Learning styles: Why they don't exist but still persist

It is a common

myth that for optimal learning, individual learning styles should be identified and specifically supported. This might include identifying someone as a visual learner and designing the learning environment based on this. Yet, scientific findings clearly show that aligning learning environments with learning styles has no beneficial effects. Why does this

myth persist and what can we do about it?

There is a German version of this article available

Promoting and supporting learning in the best possible way is a central concern at school, at work and in many other areas of life. The high importance of learning conditions was highlighted during the Covid pandemic. Across all professions and age groups, learning was instrumental in successfully meeting new challenges. Practitioners and researchers have been searching for ways to support individual learning for decades. Forbes published an article with 15 suggestions for cost-effectively enhancing learning through technology (Forbes Technology Council, 2022). In the first place, the article states that individual learning styles should be identified and supported in a targeted manner. This proposes that people should be divided into visual, auditory and haptic learners, for example, and should learn most effectively via the corresponding channels. A "visual learner" is described as someone who is better able to memorize information if it is illustrated graphically, for example in the form of diagrams, sketches or illustrations. This seems to be a catchy insight that is also taken up extensively by many practitioners, in particular because the concept of learning styles makes sense in an intuitive way. After all, people are different from each other. A recent literature review of 37 studies involving over 15,000 educators found that, on average, 89.1% of respondents believe that instructional methods should match the learning styles of their students, and that teachers should adapt their instruction to these to a similar degree (Netwon & Salvi, 2020).

Scientifically speaking, there is nothing to learning styles. It is instead a widespread

myth in our society. The scientific findings from numerous studies on the subject clearly show that there is no such thing as learning styles, and that designing learning environments based on supposed styles has no beneficial effects on learning (Aslaksen & Lorås, 2018; Pashler et al., 2008). So why does this

myth persist nonetheless, and what can we do about it? To answer these questions, we first explain what is meant by learning styles, what the scientific findings say about them, and why learning styles already do not make sense from a theoretical perspective.

What is meant by the concept of learning styles?

Individuals differ in their aptitudes and abilities and prefer different learning activities. To do justice to this, the concept of learning styles was developed. In his book "Thinking, Learning, Forgetting" published in 1975, Frederic Vester proposed four types of learners who acquire knowledge differently. He distinguished between auditory (see auditory learning style), visual (see visual learning style), haptic (see haptic learning style), as well as cognitive learners. In more recent literature, a communicative learning style is often listed as the fourth learning style in addition to visual, auditory, and haptic (e.g., Neuburger, 2009).

Figure 1: Overview of four frequently distinguished learning styles

Figure 1: Overview of four frequently distinguished learning styles

The following characteristics are attributed to people who are assigned to the respective learning style: Auditory learners are said to be people who learn by listening and speaking. For them, oral explanations are said to be particularly helpful. In contrast, the visual learner style learns through observation and benefits particularly from graphics, diagrams and pictures in which information is presented. Visual learners would also rather read texts than listen to content. Characteristic of the haptic learning style is learning by touching and

feeling as well as practical experience and practice. Finally, the communicative learner type is said to benefit especially from conversations, discussions, and interactive exchange (Looß, 2001; Neuburger, 2009). The "cognitive learning style" originally proposed by Vester is described by the latter as someone who learns through the intellect. Logically, this learning style does not fit with the others; after all, intellectual performance is also present when learning with auditory, visual, and haptic information.

According to the concept of learning styles, information should be presented in such a way that it can be absorbed through the respective preferred channel of

perception in order to make learning as effective as possible (Kirschner & van Merriënboer, 2013). In this regard, it is indeed scientifically confirmed that individuals differ in their cognitive abilities. The cognitive ability to take in information through different sensory channels differs among individuals, as does the ability to perform individual cognitive processes. Addressing these individual differences in learning requirements is useful in facilitating successful learning. In contrast, "learning styles" categorize individuals based on how they absorb knowledge rather than how well they do so (Willingham, Hughes & Dobolyi, 2015). The assumption of the learning styles concept is that learners' individual preferences for particular sensory channels are

independent of their cognitive abilities and

independent of learning content, which have

significant implications for the design of learning processes. From this, teachers should create different instructional materials for high-quality instruction. That means that it is not about matching the topic, prior knowledge, or motivations of the students, but instead doing justice to the different "learning styles" of the students.

