Turning disagreements into opportunities: How couples can grow through constructive communication

Reviewers: Martina Grunenberg and Eri Sasaki

Editorial Assistant: Elena Benini.

What if every argument could bring new understanding and growth in your relationship? Explore how conflicts, when handled constructively, can strengthen your bond. Backed by research and filled with actionable insights, this article shows you how to turn tension into trust and disagreements into deeper understanding.

1. Why Conflict Matters

Conflict is a natural part of any relationship. Whether it’s about dividing household chores, managing finances, or addressing deeper emotional needs: Disagreements are inevitable. Yet, the way couples handle conflict can make the difference between a relationship that flourishes and one that falters. In this article, we’ll explore what research says about the role of conflict in relationships and how communication patterns affect relationship quality. Finally, we present practical tools that can help couples turn disagreements into opportunities for growth.

2. Understanding Conflict in Relationships

2.1 Conflict as a Catalyst for Growth

In Western culture, there is a common belief that perfect relationships are free from conflict, where partners glide through life in harmonious agreement. But real relationships are much more textured. Disagreements and tensions are not just unavoidable – they’re necessary. They allow partners to express their individuality, articulate their needs, and understand each other more deeply. Without these moments of friction, a partner can feel distant or detached, like an elusive presence slipping away. A lack of open disagreement can sometimes mean that one partner consistently suppresses their own needs or yields to the other’s wishes – which may foster disconnection and emotional distance over time.

What truly defines a strong relationship and romantic love isn’t the absence of conflict but the presence of repair. Healthy relationships thrive on trust – the belief that, even in the face of disagreements, your partner has your best interests at heart. This trust and sense of safety lay the groundwork for navigating conflicts with resilience, turning moments of tension into opportunities for a deeper connection.

2.2 Why Miscommunication Escalates Conflict

Conflict arises because no two people are exactly alike. Disagreements occur when partners hold different opinions, needs, or interests. These differences are natural and can enrich a relationship, adding depth and passion, but they also require careful navigation. A conflict often arises not simply from the difference itself but when one partner experiences the difference as problematic – for instance when the other’s opinion feels like a violation of shared norms or when personal needs and desires are not being met. Miscommunication frequently amplifies these situations, as what one person says isn’t always what the other hears.

For instance, a comment like, “The sink is full of dishes,” might seem like a simple observation, but depending on the context, it could be received as criticism, frustration, or even a plea for help. When such messages are repeatedly misinterpreted or left unaddressed, this can lead to a growing emotional disconnect between partners – a sense of drifting apart or no longer feeling seen and understood by the other. This emotional distancing often intensifies under stress or in moments of heightened emotional tension.

