Plant-based, insect-based, or cultivated meat alternatives—Why do we (not) consume them?

Editorial Assistants: Lorenz Grolig and Maren Giersiepen.

Note: An earlier version of this article has been published in the German version of In-Mind.

Meat alternatives have become a fixture on supermarket shelves. While people have been consuming plant-based alternatives for a long time, the consumption of insects and, in the future, cultivated meat faces major challenges. What factors drive people to consume meat alternatives? And why do many people still find it so difficult to replace meat in their diet? Personal values, product perceptions, and social influence play decisive roles in our food choices, especially when it comes to replacing familiar products with alternatives. In this article, we thus examine the psychological factors that promote or hinder the consumption of meat alternatives, as well as the barriers that still need to be overcome.

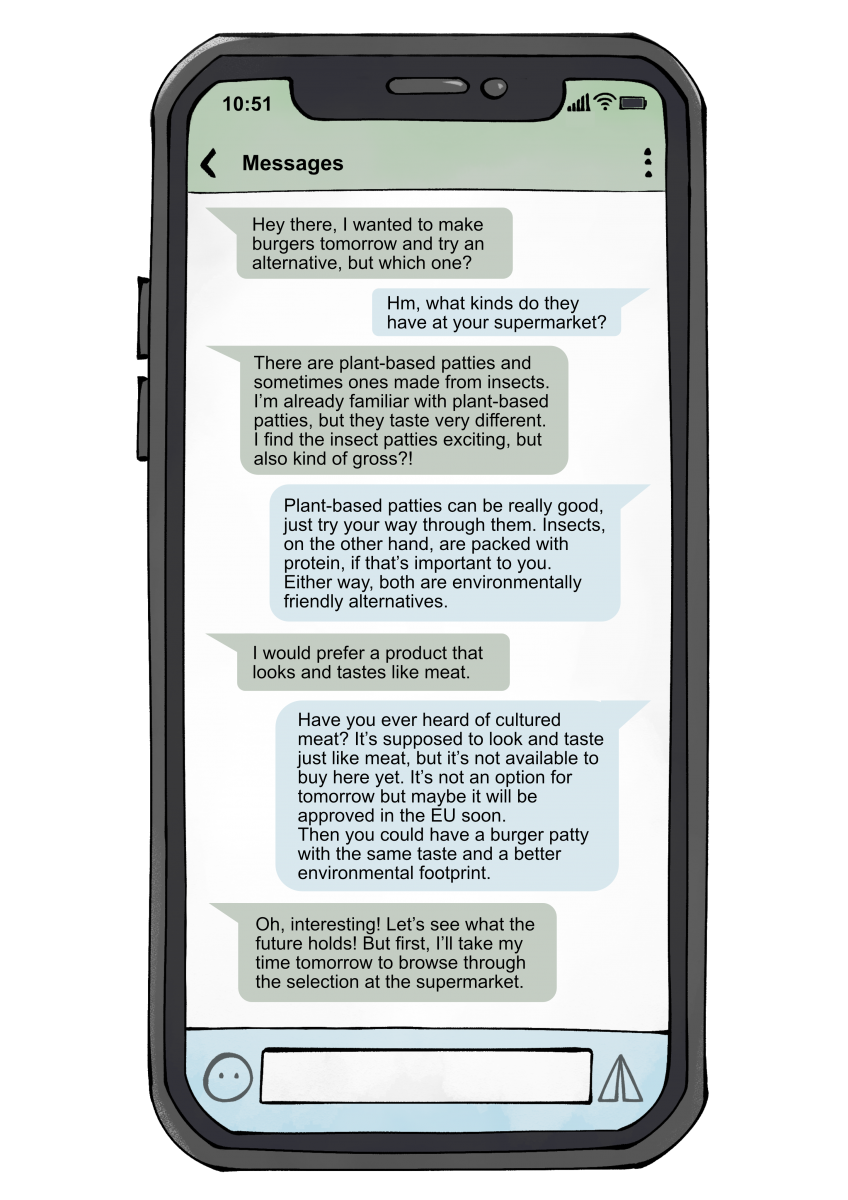

Figure 1: Potential scenario for a future visit to the supermarket

Figure 1: Potential scenario for a future visit to the supermarket

Have you ever tried a veggie burger, dared to try an insect burger, or even considered eating lab-grown meat? Many people find it difficult to eliminate meat from their diet. Why is that? The decision to either eat meat or deliberately avoid it is often complex. Psychological factors play a major role in this decision. Social traditions and enjoyment motivate people to consume meat, while concerns about health, animal welfare, and sustainability lead people to abstain from eating meat [1]. Even though many people care about animal welfare and know that animals must die if they wish to eat meat, people continue to eat it. People have developed strategies to ignore the moral consequences of their meat consumption, known as the “meat paradox” [2], [3]. A detailed discussion of the meat paradox can be found in the In-Mind article by Buttlar and Walther [3].