What does the research say: Are there individual "learning styles"?

In learning situations, students usually prefer certain learning methods. When asked what type of learner they are, most have a clear answer: some report that they prefer to learn with visual materials, others swear by auditory processes. This self-assessment is often based on the

perception of personal preferences. The reasons for this, in addition to the learning content, typically lie in personality as well as assessments and feelings at the time they are being asked (Looß, 2001). These partly very changeable influencing variables imply that individual preferences for different learning paths are not constant, which already contradicts a classification of persons into individual learning styles. Furthermore, a preferred way of presenting information (e.g., visually) can often be attributed to the fact that the learner prefers tasks in which the person has a high level of

competence and hopes for success.

Preferences are usually also dependent on the subject. For example, imagine you were told "I want to teach you something. Would you rather learn it by watching a slide-show presentation on it, by reading a text on it, or by listening to it as an audio recording?". Can you answer this question just like that, or would you like to first ask what exactly it is that you are being asked to learn? The concept of learning styles, however, assumes that individuals choose individual learning channels and learn better with these than with others - regardless of what content they are learning. The consideration of individual learning styles therefore already fails in the attempt to reliably categorize learners accordingly and to assign them individual learning styles. Nevertheless, questionnaires and category schemes are repeatedly used to make such classifications (e.g., Neuburger, 2009).

"Learning styles" are therefore not

independent of individual abilities and the respective learning content. But what about the main argument of representatives of the concept of learning styles?

What does the research say: Does taking individual "learning styles" into account make a difference?

As a reminder, the main argument for learning styles is that the respective styles should learn better via their respective "learning channels" than via other channels. For example, visual learners should learn better with visual information than with auditory or haptic information. If learners have a strong style preference, their learning performance should improve if the delivery of content is adapted to the respective learning style. Without experimental findings in this regard, the concept of learning styles would leave nothing more than the basic insight that different learners have different interests, backgrounds, and abilities.