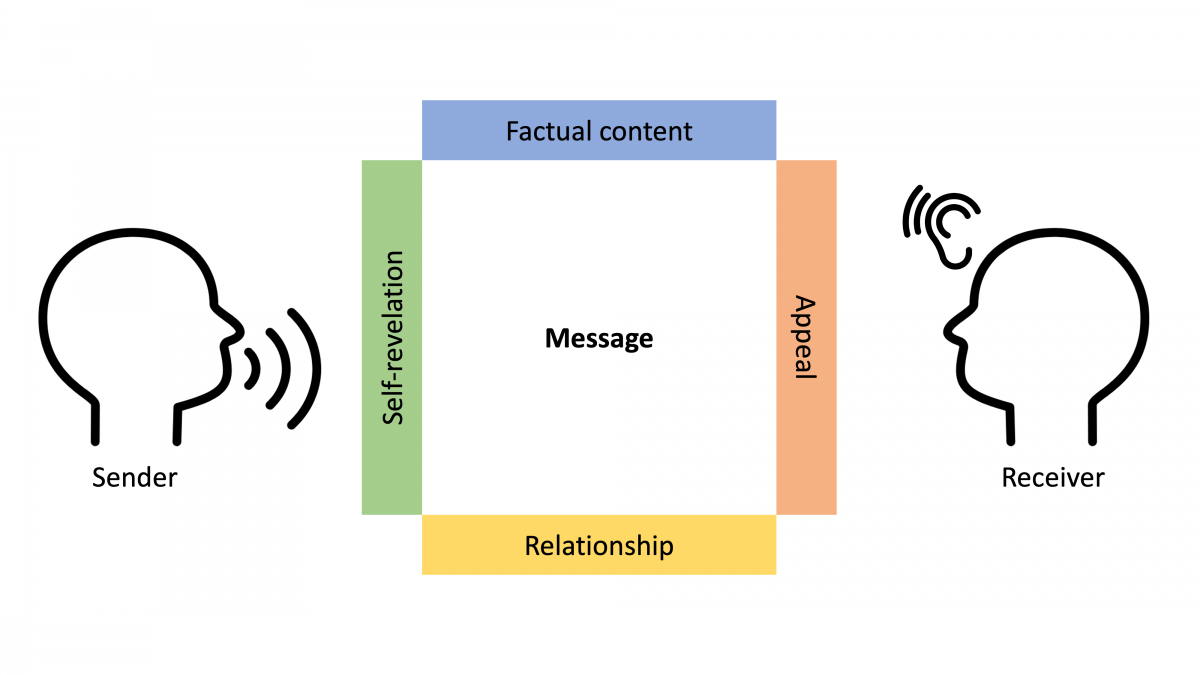

2.3 From Blame to Clarity: The Four-Sides Model

To better understand how miscommunication occurs, the Four-Sides Model of Communication by Friedemann Schulz von Thun offers a valuable framework. Every message, according to this model, has four layers [1]:

- The Factual Level: The straightforward information being shared.

- The Self-Revealing Level: What the speaker shares about themselves.

- The Relationship Level: What the speaker conveys about their view of the relationship.

- The Appeal Level: What the speaker wants the listener to do.

Picture 3. : The Four-Sides Model of Communication by Friedemann Schulz von Thun

Picture 3. : The Four-Sides Model of Communication by Friedemann Schulz von Thun

Take, for example, the statement: “You never listen to me.” On the factual level, it may refer to specific situations in which one partner felt unheard. On the self-revealing level, it might express frustration or hurt, reflecting an unmet emotional need such as wanting to feel acknowledged or valued. On the relationship level, the speaker might be implying a sense of emotional disconnection. And on the appeal level, they are likely asking for more attentive and engaged communication.

Miscommunication often arises when the listener hears only one of these layers or interprets it differently. For instance, they might hear the statement purely as a criticism or attack, rather than as a call for connection.

A more constructive approach would be for the speaker to rephrase their concern in a way that invites understanding rather than placing blame. Instead of saying, “You never listen to me,” they might ask, “What did you hear me say?” or share “I feel like we’ve lost track - can we just take a moment and clarify what the main point is again?” This kind of reframing shifts the tone of the conversation. Rather than accusing the partner of not listening, the speaker invites clarification and reflection. This small but powerful change in communication can defuse tension, prevent escalation, and build a bridge toward greater connection.

2.4 Reframing Intentions: Positive Assumptions in Conflict

In addition to understanding how messages can be (mis)understood, another key shift is how we interpret our partner’s intentions during conflict. One of the most powerful mindset shifts in handling conflict is learning to assume that your partner’s intentions are not hostile. It’s easy to perceive a sharp tone or a thoughtless comment as an attack. But more often than not, these moments are clumsy attempts to express deeper feelings – like fear, sadness, or the need to feel seen. Assuming positive intent doesn’t mean ignoring hurtful behavior. Rather, it means giving your partner the benefit of the doubt and asking yourself, what might they really be feeling right now?

This shift in perspective helps partners respond with curiosity instead of defensiveness. It opens the door to empathy, making it easier to ask open questions and stay emotionally connected – even in tense moments. In this kind of environment, constructive dialogue can take root, and conflict becomes less about winning and more about understanding [2].

Closely related to this mindset is the idea that conflict shouldn’t be approached as a battle. Many people treat arguments like contests, trying to prove their point or protect their position. But this only deepens the divide. A more productive approach is to view the disagreement as a shared knot to untangle. Instead of pulling in opposite directions, partners can ask: How can we work through this together? This shift – from adversaries to allies –reinforces trust and helps couples move forward with a stronger sense of connection.

In this mindset, conflicts are no longer treated as zero-sum games where one must win and the other must lose. Instead, couples can look for shared, “win-win” solutions – a principle widely supported by relationship research [3].

