Players behind the scenes: How parents join their children’s road to the Olympics

Editor: Elisa Bisagno

Editorial Assistant: Sameeksha Shukla, Jana Dreston

This article has also been translated into German and French.

At the end of their Olympic careers, many athletes acknowledge the contributions of a hidden participant: their parents. In the present article, the authors review the pivotal impact of parents’ support for children’s development and success in elite sports and share insights on what constitutes positive parental involvement.

Did you know that being related to an Olympic medalist increases your probability of winning a medal by about 20 percent [1]? A closer look at Olympic start lists reveals a multitude of athletes with Olympic family ties such as skiers Hubert and Johannes Strolz (Austria), swimmers Gary Hall Sr. and Jr. (USA), Philippe and Marcel Rozier (equestrian jumping, France), the Keller family (

field hockey, Germany), the Karabatic family (handball, France), or gymnast Jade Carey (USA), who is coached by her father. At the end of their careers, many Olympic athletes acknowledge the immense contributions of their parents. Basketballer Dirk Nowitziki even thanked his parents for their unconditional support and the sacrifices they made to facilitate his athletic career at his recent Hall of Fame Induction [2]. Although visible on the sidelines and in the bleachers, parents often are the “hidden participants”, acting in the background and being overlooked in youth sport and elite performance pathways [3]. To learn more about parental involvement, sport psychology researchers have increasingly focused on how parents support youth athletes’ elite performance and what impact parents’ involvement has on athletes and themselves.

Whether in school, arts, or sports, having supportive parents is an essential factor for children’s and youth’s talent development [4]. In modern day elite sport, parents provide the opportunity for participation, engage in behaviors to nurture talent, and offer forms of instrumental, informational, and emotional support [5]. For example, they introduce youth athletes to a sport, travel to practices and competitions, purchase equipment and uniforms, share career advice, and provide comfort after poor performances or a defeat. All told, parents dedicate

significant time, money, and emotional energy into nurturing the next generation of Olympic athletes. In this way, parents can be viewed as the earliest and perhaps most powerful influencers that shape youth athletes’ experiences in elite sport. With increasing age and maturity, peers and coaches often become more salient

significant others, as adolescents rely more heavily on their views to manage challenges in sport and life.

Image 2: Types of parental support in elite sport

Image 2: Types of parental support in elite sport

Changing phases, changing support

Considering that the youngest athlete at the Tokyo 2020 Olympics, Japanese skateboarder Nishiya Momiji, was just 13 years old, the support and guidance of parents in elite sports seems ever present. The support athletes need from their parents changes as they progress in age, skill, and development [6]. In general, parents are understood as a psychosocial resource which guide and facilitate youth athletes’ elite sport careers. Among their support, parents should provide athletes with opportunities to engage in physical activity which are developmentally appropriate (i.e., age, level of maturity) and related to individual goals 6 (i.e., recreational participation or elite performance; [6]). In sport psychology, the developmental model of sport participation [7] summarizes pathways youth athletes can pursue in sport depending on whether they prefer an engagement in recreational physical activity or aim to become an elite athlete. The model distinguishes three distinct phases of sport participation: sampling, investment, and specialization.

The sampling stage (ages 6 to 13) is characterized by a high amount of sport activities which athletes pursue for their own sake and which are enjoyable and rather unstructured, such as backyard soccer. As such, youth athletes tend to participate in multiple sports, and parents typically provide opportunities for free play, enjoyment, and skill learning along with the tangible resources necessary to participate. During this stage, parents can maximize athletes’ development by being emotionally available and discussing their experiences regularly. For example, Italian tennis player Jannik Sinner shared after this 2024 Australian Open win that when growing up, his parents let him try different sports including skiing, soccer, and tennis. He further recognized: “They never put pressure on me, and I wish this freedom is possible for as many young kids as possible” [8].

Progressing into the specialization stage (ages 13 to 15), youth athletes’ engagement in free play and deliberate training becomes balanced. During this stage, they tend to participate in fewer sports but progress to a more elite level of participation and competition. To foster youngsters’ engagement during this stage, parents often invest an increasing amount of time, financial, and emotional resources into youth athletes’ participation and competition. As the American gymnast and Olympic medalist Simone Biles shared about her parents’ involvement: “They have sacrificed so much for me to do what I love. (…) They have always been there supporting me, so I cannot thank them enough” [9]. Further, it becomes particularly important for parents to support youth athletes’

autonomy development by allowing them to make their own sport-related decisions and to manage interactions with coaches and peers independently.

