If you read this…

… you can already do a lot! Reading is a bit like magic: You can easily read a word like “dozibrofu” out loud, even though you’ve probably never seen it before. You can also read a sentence in which the wrods suddnely look copmleteyl dfferent. And even when something isn’t fully described in a text, you can often visualize it clearly. Maybe that’s why you’ve already guessed that we’re about to explain how reading works.

Editorial Assistant: Elisabeth Höhne and Elena Benini.

Note: An earlier version of this article has been published in the German version of In-Mind.

Figure 1. The magic of reading

Figure 1. The magic of reading

The magic of reading

You come across words, sentences, and texts almost everywhere you look. Every day, you read street names, labels on cereal boxes, instructions for games, and sometimes even entire letters and books with ease. But here’s the magic: Words are made up of just a few dots and lines. To understand these dots and lines as letters, words, sentences, and texts, you need a variety of skills [1].

These skills are a bit like magical powers: for example, you can recognize words quickly—even if you’ve never seen them before. You can read whole sentences quite fluently, even when the ltetres are mxeid up. You can also use your imagination to create images in your mind from a text, even if the text doesn’t describe them in detail. All these magical powers—recognizing words, reading sentences, and understanding texts—come together to make what we call “reading.”

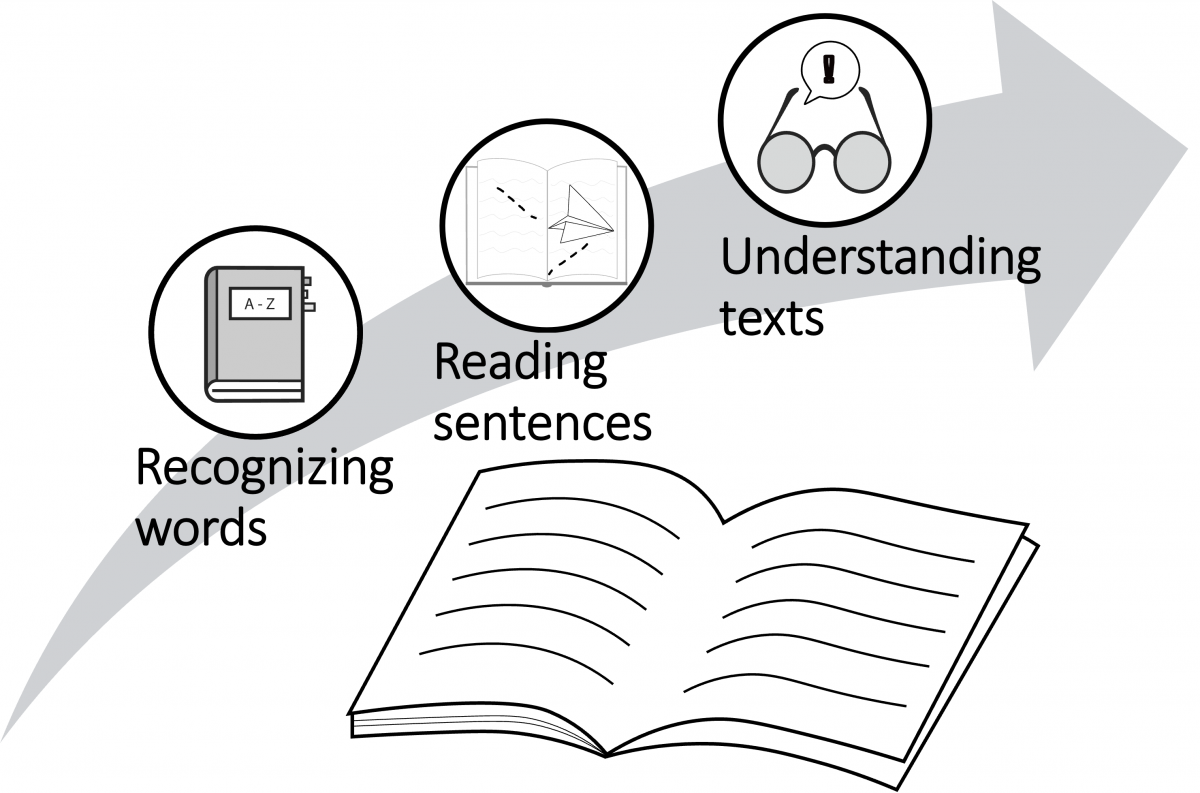

Figure 2. How different magical powers work together when reading

Figure 2. How different magical powers work together when reading

In this article, we explain what happens in your brain when you use these magical powers and how they all work together when you read.

Magical power : recognizing words

The first magical power your brain has related to reading is recognizing words. When you read words, lots of things happen at the same time. First, you imagine in your head how the letters sound in spoken language. Even though letters are just a few dots and lines, you’ve learned what sounds letters make. The letter “T” can be written t, T, T , T, or t, and you’ll still know how to pronounce it in the words tone, aunt, T eacher, or rat. Your brain puts these single letters together to form syllables, and then it combines these syllables to form whole words. For experienced readers, this happens automatically and extremely quickly. Try looking at the following word without reading it: king. That’s not possible, is it? As readers, we’ve learned to recognize familiar words “at a glance” [2]. This is possible if the word’s written form is stored as an image in your brain. For such an image to form in your brain, you must’ve read the word many times before. As a result, an image of the word is then stored in your brain in a kind of dictionary. Finally, your brain can access this image, and you can recognize the word within milliseconds. At this point, you no longer identify each letter one by one but recognize the whole word at once.