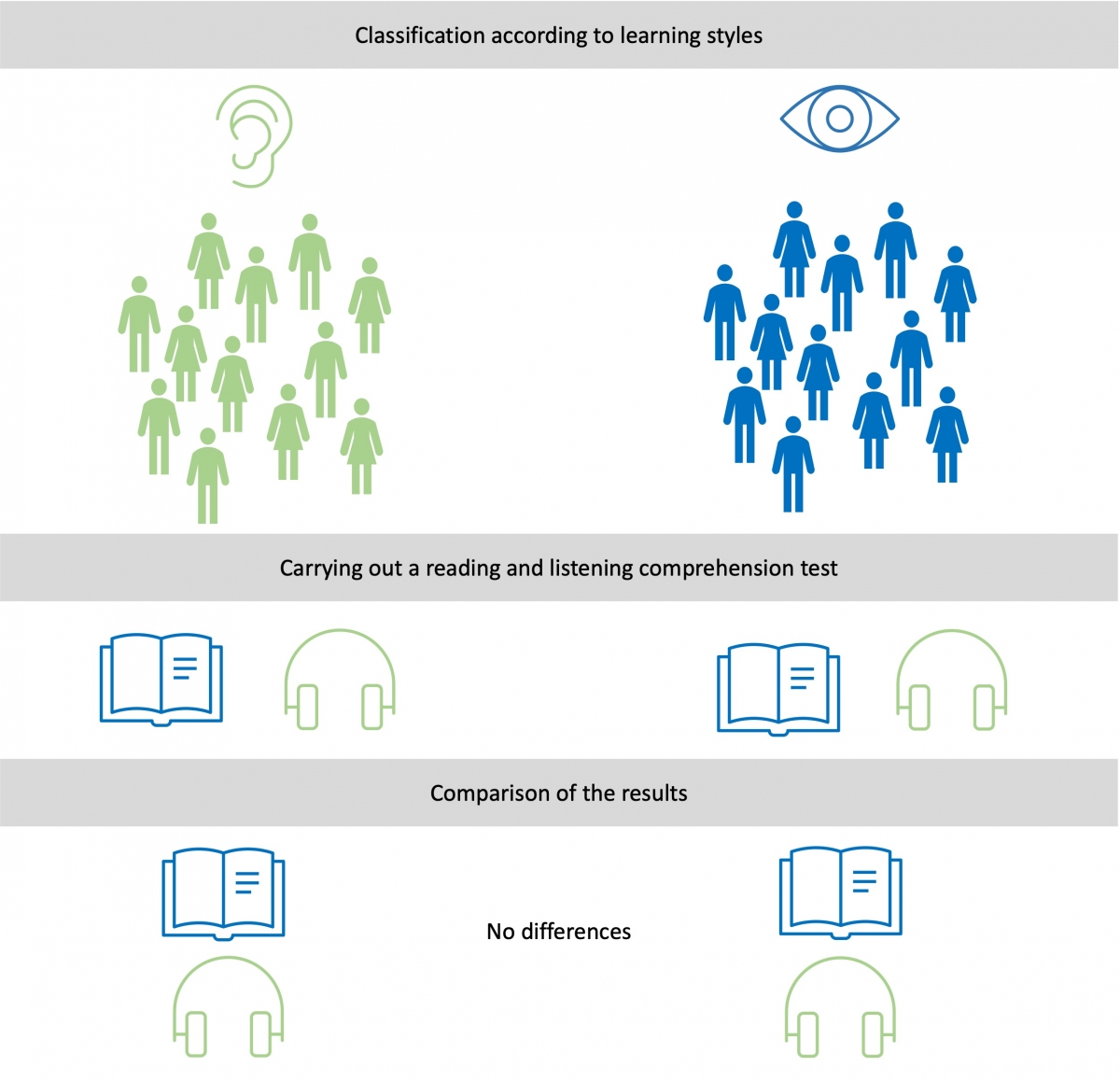

Numerous recent literature reviews clearly demonstrate that there is no robust evidence that matching instructional methods to the assumed learning styles of individual students would improve their learning performance (Aslaksen & Lorås, 2018; Pashler et al., 2008). In fact, there are numerous carefully controlled experiments in which the relevant assumption has been tested. As an example, we can consider a study by Rogowsky et al. (2015). Participants in the study were assigned to either an auditory or a visual learning style using an established questionnaire. Both groups were given a knowledge test in both verbal and written form. The results showed that no relationship could be determined between learning style and ability to complete listening comprehension tasks or reading comprehension tasks. For a second experiment, the participants were randomly divided into two groups. One group received information in the form of an audio book, the other group in the form of a written text. The information did not differ in content. In the following written knowledge tests, that were carried out both immediately after the presentation and after a time interval of two weeks, no evidence was found for a relationship between the learning style and the matching teaching method. In other words, learners did not learn better if the method matched their learning style.

Figure 2: Visualization of the study by Rogowsky et al. (2015) on the missing effects of supposed learning styles

Figure 2: Visualization of the study by Rogowsky et al. (2015) on the missing effects of supposed learning styles

In addition to these findings, research also points to the fact that identifying one's presumed learning style does not influence the preferences individuals report for different learning methods and the ways in which they choose to learn (Husmann & O'Loughlin, 2018; Lopa & Wray, 2015).

The empirical findings speak a clear language: Aligning the learning environment according to the individual preferences of the learners does not offer any advantages. But are learning styles even a theory with a solid theoretical basis? Here, too, the answer is clear: No. From a psychological perspective, the learning style concept has three central deficits, which are explained below.