Meat alternatives come in many forms, including cutlets, burgers, and cold cuts; a walk through almost any supermarket shows that these have become an indispensable part of the product range. Basically, meat substitutes are meant to be similar to conventional meat products in their appearance, texture, and taste. Plant-based meat alternatives are often made from soy or wheat protein. Examples of traditional plant-based meat alternatives include tofu and tempeh (soy-based) and seitan (wheat-based). These were not originally developed to imitate meat; they are products in their own right. However, there are also processed alternatives made from legumes such as peas or lentils. Depending on cultivation and processing, the production of plant-based meat alternatives often produces only one-third of the greenhouse gases produced during the processing of chicken meat; this difference is even more pronounced for pork and beef [4].

A few years ago, it was also possible to buy insect-based alternative products, such as burger patties made from finely ground insects, in German supermarkets. After the first insect species were approved as food on the EU market in 2021, the number of approved species has been steadily increasing. If a burger patty contains ground insects, this must be indicated on the packaging by stating the Latin and English names of the insect species and specifying the form in which it is processed [5]. Insects are not considered a “classic” meat substitute because, when unprocessed, they do not resemble meat in either appearance or taste. Rather, insects are an alternative source of protein to conventional meat. Furthermore, their edible portion is at 80%, which is significantly higher than that of beef (40%) [6]. Insect-based foods have a better greenhouse gas balance than beef and pork, although the exact environmental impact depends on the insect species [5]. However, despite the advantages mentioned above, eating insect-based foods has not yet become commonplace in Germany.

In addition to the two types of products mentioned above, another meat alternative with great potential could be available in supermarkets in the future: cultivated meat. Experts predict that in only 15 years, cultivated meat could take over a third of the conventional meat market share. Compared to plant-based meat substitutes, cultivated meat is said to have the same nutritional value, texture, and taste as meat, making it a biological equivalent. Cultivated meat is produced via cell and tissue culture techniques. The basis is usually animal muscle cells, which are placed in a bioreactor with a nutrient medium, where they first multiply and then develop into tissue. The production of 1 kg of cultivated beef is expected to require fewer resources than the production of the same amount of conventional beef (e.g., around 94% less land usage) while providing equivalent nutritional value. Several companies are working on the development of cultivated meat and fish already [7].

Drivers of and barriers to the consumption of meat alternatives

Despite advances in the development and optimization of meat alternatives, the consumption of meat and meat products in Germany in 2023 was still around 53 kg per person [8]. Simultaneously, interest in plant-based and novel meat alternatives is steadily increasing.

Plant-based meat alternatives

In 2023, 16.6% more plant-based meat alternatives were produced than in the previous year [9]. The consumption of plant-based alternatives has also increased in recent years, which can be attributed to both personal and product-related factors. Personal food choice motives, such as the naturalness of products, animal welfare, and the environment, have a positive influence on the consumption of plant-based alternatives [10], [11]. In addition, familiarity with plant-based meat substitutes promotes their consumption, while the social environment also plays a key role: If an individual’s partner has a positive attitude toward meat alternatives, the likelihood that the individual will also develop a positive attitude is greater, resulting in increased consumption [10].

Perceptions of plant-based meat alternatives can also have a negative impact on consumption. Many people consider these alternatives to be less tasty, artificial, unnecessary, boring, or more expensive than conventional meat. In addition, some meat alternatives have unfamiliar textures or flavors that are perceived to be unpleasant [10], [11]. In addition to this disgust, a general fear of novel foods (or food neophobia) also reduces people’s willingness to consume plant-based meat alternatives (Table 1) [10].

Insects

Overall, 13% of the population in Germany could imagine eating insects [12], while 41.9% would be willing to consume an insect-based burger [13]. Knowledge about the environmental benefits and nutritional content of insects plays a key role in their consumption [13].