For athletes who have the opportunity to continue participating into late adolescence, the transition to focusing on elite skill development in a single sport occurs during the investment stage (age 15 and above). Investing in a sport is characterized by a high amount of training targeted at performance improvement and less free play. During this stage, the athlete’s competitive endeavors should be athlete- and not parent-driven; parents should act in the background and should adapt their support to the individual preferences of their aspiring athlete. For example, tennis legend Roger Federer recalled: “I had to sort of take a decision, soccer or tennis. It was quite easy to be honest, I was successful in soccer, but it doesn’t go at the pace as tennis goes. Soccer takes many more years. (…) Then of course I chose tennis (…)” [10]. According to sport psychology research, elite sport performance of Olympic athletes can either be achieved through progressing from an initial sampling to a late specialization stage as in the example of Roger Federer [e.g. 11] or through an early specialization [e.g. 12]. The latter, however, might come at the cost of overuse injuries and decreased mental health [13, 14]. Image 3: Parenting athletes across career stages

Image 3: Parenting athletes across career stages

Athletes have individual preferences for parental support

Researchers have long debated what contributes to parental support in (elite) youth sport being positive. Scientifically speaking, it is a bit more complicated than labeling parents’ behaviors as “good” or bad”. It also seems oversimplified to only consider the behaviors that parents display in the absence of the interpersonal and environmental contexts that surround them. What remains most important is how youth athletes perceive and interpret their parents’ behavior and when the parents provide it [15]. For example, boys who are involved in elite sport settings attribute the highest importance to their fathers’ behaviors [16]. Female elite athletes express preferences for their parents’ behavior depending on the time point: supporting physical and mental preparation is most important before the competition; showing encouragement and focusing on effort compared to outcome is most important during the competition; and providing positive and realistic feedback is most important after the competition [17].

These preferences for parental support are further influenced by the individual characteristics of athletes and their parents, as well as the context in which support is provided [18]. When in a negative mood or after a bad performance, youth athletes’ support preferences varied from wanting to feel connected to someone, needing a listening ear, requesting feedback, or simply wanting to be alone. Further, athletes appreciated informational support by their parents only if they perceived that their parents had sufficient sport-specific knowledge and ability, for example, by having been a former elite athlete themselves. In cases where parents adopt a dual role in parenting and coaching their children, the provision of individual support can even be decreased to maintain the appearance of a fair coach treating all athletes equally [19].

What does providing support mean for parents?

In 2010, Ana María Parera, mother of Rafael Nadal shared:

“… when I'm watching a match, I see from a distance whether or not he has problems, and when he does, I want the match to end. I can’t watch him suffer, it’s too much for me. (…) When he wins a big one it’s impressive because at home I see how much he works, how much he struggles. From the outside you only see the spectacle and, make no mistake, this world is very hard, it’s full of obstacles” [20].

Supporting elite athletes can be a challenge. Parents of youth athletes have to deal with several stressors to support their child and guide them to the highest performance level [21]:

- Organizational stressors involve personal investments (e.g., time and finance), demands related to athlete’s health (e.g., doping, injuries, and health integrity in the medium and long term), logistics (e.g., sponsors, adapting family planning, and laundry), and sport systems (e.g., communication and quality of training and coach).

- Developmental stressors refer to demands concerning youth athletes’ future ( commitment to studies or a professional project different from the sports project) and their holistic development (e.g., disinterest in friends outside the sporting context and other extra-sport activities).

- Competitive stressors include demands associated with an athlete’s psychological readiness, physical ability, attitude or behavior, the preparation for competition, attending competitions as well as the behavior of opponents or other parents.

- Personal stressors involve demands related to parents’ physical distance from their aspiring athlete (i.e., elite sport very often involves moving away from home), their provision of support, and their interaction with other agents in the youth sport environment (e.g., jealousy of other athletes’ parents).

