On the same wavelength—Do parents and children understand each other better if their brains are “in sync”?

Editorial assistants: Elisabeth Höhne and Jana Dreston

Note: An earlier version of this article has been published in the German version of In-Mind.

Humans are social beings by nature. We often (unconsciously) imitate each other’s behaviors—think of yawning or laughing. Recent research shows that this imitation extends even beyond actions; it happens in our brains, too. State-of-the-art neuroimaging techniques reveal that interpersonal neural synchrony, where the brain activities of two or more interacting people align, is important for understanding others, starting from early childhood. In our article, we explore how interpersonal neural synchrony occurs during parent-child interactions and how it relates to behavior, relationship quality, and gender.

From birth, our lives are shaped by social interactions. We cannot survive without them. However, our strong dependence on social interactions goes beyond the first months and years of our lives and extends well into adolescence and adulthood. In fact, studies involving more than 3.5 million adult participants have shown that lower social integration and decreased access to

social support can increase our mortality risk by up to 30%—more so than excessive smoking or alcohol consumption [1, 2]. Social isolation and loneliness are powerful stressors for both the mind and body, raising the likelihood of developing long-term conditions such as Alzheimer’s, heart disease, diabetes, and cancer.

But social interactions are not just about survival; they are vital for development and well-being. Through social interactions—especially with their parents—children learn and practice essential social, cognitive, and emotional skills. These skills, such as understanding others’ intentions, managing emotions, and controlling attention, lay the groundwork for successful social interactions throughout life [3].

Despite the critical role of these early interactions, very little research has examined what exactly happens in children’s and their parents’ brains, for example, during mutual play, problem-solving, or free verbal conversations. Until recently, it was also unclear which neural patterns underlie behavior during parent-child interactions, whether these patterns are related to relationship quality, and whether

gender differences play a role. Nowadays, such questions can be investigated with the help of new

neuroimaging techniques and analysis methods. We can now study two or more brains simultaneously, directly measuring how they synchronize and adapt to one another during interaction.

Mutual attunement in the brain, behavior, and physiology

When we interact with others, we naturally and automatically imitate and adapt to each other’s behavior. This “social contagion” is often seen in simple actions like yawning or laughing. But this tendency to synchronize extends beyond behavior. It can also be observed in our physiology and biology, including

synchrony in heart rhythms and the release of hormones. Recent research has shown that this

synchrony is also present in the brain. When two or more people engage with one another, their brain activities tend to align, or “sync up,” over the course of their interaction. This means we can observe increases and decreases in brain activity happening at roughly the same time and in similar areas across different individuals. This remarkable phenomenon, where behavior, physiological responses, hormone levels, and brain activity align during social interactions, is collectively known as “bio-behavioral synchrony” [4].

Scientists now believe that bio-behavioral

synchrony plays a key role in how we perceive, pay attention to, and react to both social and non-social stimuli [5]. For example, if you are crossing the road and see someone in front of you looking to the left with a fearful facial expression, you are also more likely to look to the left, and thus, recognize a potential danger more quickly. Bio-behavioral

synchrony also strengthens our sense of community and belonging. This, in turn, can lead to more effective

collaboration, social inclusion/integration, and more positive thoughts and actions toward others. In one innovative study, infants were moved up and down in a baby carrier either in or out of

synchrony with an adult experimenter. Children who were moved in sync were subsequently more likely and quicker to show helping behavior toward the adult experimenter [6]. Another study examined the effects of synchronized movement on

prejudice and

stereotypes toward ethnic minorities. Hungarian participants were asked to walk either in sync or out of sync with a member of the Roma community for three minutes. Researchers observed that synchronous walking—where both individuals coordinated their movements—led to a decrease in

prejudice and

stereotypes against the ethnic minority [7]. Given such compelling results, the next question researchers sought to answer was what happens in the brain during social interactions. Could this mutual attunement also be observed at the neural level, particularly between parents and children?