This is more difficult for your brain with unfamiliar words. For example, try to read the following word: dozibrofu. When you read an unfamiliar word like this, your brain takes a detour. It has to divide the whole word back into its syllables and reads them one by one (do-zi-bro-fu). This process takes a little longer. Because you’ve learned how to pronounce each letter in English, you can also read a made-up word like “dozibrofu” by sounding it out, syllable by syllable. By combining the sounds, you can then read the word as a whole. This magical power allows you to read any word—whether it makes sense or is completely made-up. Perhaps you remember how exhausting it used to be to read each word letter by letter. Now that you recognize words as whole units more often, reading has become much easier. As experienced readers, we can recognize familiar words quickly and automatically. However, we can also read unfamiliar ones by combining the sounds of individual letters and syllables into a whole word.

Magical power : reading sentences

Recognizing words quickly is necessary for the second magical power: reading sentences fluently. You do this by combining small components (single words) to form larger components (whole sentences). We know how this works thanks to experiments that observed people’s eye movements while they were reading [3]. These studies showed that we don’t read word by word, one after another. Instead, our eyes make rapid, jerky movements—sometimes jumping forward, sometimes backward. Sometimes we make short stops, sometimes we even skip words. You can try this yourself. Ask someone to read a text to you and watch their eyes as they do it. You’ll notice that their eyes keep jumping back and forth as they read. By focusing on important words and skipping unimportant ones, experienced readers can read between 200 and 300 words per minute [4]. The more we practice reading, the faster can read whole sentences. Even if the lteters aer sudndely revsered, you’ll only hvea a few problems. Did you notice the missing word in the sentence above? If not, that’s because your brain no longer focuses on single letters. Instead, it recognizes whole words and uses them to form sentences. This fluent reading of sentences helps you to focus more on the meaning of what you’re reading and to understand texts.

Magical power : understanding texts

Reading is more than recognizing words quickly and reading sentences fluently. Above all, reading means understanding what someone else’s written. When we read texts, we can get information that someone else’ has made available to us: We can talk to each other through the text. To do this, we, as readers, must develop our own images of the content and draw conclusions. For example, read this short story:

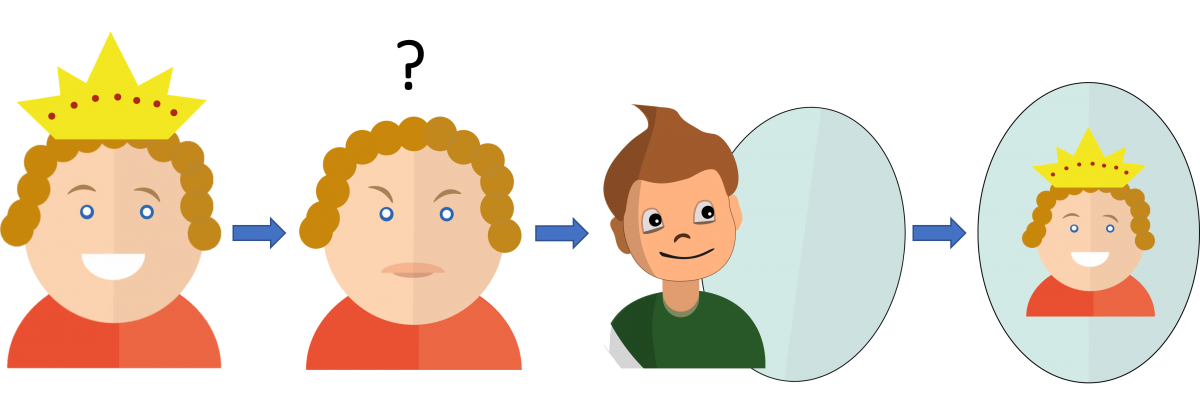

Every morning, King Neko proudly puts on his crown. But today, he couldn’t find it. King Neko called his servant. He grinned and brought the king a mirror.

You probably understand right away that King Neko wants his crown back. You understand that he asks his servant for help. You also understand that the servant (and not King Neko) is the one who grins. And even though the story doesn’t say it, you understand that King Neko’s been wearing his crown all along. This is what’s meant by “reading between the lines.” It means you can figure out things that aren’t said directly. We almost always “read between the lines” when we try to understand a text. When we read, we form images in our minds, and these images help us understand the story better. These mental images are called “mental representations” [5]. As we read, our mental images change and grow. At first, you might imagine a king happily putting on his crown. Then, you picture the king without his crown. Ultimately, when the servant brings him a mirror, you realize that the king must’ve been wearing his crown the whole time. He’s probably happy about this because he’s found his crown again. These mental images help you understand the story better and show how our brain keeps adding new ideas as we read.

