Sleep before, during and after the Olympic Games: an important determinant of sports performance

Editor: Sylvain Laborde

Editorial Assistant: Jana Dreston

This article has also been translated into German, French, and Italian.

This article focuses on the basics of normal sleep and the various sleep problems in competitive sports athletes. Strategies and tips for improving sleep behaviour of athletes before, during, and after major competitions such as the Olympic Games are be provided.

The fact that sleep is essential for physiological and

psychological well-being is well known to all athletes today. At the 2008 Olympics in Beijing, Usain Bolt won the 100m and the 200m, while breaking both world records, thereby earning the title of fastest man in the world. After the Olympics, Bolt said the most important part of his intense training regimen was sleep: “Sleep is extremely important to me – I need to rest and recover in order for the training I do to be absorbed by my body”. Every sport requires both muscular and cognitive recovery, and only a well-rested athlete is capable of peak performance. The National Sleep Foundation for Healthy Sleep recommends 7-9 hours of sleep for a healthy adult [1]. Restful sleep (>85% sleep efficiency, <30 min sleep latency, <40 min wake time after sleep onset) is therefore essential for competition preparation and recovery.

Many

factors can adversely affect an athlete’s sleep: changes in temperature and/or altitude, traveling across time zones, stress and

anxiety related to competition, as well as changes in diet and training times or duration, constant changes in the external and sleep environment, and variations in the day/night rhythm characterize the season of a professional athlete. However, the results of sleep research have only played a minor role in competitive sports. Therefore, this review will provide relevant knowledge about sleep physiology and basic critical points about normal sleep and various sleep disorders. The effects of sleep during training and competition, for example during the Olympic Games, will be discussed. This review aims to demonstrate the importance of restorative sleep, particularly for athletes, in

relation to health, recovery and performance. Based on this, guidelines and instructions for strategies and tips to improve the sleep behavior of athletes will be provided.

Why do we sleep and how much sleep do we need?

On average, we spend a third of our lives asleep. By the time we reach the age of 85, we will have spent approximately 30 years asleep. Sleep is known to be highly inter- and intra-individually variable. Numerous studies have shown that individual sleep duration varies widely, particularly among athletes [2]. Recent studies have found that, on average, athletes sleep significantly less (6-8 hours) than the recommended 7-9 hours [3] and that they get approximately 96 minutes less sleep than they need to feel refreshed [4]. In general, findings of suboptimal sleep variables in athlete populations have been reported. Recently, for example, [5] studied the sleep of Olympic-level track and

field athletes prior to the Tokyo 2021 Olympic Games and found that 18.8% of athletes were poor sleepers, with sleep efficiency < 85%, and 31.3% were short sleepers, with total sleep time <7 hours.

It is recommended that you adjust your sleep to your individual optimal sleep duration and circadian phase. Although the function of sleep is not yet known, several processes may be sleep-dependent. One function may be related to recovery of the body and central nervous system. An increase in growth hormone levels during the first half of the night and replenishment of glycogen stores may support this idea. Both metabolism and body temperature decrease during sleep, which also suggests an energy-saving function. For athletes in particular, the importance of sleep for a functioning immune system should be emphasized. Sleep deprivation studies in animals and humans show an increased susceptibility to infection with reduced sleep duration. Furthermore, the

consolidation of

memory and newly learned knowledge during sleep has been scientifically proven [6]. Tasks learned before a period of sleep are more likely to be retained than tasks learned before a period of wakefulness. These findings are also consistent with the common complaints of

memory and concentration problems among athletes with impaired sleep quality. Researchers [2] found that there is no direct effect of reduced sleep quality on athletic performance but rather an indirect effect through emotional instability, lack of motivation and concentration, and impaired cognitive performance.