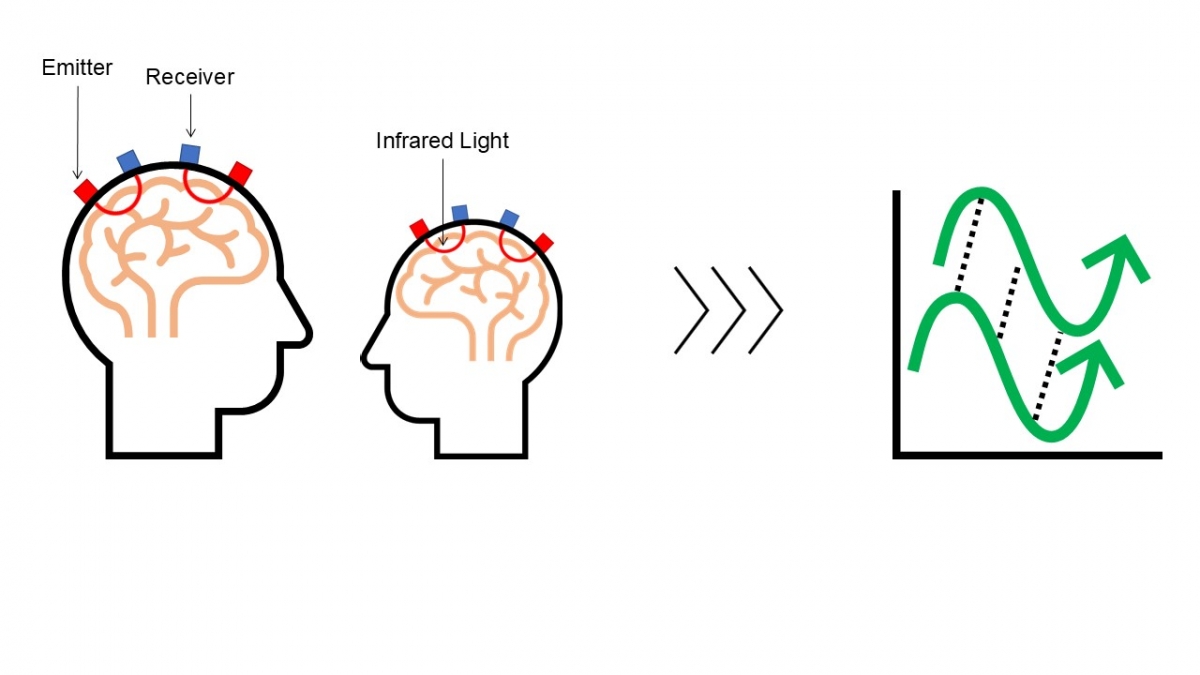

Mutual attunement of brain activity

To assess bio-behavioral

synchrony in brain activity during parent-child interactions,

functional near-infrared spectroscopy (

fNIRS) is particularly suitable. Unlike other

imaging techniques, such as electroencephalography (

EEG) or

functional magnetic resonance imaging (

fMRI),

fNIRS is less sensitive to movement. This makes it ideal for studying interactions in a more natural, real-world setting. When using

fNIRS, infrared light is emitted from sensors placed on the scalp and travels through the outer layers of the brain. As the light passes through, some of it is absorbed, and the rest is detected by a receiver placed on the skull about 3 cm away from the emitter. By measuring how much light is absorbed, we can estimate the concentration of oxygen-saturated hemoglobin in the blood in these outer brain layers. Since increased brain activity requires more oxygen, a higher concentration of oxygenated blood indicates higher levels of brain activity. Using this data, we can calculate the alignment of brain activities between two interacting individuals, creating a measure of interpersonal neural synchrony—the extent to which their brain activity becomes “in sync” during interaction.

Just like radio communication, where the transmitter and the receiver must be on the same wavelength for a signal to get through, current research suggests that the brain waves of interacting individuals also synchronize during social interactions. When this happens, interaction partners often report

feeling more understood and emotionally connected to the other person. This phenomenon, called interpersonal neural

synchrony, likely arises from the simultaneous and recurring activation of groups of neurons—known as oscillators—in both interaction partners. Essentially, the oscillators of the receiver are thought to adapt to the oscillators of the sender [8].

On the same wavelength

Picture 2: Schematic depiction of the fNIRS measurement principle. Left: Emitters (red squares) on the scalp surface emit infrared light (red lines), which is partially absorbed within the outermost layers of the brain and subsequently returns to the scalp surface where it is detected by receivers (blue squares). Right: From the pattern of the received infrared light, the increase and decrease in brain activity (green lines) of the parent and child are first individually determined and then converted into a measure of mutual adaptation of brain activity (dashed black lines).