In cases where parents have difficulties to manage their sport-related stress and negative emotions, consequences can affect both athletes and parents, for example through expressing punitive behaviors, derogatory comments, or conditional love [22]. In these instances, even well-intentioned support such as debriefing, feedback, or an excessive involvement through cheering can unintentionally upset youth athletes and disrupt their performance [e.g. 23]. In contrast, parents also enjoy positive experiences through their child’s sport involvement [22]: the time spent together on the road traveling to competitions and consistently sharing the emotional highs and lows associated with sport can strengthen parent-child relationships, especially closeness. Parents’ regular involvement in elite sport also enables them to extend peer networks, as some parents meet new friends in their children’s sporting environment. Finally, parents not only experience stress and negative sport-related emotions but a variety of pleasant emotions as well. Specifically, feelings of pride, excitement, enjoyment, and satisfaction are associated with observing children compete and engaging with other social agents (i.e., teammates and coaches).

Strategies to facilitate parental support

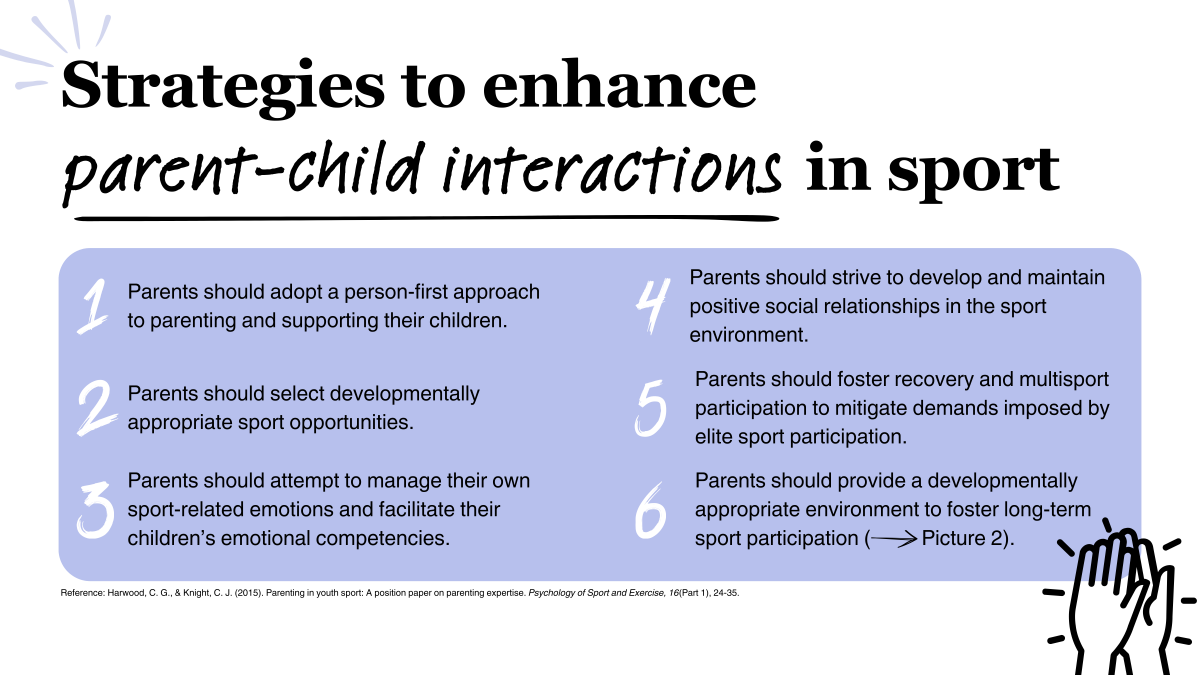

According to a recent review [24], parent-education programs can have positive effects on parents (e.g., sport-specific competence and knowledge, support, verbal behavior), youth athletes (e.g., enhanced enjoyment and motivation), as well as the parent-child relationship. Specifically, to ensure parental involvement promotes youth athletes’ development and flourishing, [25] proposed six strategies that teams and organizations should address during parent education to enhance parental support. First, parents should help youth athletes to select appropriate sporting opportunities, taking into account their developmental progress and competitive goals. Second, parents should strive to understand and apply appropriate parenting styles in sport, based on the unique relationships they have with their children. Third, parents should attempt to manage the emotional demands of sport, protecting youth athletes from the stresses of high-stakes competition. Fourth, parents should strive to foster healthy relationships with their children, other parents, and their children’s coaches. Fifth, parents should manage the demands associated with youth sport by allowing for downtime and multisport participation. Finally, parents should adapt their children's environments across the stages of sport participation with an eye toward long-term athlete development. In utilizing these strategies, parents should attempt to meet the introductory, organizational, developmental, and competitive needs of their aspiring athletes over the course of (elite) sport participation [26].