Figure 3. Mental representations grow as you read

Figure 3. Mental representations grow as you read

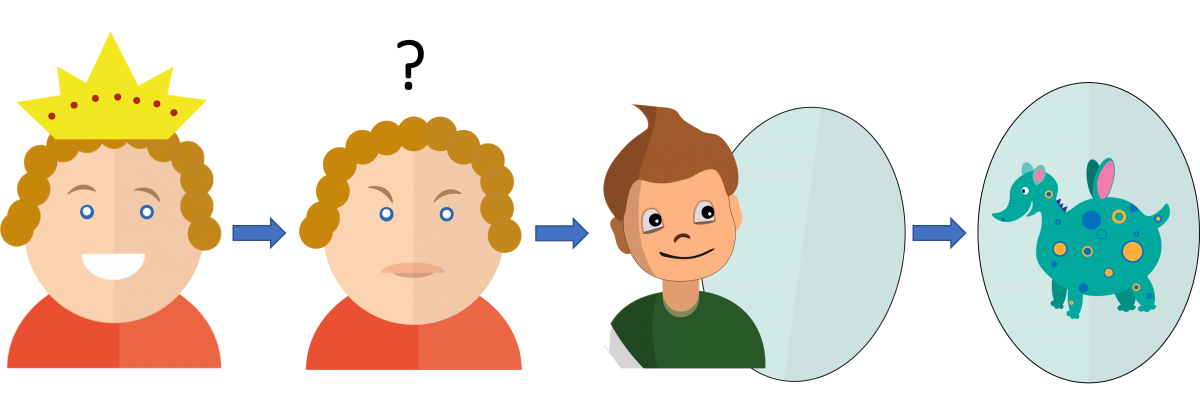

The images we create in our minds when we read can be different for each person, and these images depend on what we already know about the topic. For example, if you don’t know what “mental representations” means, you might not understand why people’s images in their minds can be different, or why the pictures depend on what they already know. In such cases, a reader can use strategies to better understand the text. A reader can look up difficult words like “mental representations” in a dictionary, search for them online, ask someone else, or try to guess what they mean from the sentences around them. Sometimes, we might need to go back and reread parts of the text to make the ideas clearer. In this text, for example, we can read in the paragraph above that “mental representations” are the images we form in our minds as we read. Even though these mental images can differ from person to person, they still need to be connected to the story. Your own images shouldn’t stray too far from the information in the text. Otherwise, we’d invent our own story and no longer learn what someone actually wanted to say in a text. For example, if we read our short story and imagine that King Neko sees a green, spotted, winged animal in the mirror that stole his crown, this is probably not what the author wanted to tell us with the text.

Figure 4. Mental representations should stay close to the text

Figure 4. Mental representations should stay close to the text

Let’s summarize: To understand what we read, we create so-called mental representations. These images help us put the information together and read between the lines. As we read, we use what we already know and the clues that the text gives us to make these images more detailed and clearer.

If you read this … you can already do a lot

Reading isn’t an easy task for your brain. We often don’t even realize how much our brain does when we read. It has to recognize letters, syllables, and words. It has to read sentences fluently. And it has to understand texts, even if they don’t contain all the information we actually need. Many things happen at the same time while reading. All these magical powers make reading so special: When you read, you can recreate, in your own mind, thoughts that someone else’s written down in a different place and at a different time. For example, everything we’ve written down for you in this text—in December 2024 in the city of Münster in Germany—you can read and think about at any time and in any place. You can then use this information and apply it to new situations. For example, after reading this text, you can ask yourself: “What do I know about the process of reading now? What do I want to remember? What else do I want to know?.

And now you can go on with reading and explore many other texts on your own.

Bibliography

[1] A. Gold, Lesen kann man lernen (Reading can be learned). Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2018.

[2] M. Coltheart, “Modeling reading: The dual-route approach,” in The Science of Reading: A Handbook, M. J. Snowling and C. Hulme, Eds., Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing, 2005, pp. 6–23.

[3] K. Rayner and S. A. Duffy, “Lexical complexity and fixation times in reading: Effects of word frequency, verb complexity, and lexical ambiguity,” Mem. Cog., vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 191–201, May 1986, doi: 10.3758/BF03197692.

[4] S. Dehaene, Lesen (Reading). Munich, Germany: Knaus, 2012.

[5] W. Kintsch, “The representation of knowledge in minds and machines”, Int. J. Psychol., vol. 33, no. 6, pp. 411–420, Dec. 1998, doi: 10.1080/002075998400169.

Figures Sources

Figure 1: © Pixabay

Figure 2: cc-by-nc4.0 Arbeitseinheit Diagnostik und Evaluation im schulischen Kontext / Universität Münster

Figure 3: cc-by-nc4.0 Arbeitseinheit Diagnostik und Evaluation im schulischen Kontext / Universität Münster

Figure 4: cc-by-nc4.0 Arbeitseinheit Diagnostik und Evaluation im schulischen Kontext / Universität Münster