Picture 2: Schematic depiction of the fNIRS measurement principle. Left: Emitters (red squares) on the scalp surface emit infrared light (red lines), which is partially absorbed within the outermost layers of the brain and subsequently returns to the scalp surface where it is detected by receivers (blue squares). Right: From the pattern of the received infrared light, the increase and decrease in brain activity (green lines) of the parent and child are first individually determined and then converted into a measure of mutual adaptation of brain activity (dashed black lines).

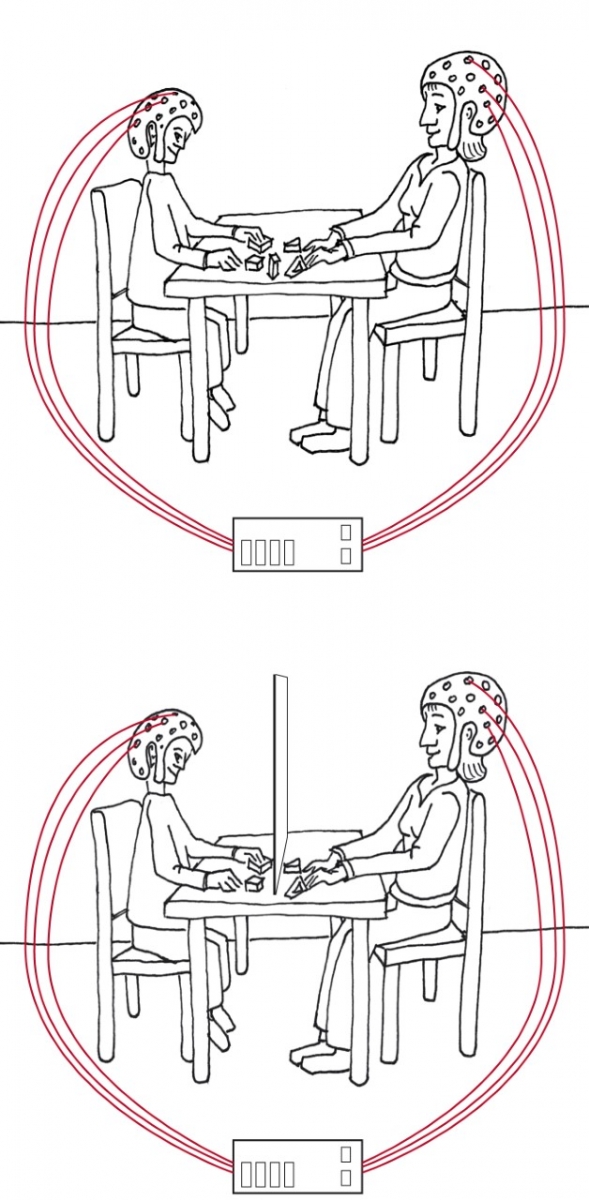

So, what exactly happens in children’s and parents’ brains when they interact? And how are their behaviors and neural patterns related during these interactions? To investigate these questions, parent-child pairs (usually with children of preschool or primary school age) are invited to the laboratory. Once there, they engage in various activities, such as playing games or having conversations. For the game tasks, researchers often use computerized setups or puzzles (see e.g., [9, 10]). Researchers then compare how brain activity synchronizes during interactive, and thus, collaborative tasks versus an

independent task, and sometimes also an additional rest period. For the conversations, parent-child pairs are given several possible topics, such as what they did earlier that day or their plans for the weekend. The

goal is to let a natural conversation unfold. Throughout these activities, brain activities are most often measured in two key regions. One area is overlapping with the temporo-parietal junction, which is involved in understanding others’ intentions, and another area is overlapping with the dorsolateral frontal cortex, which is linked to attention and voluntary control.

Now, what do these studies reveal? Parent-child pairs exhibit synchronized brain activities, especially when working together to solve problems. This

synchrony is much stronger during collaborative tasks than when they solve problems individually or are simply “resting.” In many cases, there is also a correlation between interpersonal neural

synchrony and

cooperation success. In other words, the higher the interpersonal neural

synchrony during a joint computer game or puzzle, the more effectively they appear to work together (e.g., [10, 11]). In addition, synchronization of brain activity increases the longer the parent and child engage in conversation, especially when they take turns speaking [12]. This increase in

synchrony tends to occur in brain regions involved in understanding others’ intentions, predicting actions, taking different perspectives, and maintaining attention. Scientists therefore assume that interpersonal neural

synchrony may be related to our behavior and our understanding of others’ goals and intentions during social interactions [5].

