of voice changes when they are feeling different emotions. This helps people to recognize the feelings of others.

Figure 1. Emotions can be communicated using the voice.

Figure 1. Emotions can be communicated using the voice.

The ability to recognize what other people are

feeling is crucial to understanding how others behave – and what their behavior might be a reaction to. This is important because it can help people to understand or support those close to them. Recognizing others’ emotions can also help people in professional and political contexts. In business negotiations, for example, recognizing the emotions of one's negotiation partner increases the success of the negotiation [1].

One important channel through which emotions are recognized is the voice. Research has shown that individuals are able to tell if a person sounds sad, happy, or angry, even when they ignore the actual meaning of what somebody else is saying [2]. Think about that first moment when a person picks up the phone. Chances are you will quickly recognize what mood the person on the other end of the line is in, even if you cannot see them and, in some cases, have never seen them in your life, simply because you can hear the emotion in their voice. But how are individuals able to accurately infer other people’s emotions merely from their voices? In this article, we describe how the

recognition process takes place, and which

factors influence the accuracy of emotion

recognition from the voice.

How to recognize emotions from the voice

One way of recognizing emotions from another person’s voice is their

tone of voice, that is, the way that the volume, pitch, rhythm, tempo of speech, and voice quality change when a person is speaking [3, 4]. People can recognize a wide range of emotions this way [5]. When looking at the combined evidence from 37 different studies on the

recognition of emotions, researchers showed that people are able to recognize 25 different emotions from the

tone of voice. These emotions include happiness, fear, pride, awe, and lust [5]. In other words, the results suggest that there are patterns in the

tone of voice, which correspond to specific emotions and, therefore, enable people to recognize them.

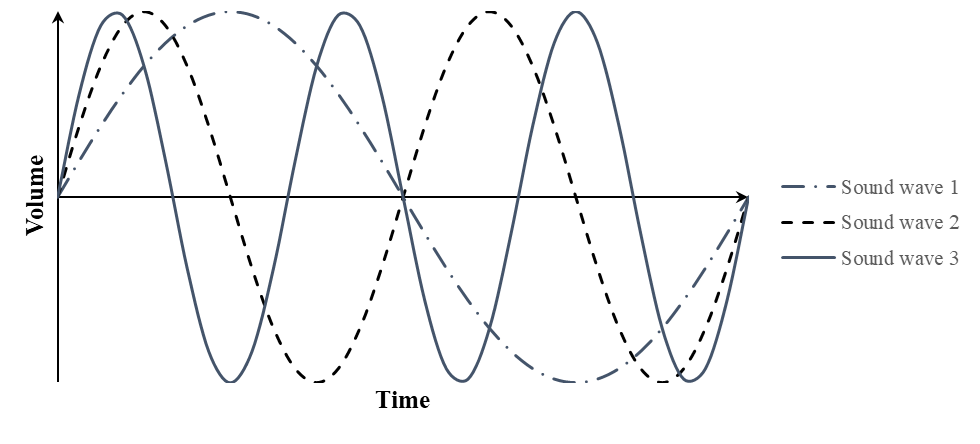

To further identify which emotion corresponds to which voice pattern, researchers have analyzed speech recordings expressing various emotions [6, 7]. Such analyses indicate that people speak louder when they express negative emotions such as anger, despair, or disgust than when expressing positive emotions. When angry, people are, therefore, quite literally raising their voice. Besides volume, the expression of negative emotions is different from positive emotions in terms of frequencies [6]. To understand what this means, it is important to understand the role that frequencies generally play in speech. Essentially, every sound we hear can be described as a vibration of air. However, a single sound does not only consist of one vibration but multiple vibrations occurring at the same time, which all have different frequencies – they differ with respect to how many vibrations occur in a certain amount of time [8] (Figure 2). The more vibrations occur in a given time, the higher the frequency. When we speak, we produce sounds because the air from our lungs produces vibrations at different frequencies. The sounds we produce, including speech, differ in the frequencies they consist of. Frequencies, therefore, also shape the way our voice sounds – and the way that we express negative and positive emotions. People seem to be able to recognize these voice differences between positive and negative emotions, although we might not be able to consciously identify which aspects of the voice make them sound different.