Sleep and sleep disorders in elite sport

Although regular physical activity and exercise improve sleep, poor sleep is common among elite athletes [7]. In general, athletes seem to have a similar prevalence of sleep disorders (e.g., sleep-related breathing disorders) as the general population. This means that organic sleep disorders are just as common in professional athletes as in the general population, but are usually overlooked. However, professional sport also offers several specific situations that interfere with normal sleep: both excessive training volume [8] and high training intensity immediately before bedtime (40 minutes of treadmill training at 80% of HRmax at 9:30 p.m.; [9] can have a negative impact on sleep quality. For example, higher excercise intensity may lead to longer wake times during the night. Depending on the severity of the sleep disorder that may have developed, athletes sometimes report isgnificant impairment and feel unable to perform optimally in competition.

Athletes often report problems with falling asleep, waking up early in the morning, and waking up the night before competition. For example, higher levels of psychological stress among athletes during the Rio 2016 Olympic Games led to increased sleep disturbances and increased daytime dysfunction [10]. Awareness of poor sleep quality prior to competition may lead to daytime dysfunction such as nervous overreaction, poor decision making, or early withdrawal during competition. In addition, sleeping in an unfamiliar environment and/or adjusting to a different time zone often impairs subsequent sleep. Cross-sectional data suggest that athletes and support staff have little or no knowledge of strategies for managing sleep problems before, during, and after competition. The following section reviews sleep disturbances associated with time zone changes.

Jetlag and travel stress

Jetlag is a temporary sleep disorder that occurs when the internal circadian rhythm is misaligned due to transmeridian travel. The disorder is characterized by varying degrees of difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep, excessive daytime sleepiness, reduced daytime alertness and performance, and vegetative symptoms (e.g., changes in appetite, increased frequency of waking to urinate during the night). In addition to the disruption of the sleep-wake cycle, other bodily functions (e.g., body temperature, digestion) that are subject to circadian rhythms may also be affected. It can also cause headaches and dizziness.