Differences in mutual attunement of brain activity

Picture 3: Schematic depiction of a typical fNIRS experiment to measure the mutual adaptation of brain activity in parent-child pairs. Top: Solving puzzles together. Bottom: Solving puzzles independently.

Picture 3: Schematic depiction of a typical fNIRS experiment to measure the mutual adaptation of brain activity in parent-child pairs. Top: Solving puzzles together. Bottom: Solving puzzles independently.

We have seen that joint problem-solving and free verbal conversation are linked to a general increase in interpersonal neural

synchrony in parent-child pairs. But does this level of interpersonal neural

synchrony remain the same for all parent-child pairs, or are there differences? Recent research suggests that the extent of interpersonal neural

synchrony is related to both the quality of the parent-child relationship and the

gender of the parent and child.

So, how do scientists determine the relationship between interpersonal neural

synchrony and parent-child relationship quality? One approach is based on

attachment theory.

Attachment theory suggests that better relationship quality is associated with sensitive, emotionally supportive parental behavior toward the child. Known as parental sensitivity, such behavior is characterized by swift, appropriate responses to children’s cues while encouraging a child’s

autonomy, supporting their independence and initiative. Behavioral indicators of relationship quality, such as parental sensitivity, can be observed in video recordings of parent-child interactions from the above-mentioned studies. For example, in mother-child pairs working together to solve puzzles, higher interpersonal neural

synchrony was linked to greater behavioral reciprocity, such as taking turns and allowing the child more

autonomy. Both of these behaviors point to increased maternal sensitivity [10].

Attachment theory offers another way to assess the quality of the parent-child relationship, using age-appropriate self-reports and semi-structured interviews with both parents and children. The core idea is that relationship patterns, formed through early interactions with caregivers, are stored in

memory and influence later behavior.

In a study on interpersonal neural

synchrony between mothers and their 8- to 12-year-old children, children’s

attachment representations of their mothers were determined using an

attachment self-report questionnaire and then linked to the mutual attunement of mother-child brain activities during a computerized interaction game. Researchers observed that interpersonal neural

synchrony was somewhat weaker during collaborative gameplay when children reported higher insecure-avoidant

attachment representations with their mothers [9].

Another study assessed both children’s and parents’

attachment representations using semi-structured interviews and associated the outcomes with interpersonal neural

synchrony during collaborative puzzle play [13]. Interestingly, researchers found that interpersonal neural

synchrony was higher in mother-child pairs where mothers had more insecure (versus secure)

attachment representations. These combined findings suggest a complex relationship between interpersonal neural

synchrony and

attachment. They indicate that this link can take different shapes, with insecure

attachment representations being associated with both lower and higher interpersonal neural

synchrony. In other words, more

synchrony is not always a sign of better relationship quality—it may sometimes also signal difficulties in interaction. Future research is needed to explore this idea further.

In addition to relationship quality, children’s and parents’

gender also appears to play a role in interpersonal neural

synchrony. For example, researchers observed a correlation between interpersonal neural

synchrony and behavioral reciprocity (i.e., more turn-taking) during collaborative puzzle play in mother-child pairs but not in father-child pairs [10, 11]. Other research found that father-child pairs showed higher interpersonal neural

synchrony during collaborative puzzle solving compared to mother-child pairs, while behavioral reciprocity was lower in father-child compared to mother-child pairs [13]. These differences may reflect distinct behavioral and mental mechanisms when mothers and fathers interact with their children. Previous studies suggest that mother-child interactions are somewhat more rhythmic and structured, while father-child interactions are considered more energetic and playful [4, 14]. The same is likely true for interactions between children and grandparents, friends, teachers, and others, although such differences have not yet been systematically studied. The higher interpersonal neural

synchrony observed in father-child pairs during puzzle tasks may also reflect the fact that fathers and children have less practice with more structured activities like puzzles. As a result, they may need to rely more heavily on mutual prediction and attentional regulation to collaborate effectively, resulting in higher levels of interpersonal neural

synchrony. Overall, these findings highlight the benefits of children interacting with a variety of adults. Each type of interaction helps children develop different social, emotional, and cognitive skills, contributing to well-rounded development.