Theoretical problems relating to the concept of learning styles

1. Preferences are not equal to consistent traits

An observation in a particular learning situation (e.g., "I can remember this particular fact best via a chart") does not at all allow the conclusion of a persistent characteristic of a person

independent of learning situation and learning object. The so-called consistency paradox shows that we intuitively judge our own and others' behavior to be very consistent over time, but the correlation between behaviors at different points in time is in fact very low (Heckhausen, 1989). Attempts to divide persons into types have been and continue to be popular outside of science (and especially in esotericism); however, psychological research shows that most human traits do not take the form of distinct categories, but rather each person has a different expression on each of these traits. For example, people cannot be meaningfully divided into different personality types, but are better distinguished on the basis of the manifestations of relevant personality traits (such as

conscientiousness or

agreeableness). The same applies to learning: Individuals cannot be assigned to specific types or styles, but each have a characteristic profile on different dimensions.

2. Learning is not equal to

perception

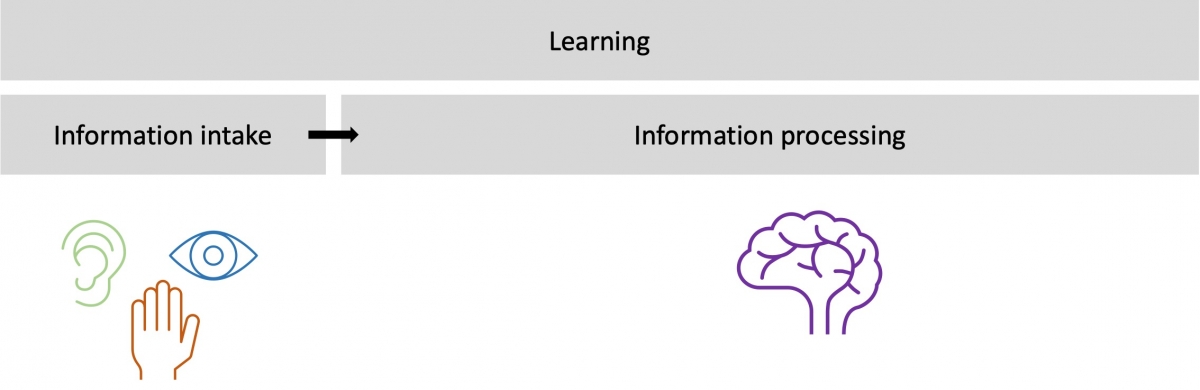

Learning style concepts that differentiate according to sensory channels assume the naïve notion that learning is synonymous with the reception of information via the sensory organs. However, an important finding of cognitive psychology is that most of the

memory content is stored completely independently of any sensory modality (Willingham, 2005). One exception is perceptual

memory, in which stimuli, among other things, are stored independently of conscious verbalizations. However, this is primarily used for recognizing these same stimuli and has no

significant role in knowledge or skill acquisition. Learning is to the most part not the intake of information, but their processing. "It is not the senses that decide whether events or occurrences in the environment are registered, processed, connectable for our thinking and acting and thus become meaningful" (Kahlert, 2007, p. 1).

Figure 3: Learning in the process of information intake and processing

Figure 3: Learning in the process of information intake and processing

Whether information passes from short-term

memory to long-term

memory depends on how much it is elaborated. Elaboration means linking new information with existing knowledge structures. The decisive factor for learning is which operations the brain performs with the content. For example, how often it is repeated or how much existing content it can be linked to. It is not the channel of input information that is decisive for effective learning, but cognitive conditions such as different talents, different levels of development and prior knowledge, and different levels of motivation.

3. Learning is not the same as remembering

The third central misunderstanding of the learning style concept lies in the equation of the terms 'learning' and 'remembering something'. Information—an image, a sequence of letters, a sequence of sounds, or a sensory sensation—can be recorded and stored in

memory both visually, auditorily, or haptically. But even if individuals had a preferred or even actually superior channel for this, this would say very little about the best way they learn, as learning goes beyond memorization. It involves understanding, grasping meaning, and solving problems. All these cognitive processes are based on changes in structures in the brain.