Image 4: Strategies to enhance parent-child interactions in sport

Image 4: Strategies to enhance parent-child interactions in sport

Although it is easy to prescribe solutions for negative parent behavior (e.g., “Silent Saturdays”, parent contracts,

social media campaigns encouraging positive behavior), evidence-based parent education programs have yet to be systematically implemented and assessed across a wide range of youth sport settings and cultures. No two athletes, families, or sport contexts are the same, and it is incumbent upon researchers and practitioners to avoid treating parent education as a one?size-fits-all proposition.

Parental support as a performance catalyst?

Good news: Most parents seem to have a positive impact on their athletic children and perceptions of negative parenting in sports range from 14% to 36% [27, 28]. Parents who value learning and enjoyment, who express satisfaction with their children’s sport performances, and who share encouraging comments, allow youth athletes to benefit from a range of positive effects through their sport participation [29]. In contrast, when parents overemphasize winning, make love and attention contingent upon excellent performance, or pressure their children to perform, they contribute to harmful consequences and youth athletes quitting their sports participation prematurely [30]. Surprisingly, no study to date has examined the direct influence of perceived parental support on athletic success. Instead, the collective body of knowledge suggests that positive parental support facilitates an elite sport career by impacting key components of continued sport participation: enjoyment, autonomous motivation to participate, and perceived sport-related

competence.

To conclude, the ways youth athletes perceive their parents’ involvement across their sports careers have the potential to determine whether they continue or discontinue participation. Given that drop-out rates have been increasing in recent years, particularly among adolescents and females, it is worth taking a closer look at the complexities of parental behavior. While being related to an Olympic medalist increases your probability of winning a medal, there are many ways in which parents can contribute to the success of aspiring athletes, despite often acting in the background. An ongoing and individually tailored education of parents on how they can facilitate the involvement of their children in sports should therefore be prioritized in the development of the next generation of Olympic athletes.

Bibliography

[1] Antero, J., Saulière, G., Marck, A., & Toussaint, J. F. (2018). A Medal in the Olympics Runs in the Family: A Cohort Study of Performance Heritability in the Games History. Frontiers in physiology, 9, 1313. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.01313

[2] Eschenbach, J. (2023). "For the rest of my life, I will never forget what you have done for me" - Dirk Nowitzki pays tribute to parents in emotional Hall of Fame speech. Basketball Network. Retrieved 13 February 2024 from https://www.basketballnetwork.net/off-the-court/dirk-nowitzki-pays-tribu...

[3] Dorsch, T. E. (2017). Optimising family involvement in youth sport. In C. Knight, C. Harwood, & D. Gould (Eds.), Sport psychology for young athletes (pp. 106-115). Routledge.

[4] Kiewra, K. A. (2019). Nurturing children’s talents: a guide for parents. Praeger.

[5] Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2004). Parental influences on youth involvement in sports. In Developmental sport and exercise psychology: A lifespan perspective. (pp. 145-164). Fitness Information Technology.

[6] Côté, J. (1999). The influence of the family in the development of talent in sport. The Sport Psychologist, 13(4), 395-417. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.13.4.395

[7] Côté, J., Baker, J., & Abernethy, B. (2007). Practice and play in the development of sport expertise. In G. Tenenbaum & R. C. Eklund (Eds.), Handbook of Sport Psychology (3rd ed., pp. 184-202). Wiley.https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118270011.ch8

[8] Pentony, L. (2024). Jannik Sinner credits parents with Australian open win over Daniil Medvedev. ABC News. Retrieved 23 April 2024 from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-01-29/australian-open-jannik-sinner-pra...

[9] Roberts, Z. (2024). „I cannot thank them enough” – Simone Biles describes her parents’ support during her first-ever Olympics selection in 2016. Sportskeeda. Retrieved 23 April 2024 from https://www.sportskeeda.com/us/olympics/i-thank-enough-simone-biles-desc...

[10] Gatto, L. (2019). Roger Federer explains why he chose tennis over football. Tennis World USA. Retrieved 23 April 2024 from https://www.tennisworldusa.org/tennis/news/Roger_Federer/68180/roger-fed...