However, insect-based foods have not yet become widely accepted in Germany. The main barrier to their consumption is the

perception of insects as unhealthy, unappetizing, and dirty. Like plant-based alternatives, they can arouse fear and disgust among consumers. In Germany specifically, and in Western societies in general, the inhibition threshold for consumption is thus rather high [13]. The limited availability of insect-based foods in German supermarkets is also a barrier to their consumption. Without regular access, the possibility of normalizing and accepting insect-based foods remains limited (Table 1) [5].

Cultivated meat

Fourteen percent of the German population would be willing to consume cultivated meat [12], while 58.4% would be willing to consume a burger made with cultivated meat [7]. Cultivated meat is considered to have great market potential because it offers consumers a way to consume “meat” without causing animal suffering [14]. It is a particularly suitable alternative for people who do not want to give up meat because of its taste (Table 1) [14].

However, the perception of cultivated meat as potentially expensive and unnatural may reduce people’s willingness to consume it [14]. Many people are also uncertain about its possible long-term effects on their health [15]. Food neophobia is a barrier, too (Table 1) [16].

Notably, cultivated meat will only be approved as a novel food in Europe if, after extensive testing, it is found to have no safety risk to human health [17].

Table 1: A comparison of meat alternatives - drivers and barriers of consumption

| Meat alternatives | Drivers of consumption | Barriers to consumption |

| Plant-based alternatives | Reduction of meat consumptiona Personal healtha Animal welfarea Environmental protection (climate protection)a; d Familiarity Attitudes in the social environment |

Perception of alternative as more expensive, artificial, unnecessary, boring, and less tastya Unfamiliar tastea Unfamiliar consistencya Fear of novel foods (or food neophobia)c |

| Insect-based alternativey | Curiositye Nutrient content (protein content)b Environmental impactb |

Perception of insects as harmful to health and dirtye Anticipated tastee Fear and disguste Low availability and selection in supermarketsf |

| Cultivated meat | Expected taste and consistencyg Nutrient content (equivalent to meat)c Animal welfareg |

Perception of cultivated meat as more expensive and unnaturalg (manufacturing process) Fear of novel foods (or food neophobia)i Uncertainty and security concernsh |

Note: The above table is incomplete; it is merely meant to provide an illustrative overview of relevant drivers and barriers. a [10], [11]; b[18]; c[7]; d[4]; e[13]; f[5], g[14]; h[15]; i[16]

Everything new, or everything the same—How do I decide?

As described above, from a consumer perspective, each meat alternative has advantages and disadvantages. Each person must decide for themselves which alternatives (if any) they want to include in their diet. This choice, however, is influenced by various factors, and the drivers and barriers presented above have a different weighting and thus a different influence for each person. The decisive factor is which product suits the individual’s motives best – for example, culinary enjoyment versus environmental protection (Figure 2). At the same time, the influence of an individual’s social environment should not be underestimated. Diet and consumption often depend more on an individual’s social context and less on individual decisions. Family, friends, and colleagues have a major influence on the products we buy and eat. Accordingly, factors such as social norms should not be ignored.

A meat alternative should taste similar to meat, be environmentally and animal-friendly, and be affordable. On the other hand, it is important to address uncertainties, fears, and disgust surrounding such alternatives. Plant-based, insect-based, and cultivated meat alternatives differ in these characteristics but are more sustainable than conventional meat in many respects. It is likely that this diversity of alternatives is necessary to ensure that there is an option available for all consumers.

Figure 2: Which alternative burger patty should I choose?

Figure 2: Which alternative burger patty should I choose?

Bibliography

[1] C. J. Hopwood, W. Bleidorn, T. Schwaba, and S. Chen, “Health, environmental, and animal rights motives for vegetarian eating,” PloS ONE, vol. 15, no. 4, art. no. e0230609, Apr. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230609.

[2] B. Bastian, and S. Loughnan, “Resolving the meat-paradox: A motivational account of morally troublesome behavior and its maintenance,” Personality and Social Psychology Review, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 278–299, May 2017, https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868316647562.

[3] B. Buttlar and E. Walther, “Das Fleischparadox: Warum es so schwerfällt, auf Fleisch zu verzichten [The meat paradox: Why it’s so difficult to give up meat],” The Inquisitive Mind, vol. 2, 2020.