3. What Does Research Reveal About How Couples Handle Stress and Conflict

3.1 Coping Together Beats Fighting Alone

Stress doesn’t just affect your mood – it shapes how you talk, react, and even argue with your partner. A study by Bodenmann and colleagues [4] surveyed over 300 adults in long-term relationships and found that stress was strongly linked to verbal aggression, especially when anger ran high. But here’s the twist: couples who faced stress together – by listening, supporting, and solving problems as a team – were far less likely to lash out. This kind of dyadic coping turned tension into teamwork [4], [5], [6].

3.2 Talking About Stress Makes You Stronger

When life gets tough, many couples fall silent – and that silence can be costly. In a study with 345 couples, Ledermann and colleagues [7] showed that external stress (like job pressure) increased relationship strain, which in turn made conflict conversations more difficult. Poor communication drove down satisfaction – but couples who talked openly about stress broke this chain reaction. In other words: sharing your worries protects your connection.

3.3 The Spiral You Want to Avoid

How couples argue can be more important than what they argue about. Psychologist Kurt Hahlweg [8] observed real-life couple conflicts and found a clear difference: satisfied couples resolved fights in just a few conversational turns. Dissatisfied couples? They spiralled – getting stuck in long, reactive exchanges where negativity triggered even more negativity. Once you’re in that loop, it’s hard to get out.

3.4 One Size Doesn’t Fit All

What helps one couple might backfire for another. A study by Ross and colleagues [9] found that even seemingly harmful conflict patterns – like one partner demanding while the other withdraws – can have different meanings depending on context. For some low-income couples, for instance, withdrawing served as a way to prevent escalation rather than avoid the issue. The key takeaway? Relationship advice must be tailored to real life. Culture, socioeconomic status, and stress levels shape how couples communicate and cope. It is important to remember that every relationship is unique, and what works well for one couple may be less effective for another. Ideally, communication strategies should be adapted to the couple’s specific lived reality, and in many cases, professional support can help tailor these tools to meet their needs and circumstances.

4. Tools for Constructive Conflict Resolution

Picture 4. Fostering Connection

Picture 4. Fostering Connection

Understanding the dynamics of conflict is essential, but applying practical tools to navigate these moments is where true growth begins. This section focuses on actionable strategies couples can use to strengthen their relationships during disagreements, turning potential pitfalls into opportunities for connection.

4.1 Breaking the Negative Spiral

One of the most common challenges couples face is breaking free from negative communication patterns. As research by Kurt Hahlweg [8] revealed, dissatisfied couples often engage in prolonged cycles of criticism and defensiveness, trapping them in a “negative spiral”. The key to escaping these patterns lies in interrupting the flow of negativity and fostering constructive dialogue.

A powerful technique is to use clarifying questions during conflict. For example:

- “That didn’t feel good. What was your intention?”

This question helps clarify the underlying intent behind a potentially hurtful comment, shifting the focus from accusation to understanding. - “I’m

feeling defensive. Can you share that another way?”

By expressing vulnerability and requesting a different approach, this question creates space for constructive communication. - “When you said that, I thought you meant [explain what you heard]. Can you clarify?”

This question addresses potential miscommunication, inviting the other person to explain their words and intentions.

These questions help defuse tension, allowing both partners to step back, reflect, and re-engage with empathy. By focusing on the underlying emotions and intentions behind words, couples can redirect conflicts toward resolution.

4.2 The Rogerian Argument: A Framework for Productive Conflict

An effective method for navigating disagreements is the Rogerian argument technique, inspired by the principles of psychotherapist Carl Rogers. This approach emphasizes mutual understanding before resolution [10]. Here’s how it works:

Each partner takes turns expressing their thoughts or feelings.

Before responding, the listener must repeat what they heard, ensuring the speaker feels accurately understood.

Once the speaker confirms their feelings have been captured correctly, the roles switch and the listener becomes the speaker.

For instance, imagine a disagreement over spending habits. Partner A might express frustration about unexpected purchases. Partner B paraphrases: “You feel anxious when I spend money without discussing it first.” When Partner A agrees, they switch roles, allowing Partner B to explain their perspective. This process reduces misunderstandings and ensures both partners feel heard, creating an environment of respect and collaboration through perspective-taking.