[11] Bridge, M. W., & Toms, M. R. (2013). The specialising or sampling debate: A restrospective analysis of adolescent sports participation in the UK. Journal of Sports Sciences, 31(1), 87-96. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2012.721560

[12] Young, B. W., Eccles, D. W., Williams, A. M., & Baker, J. (2021). K. Anders Ericsson, deliberate practice, and sport: Contributions, collaborations, and controversies. Journal of Expertise, 4(2), 169-189.

[13] Myer, G. D., Jayanthi, N., Difiori, J. P., Faigenbaum, A. D., Kiefer, A. W., Logerstedt, D., & Micheli, L. J. (2015). Sport specialization, Part I: Does early sports specialization increase negative outcomes and reduce the opportunity for success in young athletes? Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach, 7(5), 437-442. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941738115598747

[14] Strachan, L., Côté, J., & Deakin, J. (2009). “Specializers” vs. “samplers” in youth sport: Comparing experiences and outcomes. The Sport Psychologist, 23(1), 77–92.

[15] Holt, N. L., & Knight, C. (2014). Parenting in youth sport: From research to practice. Routledge.

[16] Lewko, J. H., & Ewing, M. E. (1980). Sex differences and parental influence in sport involvement of children. Journal of Sport Psychology, 2(1), 62–68.

[17] Knight, C. J., Neely, K. C., & Holt, N. L. (2011). Parental behaviors in team sports: How do female athletes want parents to behave? Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 23(1), 76–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2010.525589

[18] Burke, S., Sharp, L.-A., Woods, D., & Paradis, K. F. (2023). Advancing a grounded theory of parental support in competitive girls’ golf. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 66: 102400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2023.102400

[19] Elliott, S., & Drummond, M. (2017). The experience of parent-coaches in youth sport: A qualitative case study from Australia. Journal of Amateur Sport, 3(3), 64-85. https://doi.org/10.17161/jas.v3i3.6511

[20] Rafaholics (2010). Rafa Nadal's mother Ana Maria Parera interview. Rafaholics. Retrieved 13 February 2024 from http://www.rafaholics.net/2010/12/rafa-nadals-mother-ana-maria-parera.html

[21] Lienhart, N., Nicaise, V., Knight, C. J., & Guillet-Descas, E. (2020). Understanding parent stressors and coping experiences in elite sports contexts. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 9, 390-404. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/spy0000186

[22] Sutcliffe, J. T., Fernandez, D. K., Kelly, P. J., & Vella, S. A. (2021). The parental experience in youth sport: a systematic review and qualitative meta-study. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1-28. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2021.1998576

[23] Elliott, S., & Drummond, M. (2015). Parents in youth sport: What happens after the game? Sport, Education and Society, 22(3), 1-16. https://doi.org./ 10.1080/13573322.2015.1036233

[24] Burke, S., Sharp, L.-A., Woods, D., & Paradis, K. F. (2021). Enhancing parental support through parent-education programs in youth sport: A systematic review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology. Advance online publication: https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2021.1992793

[25] Harwood, C. G., & Knight, C. J. (2015). Parenting in youth sport: A position paper on parenting expertise. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 16(Part 1), 24–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.03.001

[26] Thrower, S. N., Harwood, C. G., & Spray, C. M. (2016). Educating and supporting tennis parents: A grounded theory of parents’ needs during childhood and early adolescence. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 5(2), 107–124. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000054

[27] Gould, D., Lauer, L., Rolo, C., Jannes, C., & Pennisi, N. (2006). Understanding the role parents play in tennis success: A national survey of junior tennis coaches. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 40(7), 632–636. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2005.024927

[28] Shields, D. L., Bredemeier, B. L., LaVoi, N. M., & Power, F. C. (2005). The sport behavior of youth, parents, and coaches: The good, the bad and the ugly. Journal of Research in Character Education, 3(1), 43-59.

[29] Blom, L. C., Visek, A. J., & Harris, B. S. (2013). Triangulation in youth sport: Healthy partnerships among parents, coaches, and practitioners. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 4(2), 86–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2012.763078

[30] Gould, D., Feltz, D., Horn, T., & Weiss, M. R. (1982). Reasons for attrition in competitive youth swimming. Journal of Sport Behavior, 5(3), 155–165.

Images

Image 1. Pixabay: https://pixabay.com/photos/family-holding-hands-parents-child-1866868/

Image 2. Self-created, property of the authors

Image 3. Self-created, property of the authors

Image 4. Self-created, property of the authors