Figure 2. Sound waves with different frequencies. The three sound waves in the figure have the same loudness, but they differ in how many vibrations occur in the same period of time (i.e., they have different frequencies). Sound wave 1 has the lowest frequency, with the fewest vibrations; sound wave 2 has a higher frequency, with more vibrations; and sound wave 3 has the highest frequency, with the most vibrations. If you were to look at a recording of speech in the form of such waves, you would see many more waves of different frequencies layered on top of each other.

Figure 2. Sound waves with different frequencies. The three sound waves in the figure have the same loudness, but they differ in how many vibrations occur in the same period of time (i.e., they have different frequencies). Sound wave 1 has the lowest frequency, with the fewest vibrations; sound wave 2 has a higher frequency, with more vibrations; and sound wave 3 has the highest frequency, with the most vibrations. If you were to look at a recording of speech in the form of such waves, you would see many more waves of different frequencies layered on top of each other.

For identifying positive emotions such as happiness and joy, pitch plays a very important role [7]. Interestingly, pitch allows individuals to differentiate both happy and joyful emotions from neutral ones: happy and joyful emotions are usually higher in pitch than neutral expressions. Besides pitch and volume, speech rate is an important aspect that helps people distinguish different positive emotions from each other. Specifically, the speech rate is higher when people express pride and joy than when they express admiration [7]. Imagine talking to the winner of an Olympic gold medal on the podium. Ask them about their recent achievement, and you might imagine a fast, quite high-pitched recollection of the events leading up to the win. However, if you were to ask them about their idol or the person who inspired them to compete, likely a much slower expression of adoration and admiration would follow.

The circumstances that enable us to accurately infer others’ emotions from the voice

The research reviewed above indicates that people can infer emotions from spoken expressions merely by interpreting the tone of voice. However, how accurately people can actually infer others’ emotions from their voices depends on several factors, such as which emotion is expressed, what language the emotion is expressed in, and the person’s age.

Figure 3. Accuracy of emotion recognition.

Figure 3. Accuracy of emotion recognition.

The influence of different emotions

Although people are generally good at recognizing emotions from the voice, some emotions are more accurately recognized than others. In particular, people recognize negative emotions more accurately than positive emotions [5]. This difference might be due to evolutionary factors [4]. Researchers argue that emotions have evolved because they heightened our ancestors’ chance of survival by promoting specific behaviors in life-threatening circumstances [9, 10]. Explaining the function of emotions in such a way makes a lot of sense for negative emotions. However, positive emotions do not usually arise in life-threatening situations [9]. Hence, one possible reason for negative emotions being easier to recognize from the tone of voice than positive emotions is that their recognition was more crucial for our ancestors’ survival.

Negative emotions are not only recognized more easily than positive ones— there are also more nuanced differences between negative emotions: Anger and sadness, for example, are recognized better than disgust [2, 4]. The reasons for these differences in the accuracy of emotion

recognition are not clear, but researchers have provided some possible explanations [11]. Anger might be particularly easy to recognize from the

tone of voice because it is related to threatening other people. From an evolutionary perspective, it is beneficial to be able to threaten others rather indirectly over large distances, and the voice is ideally suited to do so [11].

While there are some explanations for the advantage of recognizing anger, explaining why sadness is recognized so well compared to other emotions is not so easy. Some researchers argue that the voice pattern for sadness is very unique and can, therefore, be easily distinguished from other emotions [11]. Disgust, on the other hand, might be more difficult to recognize from the

tone of voice because its pattern might be more variable than those of other emotions. Another reason might be that disgust is usually expressed in shorter utterances such as “Yuck!” and not so much through

tone of voice patterns maintained over longer sentences [11].