4.3 If-Then Plans: Preparing for Hot Moments

Despite our best intentions, staying calm during a heated argument can feel impossible. Emotions often override rational thought, leading to reactions we later regret. A practical way to prepare for these moments is by developing If-Then plans [11]:

- If my partner criticizes me and I feel defensive,

- Then I will take a deep breath and say, “I’m feeling hurt. Can we talk about this calmly?”

These plans act as mental shortcuts, enabling thoughtful responses even in emotionally charged situations. Over time, If-Then plans become automatic, helping couples break destructive patterns and replace them with constructive behaviors [12]. This strengthens self-regulation and can develop into an important coping mechanism in the long term.

As a first step, it can be helpful for each partner to develop these plans individually. This allows for self-reflection and supports emotional self-care, especially in moments when space and boundaries are needed. In the second step, couples can choose to share and co-create If-Then strategies together. This collaborative approach can foster mutual understanding and lay the groundwork for shared solutions in recurring conflict situations.

4.4 Repairing After Conflict: The Post-Conflict Conversation

Conflict resolution doesn’t end when the argument stops. A post-conflict conversation is vital for repairing emotional damage and preventing resentment [13]. This conversation includes four key steps:

- Explain oneself: Calmly share your feelings and perspective without assigning blame.

- Apologize and reconcile: Acknowledge hurtful actions and express genuine regret.

- Compromise: Show a willingness to meet your partner halfway.

- Find solutions together: Collaborate on actionable steps to address the issue and prevent similar conflicts in the future.

4.5 The Role of Individual Reflection in Conflict Resolution

Another essential aspect during or after a conflict is each partner’s ability to manage their own tensions. Taking the time to reflect and clarify personal needs is crucial for navigating disagreements constructively. In these moments, the focus should not be on trying to “fix” the other person but rather on understanding one’s own emotions and needs.

For instance, imagine one partner feels increasingly irritated during an argument because they perceive their concerns are being dismissed. Instead of immediately expressing this as blame – e.g., “You never listen to me!” – they might pause, take a short break and reflect: Why is this bothering me so much? They may realize the irritation stems not from the current topic but from a deeper, unmet need to feel taken seriously. This insight allows them to re-engage the conversation by saying, “I noticed I got upset earlier – I think I was feeling unheard, and that’s something that really matters to me.”

Without this kind of self-awareness, couples risk falling into repetitive negative patterns that are increasingly difficult to escape. But when partners are able to check in with themselves – even briefly – and identify what’s really going on emotionally, it becomes easier to re-enter the dialogue with clarity and calm. By prioritizing individual clarity, partners lay the groundwork for more honest and productive communication. This doesn’t just help resolve the immediate disagreement – it also builds trust and commitment over time, creating space for deeper mutual understanding.

5. Integration: From Conflict to Connection

By integrating techniques like clarifying questions, the Rogerian argument, and If-Then plans, couples can navigate disagreements with greater ease and understanding. These tools empower partners to approach conflicts not as battles to be won but as opportunities to deepen their connection and build a resilient relationship foundation.

6. Summary: Conflict as a Pathway to Growth

Picture 5. Walking forward together – even when the path isn’t straight

Picture 5. Walking forward together – even when the path isn’t straight

Conflict doesn’t have to be a sign of trouble in a relationship. When managed constructively, disagreements become opportunities for deeper understanding, trust, and connection. The key lies in shifting focus from “winning” arguments to unravelling their deeper meaning. By approaching conflict as a shared challenge rather than a competition, couples can strengthen their bond and navigate challenges more effectively. Effectively managing healthy conflict is a vital competence that every relationship should cultivate.

7. Key Takeaways

- The Power of Repair: Every relationship experiences moments of tension. The strength of a partnership lies in how quickly and effectively these moments are repaired. Trust, empathy, and a willingness to listen are essential for rebuilding connections.

- Clarity in Communication: Misunderstandings are inevitable, but they don’t have to escalate. Asking reflective follow-up questions like “What did you hear me say?” can help clarify intentions, reduce defensiveness and support mutual understanding.

- Practical Conflict Strategies: Structured approaches like the Rogerian argument and If-Then plans equip couples with tools to address disagreements constructively. These methods emphasize mutual understanding and thoughtful responses, reducing the risk of harm during conflicts.

- Shared Coping: Dyadic coping, where partners tackle stress together, fosters resilience and satisfaction. Small changes in how couples handle stress and support each other can lead to lasting improvements in their relationship.