[4] T. Jetzke, S. Richter, B. Keppner, L. Domröse, S. Wunder, and A. Ferrari. “Die Zukunft im Blick: Fleisch der Zukunft [Looking to the future: Meat of the future].” Umweltbundesamt.de. Accessed: Oct. 14, 2024. [Online.] Available: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/publikationen/die-zukunft-im-blick-fleisc...

[5] Press and Information Office of the Federal Government. “Insekten als Lebensmittel [Insects as food]”. Bundesregierung.de. Accessed: Aug. 20, 2024. [Online.] Available: https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/themen/nachhaltigkeitspolitik/ins...

[6] F. Fiebelkorn, “Insekten als Nahrungsmittel der Zukunft [Insects as food for the future]”, Biologie in Unserer Zeit, vol. 47, no. 2, pp. 104–110, 2017.

[7] F. Fiebelkorn, J. Dupont, L. Szczepanski, and N. Filko, “Fleisch (r) evolution: Produktion, Nachhaltigkeit und Akzeptanz von kultiviertem Fleisch [Meat (r) evolution: Production, sustainability, and acceptance of cultivated meat],” Biologie in unserer Zeit, vol. 52 no. 3, pp. 248–261, 2022, https://doi.org/10.11576/biuz-5695.

[8] Federal Office for Agriculture and Food. “Versorgungsbilanz Fleisch: Verzehr leicht gestiegen [Meat supply balance: consumption slightly up].” Ble.de. Accessed: May 9, 2025. [Online.] Available: https://www.ble.de/SharedDocs/Pressemitteilungen/DE/2025/250327_Fleischb...

[9] Federal Statistical Office of Germany. “Trend zu Fleischalternativen ungebrochen: Produktion steigt 2023 um 16,6 % gegenüber dem Vorjahr [Trend toward meat alternatives continues unabated: Production to rise by 16.6% in 2023 compared to the previous year].” Destatis.de. Accessed: Apr. 4, 2025. [Online.] Available: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Presse/Pressemitteilungen/2024/05/PD24_N018_4...

[10] A. C. Hoek, P. A. Luning, P. Weijzen, W. Engels, F. J. Kok, and C. de Graaf, “Replacement of meat by meat substitutes. A survey on person-and product-related

factors in consumer acceptance,” Appetite, vol. 56, no. 3, pp. 662–673, Feb. 2011, doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.02.001.

[11] F. Michel, C. Hartmann, and M. Siegrist, “Consumers’ associations, perceptions and acceptance of meat and plant-based meat alternatives,” Food Quality and Preference, vol. 87, Jan. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2020.104063.

[12] Statista, “Können Sie sich vorstellen, Laborfleisch zu essen?[Can you imagine eating lab-grown meat?].” Accessed: Oct. 14, 2024. [Online.] Available: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/1244081/umfrage/umfrage-z...

[13] T. Kröger, J. Dupont, L. Büsing, and F. Fiebelkorn, “Acceptance of Insect-Based Food Products in Western Societies: A Systematic Review,” Frontiers in Nutrition, vol. 8, art. no. 759885, Feb. 2022, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.759885.

[14] C. Bryant, and J. Barnett, “Consumer acceptance of cultivated meat: An updated review (2018–2020),” Applied Sciences, vol, 10, no. 15, art. no. 5201, July 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/app10155201.

[15] E. Shaw, and M. Mac Con Iomaire, “A comparative analysis of the attitudes of rural and urban consumers towards cultivated meat,” British Food Journal, vol. 121, no. 8, pp. 1782–1800, June 2019, https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-07-2018-0433.

[16] O. Meixner and L. M. von Pfalzen, Die Akzeptanz von Insekten in der Ernährung [The acceptance of insects in the diet]. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler, 2018.

[17] Federal Office for Agriculture and Food. “Spezielle Lebensmittel – Neuartige Lebensmittel –

Novel Food [Special foods – novel foods –

novel food].” Bmel.de. Accessed: Aug. 10, 2024. [Online.] Available: https://www.bmel.de/DE/themen/verbraucherschutz/lebensmittelsicherheit/s...

[18] S. Mancini, G. Sogari, D. Menozzi, R. Nuvoloni, B. Torracca, R. Moruzzo, and G. Paci, “Factors Predicting the Intention of Eating an Insect-Based Product,” Foods, vol. 8, no. 7, art. no. 270, July 2019, https://doi.org/10.3390/foods8070270.

Figures

Illustration by authors