Conclusion

With the help of new neuroimaging techniques such as fNIRS hyperscanning, we can nowadays explore what happens in children’s and parents’ brains when they collaboratively solve a task or freely talk to one another. The currently available data suggest that parents and children understand each other better when their brains are more “in sync”. However, the level of interpersonal neural synchrony can vary depending on factors like relationship quality and gender, and higher synchrony does not always associate with better outcomes. Researchers are hopeful that these insights will soon translate into practical applications, such as enhancing education in schools or improving therapy and counseling approaches, ultimately promoting families’ emotional well-being and mental health.

References

[1] J. Holt-Lunstad, T. B. Smith, and J. B. Layton, “Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-

analytic review,” PLoS Med., vol. 7, no. 7, e1000316, 2010, doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

[2] J. Holt-Lunstad, T. B. Smith, M. Baker, T. Harris, and D. Stephenson, “Loneliness and social isolation as risk

factors for mortality: A meta-

analytic review,” Perspect. Psych. Sci., vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 227–237, 2015, doi: 10.1177/1745691614568352

[3] R. Feldman, “Parent-infant

synchrony: A biobehavioral model of mutual influences in the formation of affiliative bonds,” Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev., vol. 77, no. 2, pp. 42–51, 2012, doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2011.00660.x

[4] R. Feldman, “The neurobiology of human attachments,” Trends Cogn. Sci., vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 80–99, 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2016.11.007

[5] S. Hoehl, M. Fairhurst, and A. Schirmer, “Interactional

synchrony: Signals, mechanisms and benefits,” Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci., vol. 16, no. 1-2, pp. 5–18, 2020, doi: 10.1093/scan/nsaa024

[6] L. K. Cirelli, K. M. Einarson, and L. J. Trainor, “Interpersonal

synchrony increases

prosocial behavior in infants,” Dev. Sci., vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 1003–1011, 2014, doi: 10.1111/desc.12193

[7] G. Atherton, N. Sebanz, and L. Cross, “Imagine all the

synchrony: The effects of actual and imagined synchronous walking on attitudes towards marginalised groups,” PLoS One, vol. 14, no. 5, e0216585, 2019, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216585

[8] M. Wilson, and T. P. Wilson, “An oscillator model of the timing of turn-taking,” Psychon. Bull. Rev., vol. 12, no. 6, pp. 957–968, 2005, doi: 10.3758/BF03206432

[9] J. G. Miller et al., “Inter-brain

synchrony in mother-child dyads during

cooperation: An

fNIRS hyperscanning study,” Neuropsychologia, vol. 124, pp. 117–124, 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2018.12.021

[10] T. Nguyen, H. Schleihauf, E. Kayhan, D. Matthes, P. Vrtička, and S. Hoehl, “The effects of interaction quality on neural

synchrony during mother-child problem solving,” Cortex, vol. 124, pp. 235–249, 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2019.11.020

[11] T. Nguyen, H. Schleihauf, M. T. Kungl, E. Kayhan, S. Hoehl, and P. Vrtička, “Interpersonal neurobehavioral

synchrony during father-child problem solving: An

fNIRS hyperscanning study,” Child Dev., vol. 92, no. 4, e565–e580, 2021, doi: 10.1111/cdev.13510

[12] T. Nguyen, H. Schleihauf, E. Kayhan, D. Matthes, P. Vrtička, and S. Hoehl, “Neural

synchrony in mother–child conversation: Exploring the role of conversation patterns,” Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci., vol. 16, no. 1-2, pp. 93–102, 2020, doi: 10.1093/scan/nsaa079

[13] T. Nguyen, M. T. Kungl, S. Hoehl, L. O. White, and P. Vrtička, P, “Visualizing the invisible tie: Linking parent-child neural

synchrony to parents’ and children’s

attachment representations,” Dev. Sci., vol. 26, no. 6, e13504, 2024, doi: 10.1111/desc.13504

[14] R. Feldman, “Infant-mother and infant-father

synchrony: The coregulation of positive

arousal,” Infant Ment. Health J., vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 1–23, 2003, doi: 10.1002/imhj.10041