- Post-Conflict Healing: Following up after a disagreement with meaningful dialogue helps repair emotional wounds, rebuild trust, and solidify the partnership.

8. Take Action Today

Every couple has the capacity to turn conflict into connection. Start small. Choose one tool – whether it’s asking clarifying questions, practicing an If-Then plan, or trying the Rogerian argument – and use it in your next disagreement. This is an important step towards autonomy and self-efficacy. Growth isn’t about perfection; it’s about progress.

Relationships are not defined by the absence of conflict but by the way partners approach and resolve their disagreements. By embracing the psychological resources and perspectives shared in this article, couples can create a foundation of trust and resilience, transforming disagreements into opportunities for lasting intimacy and growth.

Bibliography

[1] Schulz von Thun, F. (2008). Six Tools for Clear Communication. The Hamburg Approach in English Language. Schulz von Thun Institut für Kommunikation.

[2] Gottman, J., & Gottman, J. M. (2015). 10 Principles for Doing Effective Couples Therapy. W. W. Norton & Company, Incorporated.

[3] Gottman, J., & Silver, N. (2015). The Seven Principles for Making Marriage Work: A Practical Guide from the Country’s Foremost Relationship Expert. Harmony.

[4] Bodenmann, G., Meuwly, N., Bradbury, T. N., Gmelch, S., & Ledermann, T. (2010). Stress, anger, and verbal aggression in intimate relationships: Moderating effects of individual and dyadic coping. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27(3), 408–424. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407510361616

[5] Bodenmann, G. (2005). Dyadic Coping and Its Significance for Marital Functioning. In G. Bodenmann, K. Kayser, & T. A. Revenson (Eds.), Couples coping with stress: Emerging perspectives on dyadic coping (pp. 33–49). American Psychological Association.

[6] Bodenmann, G. (1997). Dyadic coping: A systemic-transactional view of stress and coping among couples: Theory and empirical findings. European Review of Applied Psychology, 47, 137–141.

[7] Ledermann, T., Bodenmann, G., Rudaz, M., & Bradbury, T. N. (2010). Stress, Communication, and Marital Quality in Couples. Family Relations, 59(2), 195–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2010.00595.x

[8] Hahlweg, K. (1986). Partnerschaftliche Interaktion: Empirische Untersuchungen zur Analyse und Modifikation von Beziehungsstörungen. Röttger.

[9] Ross, J. M., Karney, B. R., Nguyen, T. P., & Bradbury, T. N. (2019). Communication that is maladaptive for middle-class couples is adaptive for socioeconomically disadvantaged couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 116(4), 582–597. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000158

[10] Young, R. E., Becker, A. L., & Pike, K. L. (1970). Rhetoric: Discovery and change. Harcourt, Brace & World.

[11] Bieleke, M., Keller, L., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2021). If-then planning. European Review of Social Psychology, 32(1), 88–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2020.1808936

[12] Hallam, G. P., Webb, T. L., Sheeran, P., Miles, E., Wilkinson, I. D., Hunter, M. D., Barker, A. T., Woodruff, P. W. R., Totterdell, P., Lindquist, K. A., & Farrow, T. F. D. (2015). The Neural Correlates of Emotion Regulation by Implementation Intentions. PLOS ONE, 10(3), e0119500. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0119500

[13] Gottman, J. M., & Gottman, J. (2023). Fight right: The five secrets of couples who transform conflict into connection. Harmony.

Figures Sources

PICTURE 1: Priscilla Du Preez via Unsplash https://unsplash.com/de/fotos/person-in-schwarzem-langarmhemd-mit-weissem-keramikbecher-xM4wUnvbCKk

PICTURE 2: Alex Green via Pexels https://www.pexels.com/de-de/foto/afroamerikanerpaar-das-konflikt-in-der-kuche-hat-5699691/

PICTURE 3: Created by the authors using The Noun Project - (CC BY 3.0). Created by Zach Bogart and New River

PICTURE 4: alllessandro_ via Pixabay https://pixabay.com/photos/lovers-meadow-portrait-outdoors-7258617/

PICTURE 5: PICNIC-Foto via Pixabay https://pixabay.com/photos/elderly-couple-walking-trail-2914879/