The influence of language

An interesting question is whether people can infer others’ emotions even if the other person speaks a foreign language. When investigating such questions, it is important to rule out that emotion recognition is not influenced by other aspects of speech, such as the meaning of spoken words. Researchers have, therefore, developed several ways of removing meaning from spoken expressions while maintaining the usual tone of voice. One way to do so is by presenting people with recorded expressions that sound as if they were produced in a certain language, but have no actual meaning in that language. Such speech is called nonsense speech [2].

To test whether people can recognize emotions in foreign languages, an international research team presented Spanish-speaking people with recordings of nonsense speech that mimicked English, German, Arabic, and Spanish expressions. For the recordings, the researchers asked native speakers of the four languages to say different nonsense sentences modeled after their native language in an angry, disgusted, fearful, sad, joyful, or neutral tone of voice. English speakers were, for example, asked to say “The fector egzullin the boshent” in different tones of voice. The researchers then asked people to identify which emotion was expressed in each recording [2]. They showed that it is possible for humans to recognize other people’s emotions from their tone of voice, even when they do not speak the same language.

Although people are able to recognize emotions from sounds that mimic a foreign language, they are usually better at recognizing emotions based on speech patterns that are related to their native language [2, 4]. One possible reason for this is that emotions are expressed slightly differently across languages. Researchers propose that there are certain dialects of emotional expression. This means that expressed emotions can generally be recognized by different groups, but some of the meaning might get lost in the process [5]. For example, a person speaking Scottish English would generally be able to understand someone speaking Australian English but might be unsure what to watch out for when warned about mozzies (mosquitoes). Similarly, a native Croatian speaker might recognize that a Mandarin speaker is sad from their

tone of voice, but certain particularities of the emotional expression might get lost in translation.

Although the assumption that there are dialects of emotional expressions is difficult to test in empirical studies, some researchers came up with promising methods to do so. For example, in one study, researchers trained computer programs to recognize emotional expressions using recordings from Australia, India, Kenya, Singapore, and the United States [12]. The programs were always trained using recordings from one of these cultures. The researchers then tested how well the emotions were recognized from recordings either from the same culture that the program was trained in or a different culture. The emotions were recognized by the computer programs regardless of culture. However, the accuracy of emotion

recognition was higher when the programs were trained and tested on recordings from the same culture.

In another study, the same researchers found that not only computer programs but also people from different cultures show small differences in the aspects of voice patterns they use to express and recognize emotions [13]. When both the person expressing an emotion and the person recognizing the expression are from the same culture, their patterns align more closely than when the two people are from different cultures. In other words, being part of the same culture makes it easier to recognize others’ expressed emotions [5]. These studies support the existence of dialects of emotional expression as an explanation for the advantage of recognizing emotions from one's native language. Both studies show that there are small differences between cultures in how emotions are expressed using the voice. However, these differences are subtle enough that people can still infer expressed emotions in other languages.

The influence of age and development

Another interesting question regarding the recognition of emotions from the voice is whether young children possess this skill already. Knowing whether children are able to recognize emotions from the voice might help us understand whether the ability to recognize emotion from the voice is innate or acquired over a lifetime. Research shows that even infants who are less than a year old already recognize and respond to cues in the tone of voice [14]. This suggests that humans have an innate capacity to recognize emotions from the tone of voice. However, this ability develops with age [4]. That is, adults are more accurate in recognizing emotions from the tone of voice than children and adolescents. This indicates that recognizing emotions from tone of voice is a skill that needs to be learned with age and is only fully developed once people become adults. This also has important consequences for effective communication with children and adolescents. The tone of voice is an important cue for adults when they want to communicate their emotions [15]. However, it might be beneficial to focus on different aspects of communication when you want to communicate emotional states to children and adolescents. Children until the age of 13, for example, focus more on the context of what is being said when inferring others’ emotions than on the tone of voice [15]. Hence, when communicating your emotions to children and adolescents, you might be able to avoid miscommunication by focusing more on the context than on changing your tone of voice.