Memory is involved in every learning process as a

memory instance - no matter whether new behaviors, new knowledge, new competencies, or new problem-solving skills are created. However, the decisive processes do not occur during information intake, but during information processing. Whether something is learned effectively depends on multiple contexts in which the new information is embedded (Weinstein, 1978).

But does it hurt to use learning styles when designing learning environments?

Of course, one could say that learning styles

don't help, but at least they wouldn't hurt either. However, it is quite problematic to categorize learners on the basis of their supposed sensory preferences. First, they may develop false theories about themselves and their learning behaviors that ultimately limit them in their learning (Vasquez, 2009). Second, learners may unjustly be placed in a particular category and demotivated because of their assignment to a learning style. For example, a student who is classified as an "auditory learner" may conclude that studying visual subjects such as a painting is pointless for her. Third, the time teachers put into designing learning-style appropriate instructions comes at the expense of time for meaningful measures of individualization. Following the concept of learning styles, teachers would ideally have to create four or more versions of their instructional materials to match the learning styles of their students. Fourth, it is contradictory for teachers to teach their students to think critically, but not to apply this thinking in their own teaching. The persistent belief in learning styles weakens the credibility of educators and creates unjustified and unrealistic educational expectations.

References

Appel, M. (2020). Wie lässt sich das Postfaktische eindämmen?. In M. Appel. (Hrsg.), Die Psychologie des Postfaktischen (S. 205-210). Springer.

Forbes Technology Council (24.01.2022). 15 low-cost, high-impact ways to improve educational outcomes through technology. https://www.forbes.com/sites/unicefusa/2022/03/24/a-volunteer-translator...

Heckhausen, H. (1989). Motivation und Handeln. Springer.

Husmann, P. R., & O'Loughlin, V. D. (2019). Another nail in the coffin for learning styles? Disparities among undergraduate anatomy students’ study strategies, class performance, and reported VARK learning styles. Anatomical Sciences Education, 12(1), 6–19.

Kahlert, J. (2000). Ganzheitlich lernen mit allen Sinnen? Plädoyer für einen Abschied von unergiebigen Begriffen. Grundschulmagazin, 12, 37-40.

Kirschner, P. A., & van Merriënboer, J. J. (2013). Do learners really know best? Urban legends in education. Educational Psychologist, 48(3), 169–183.

Looß, M. (2001). Lerntypen. Die Deutsche Schule, 93(2), 186–198.

La Lopa, J. M., & Wray, M. L. (2015).

Debunking the matching hypothesis of learning style theorists in hospitality education. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education, 27(3), 120–128.

Neuburger, R. (2009). Lernblockaden bewältigen: Entspannung lernen und Leistung steigern. Compact Verlag.

Newton, P. M., & Salvi, A. (2020). How common is belief in the learning styles neuromyth, and does it matter? A pragmatic systematic review. Frontiers in Education. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.602451

Pashler, H., McDaniel, M., Rohrer, D., & Bjork, R. (2008). Learning styles: Concepts and evidence. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 9(3), 105–119.

Rogowsky, B. A., Calhoun, B. M., & Tallal, P. (2015). Matching learning style to instructional method: Effects on comprehension. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(1), 64–78.

Vester, F., Vester, F., Vester, F., Biochemist, P., Vester, F., & Biochimiste, P. (1975). Denken, Lernen, Vergessen: was geht in unserem Kopf vor, wie lernt das Gehirn, und wann läßt es uns im Stich? Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt.

Vasquez, K. (2009). Learning styles as self-fulfilling prophecies. In R. Gurung, & L. Prieto (Hrsg.), Getting culture: Incorporating diversity across the curriculum (pp. 53–63). Stylus.

Weinstein, C. (1978). Elaboration skills as a learning strategy. In H. O’Neil (Hrsg.), Learning strategies (pp. 31–55). Academic Press.

Willingham, D. T., Hughes, E. M., & Dobolyi, D. G. (2015). The scientific status of learning styles theories. Teaching of Psychology, 42(3), 266–271.

Figures

Figure 1: Property of the authors

Figure 2: Property of the authors

Figure 3: Property of the authors