Summary

Ample research in psychology shows that people can recognize others’ emotions from their tone of voice. This works because specific emotions are associated with specific patterns of pitch, volume, rhythm, voice quality, and tempo of speech. The skill to accurately detect others’ emotions from the voice develops across the lifespan and works best in native languages. Overall, the tone of voice is a powerful tool for communicating emotions to other people. It is important to be aware and considerate of this in conversations, especially as the way in which tone is used to communicate emotions can vary slightly from one language to another.

REFERENCES

[1] P. Staff, “Dear Negotiation Coach: What Hostage Negotiations Can Teach Any Negotiator,” Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School, 05 Jun., 2021. https://www.pon.harvard.edu/daily/business-negotiations/ask-a-negotiatio... (accessed: Mar. 15 2023).

[2] M. D. Pell, L. Monetta, S. Paulmann, and S. A. Kotz, “Recognizing Emotions in a Foreign Language,” J Nonverbal Behav, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 107–120, 2009, doi: 10.1007/s10919-008-0065-7.

[3] R. L. Trask and P. Stockwell, Language and linguistics: The key concepts / R.L. Trask ; edited by Peter Stockwell, 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 2007.

[4] G. Chronaki, M. Wigelsworth, M. D. Pell, and S. A. Kotz, “The development of cross-cultural

recognition of vocal emotion during childhood and adolescence,” Scientific reports, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 8659, 2018, doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26889-1.

[5] P. Laukka and H. A. Elfenbein, “Cross-Cultural Emotion

Recognition and

In-Group Advantage in Vocal Expression: A

Meta-Analysis,” Emotion Review, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 3–11, 2021, doi: 10.1177/1754073919897295.

[6] K. Hammerschmidt and U. Jürgens, “Acoustical correlates of affective prosody,” Journal of voice : official journal of the Voice Foundation, vol. 21, no. 5, pp. 531–540, 2007, doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2006.03.002.

[7] R. G. Kamiloğlu, A. H. Fischer, and D. A. Sauter, “Good vibrations: A review of vocal expressions of positive emotions,” Psychonomic bulletin & review, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 237–265, 2020, doi: 10.3758/s13423-019-01701-x.

[8] B. Pompino-Marschall, Einführung in die Phonetik (De Gruyter Studienbuch): De Gruyter, 2009.

[9] B. L. Fredrickson, “What Good Are Positive Emotions?,” Review of general psychology : journal of Division 1, of the American Psychological Association, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 300–319, 1998, doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.300.

[10] J. Tooby and L. Cosmides, “The past explains the present,” Ethology and Sociobiology, vol. 11, 4-5, pp. 375–424, 1990, doi: 10.1016/0162-3095(90)90017-Z.

[11] T. Johnstone and K. R. Scherer, “Vocal Communication of Emotion,” in Handbook of emotions, M. Lewis and J. M. Haviland-Jones, Eds., 2nd ed., New York: The Guilford Press, 2004.

[12] P. Laukka, D. Neiberg, and H. A. Elfenbein, “Evidence for cultural dialects in vocal emotion expression: acoustic classification within and across five nations,” Emotion (Washington, D.C.), vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 445–449, 2014, doi: 10.1037/a0036048.

[13] P. Laukka et al., “The expression and

recognition of emotions in the voice across five nations: A lens model analysis based on acoustic features,” Journal of personality and social psychology, vol. 111, no. 5, pp. 686–705, 2016, doi: 10.1037/pspi0000066.

[14] M. Morningstar, E. E. Nelson, and M. A. Dirks, “Maturation of vocal emotion

recognition: Insights from the developmental and

neuroimaging literature,”

Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, vol. 90, pp. 221–230, 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.04.019.

[15] M. Aguert, V. Laval, A. Lacroix, S. Gil, and L. Le Bigot, “Inferring emotions from speech prosody: not so easy at age five,” PloS one, vol. 8, no. 12, e83657, 2013, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083657.

Image 1: Gerd Altmann via pixabay.

Image 2: Created by the authors.

Image 3: slightly_different via pixabay.