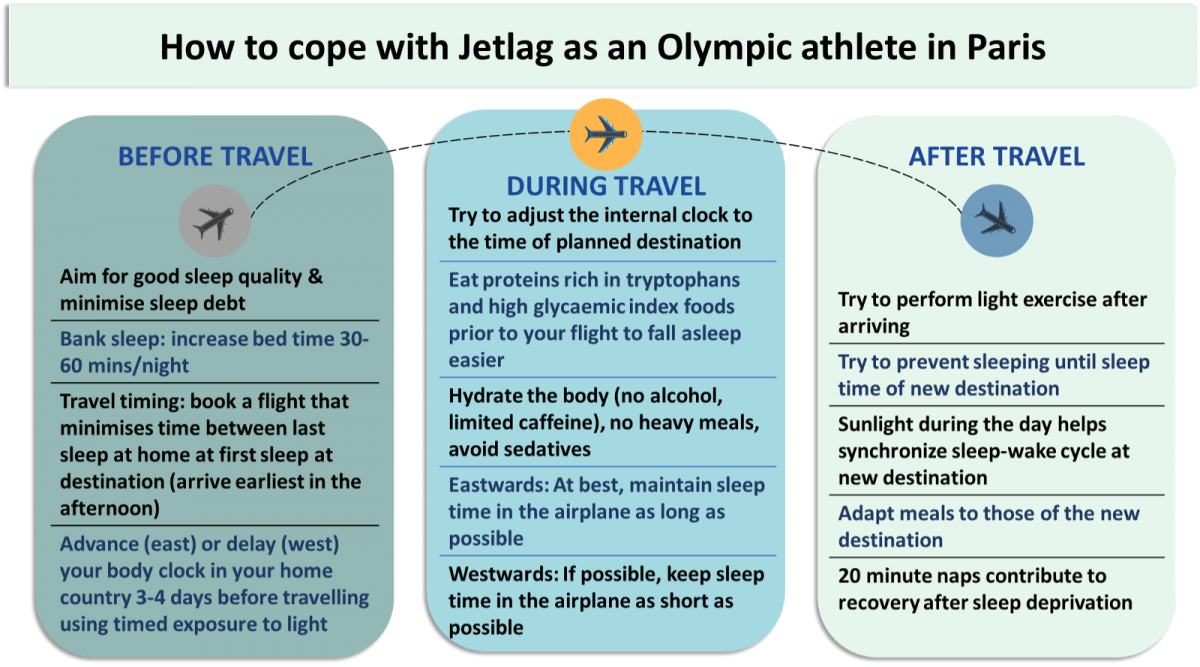

ATP world number one Iga Swiatek shares her secret for dealing with jetlag: sometimes when she travels from Australia to the Middle East and then to the United States, it's all right for her, but when she comes back to Europe, or when she goes from the United States to China, it's very difficult. "Going from west to east, I just need a little help like melatonin.” Her sports psychologist also helps by providing her with different lamps with good brightness. These lamps help Iga maintain a 24-hour cycle and a good sleep rhythm. She also describes how sticking to a training routine helps her get back into a good sleep-wake cycle: "When I'm practicing, it's a lot easier to somehow get through it. Sometimes, like after the US Open, I had a week off and it was much harder to get back into the rhythm." (Iga Swiatek; https://www.tennis.com/baseline/articles/iga-swiatek-shares-her-secret-f...). Many of the athletes competing at the Paris Olympic Games will experience jetlag symptoms and are advised to follow some guidelines to manage jetlag symptoms and fatigue ([11]; see Figure 1).

Flight direction plays an important role in the development of jetlag symptoms. In general, westbound flights, which lengthen the day, are better tolerated by the body than eastbound flights, which shorten the day. This is because our internal clock does not run exactly 24 hours a day, but in slightly longer phases. Flights to the west are therefore more accommodating to the internal clock. For example, if you fly from Paris, France to San Francisco, USA and land there at 6 p.m., it will be midnight in France. If you stay awake for a few more hours, you will go to bed very tired and exhausted, but you will adapt well to the new sleep-wake rhythm. On the other hand, if you fly from San Francisco to Paris and arrive at 6 p.m., your body is still used to the time in San Francisco (it is only 12 p.m. here). That's why it's usually harder to fall asleep in just a few hours. The more time zones you cross, the more severe the symptoms. In general, you can expect to take about a day to adjust to each time zone, depending on your health, age, travel experience, and

chronotype.

Athletes, in particular, who change time zones frequently are advised to adjust to the time in the destination country as early as possible. With 6-hour time difference, it is best to arrive at least 6 days before the competition. If this is not possible, you can take certain precautions in your home country. For eastbound flights, you should set your body clock forward 3-4 days before traveling (e.g., go to bed an hour earlier and get up an hour earlier). The opposite is true for westbound flights. An early adjustment using timed light exposure (e.g., light stimulation with a daylight lamp) to suppress melatonin secretion while facilitating wakefulness may help. Light should be sought in the early evening hours and avoided in the second half of the night and early morning. Sunglasses can be used to reduce light. It is recommended that you book a flight that arrives in the afternoon so that you can go to sleep in the foreseeable future. It is recommended that you set your watch to the time in your destination country and that you behave according to the time in the destination country during the flight. For example, most airlines now serve meals in line with these recommendations. Stay hydrated during the flight but avoid caffeine. Once you arrive at your destination, a short nap (20 minutes or less) can help you recover from sleep deprivation. Natural light is always preferable to artificial light and helps to alter the sleep-wake cycle.

See Image 3 for specific strategies to manage jetlag before, during, and after the flight. Please note that there are numerous strategies to mitigate jetlag and travel stress, depending on your departure location and resources. While it is difficult to summarize all these tactics in a single figure, we have highlighted a few key strategies. However, these may change depending on

factors such as the length of the trip, departure time, etc. Nevertheless, it is always a good idea to consult a professional sleep coach before travelling!

Image 3. Strategies for jetlag management before, during and after travel.

Image 3. Strategies for jetlag management before, during and after travel.

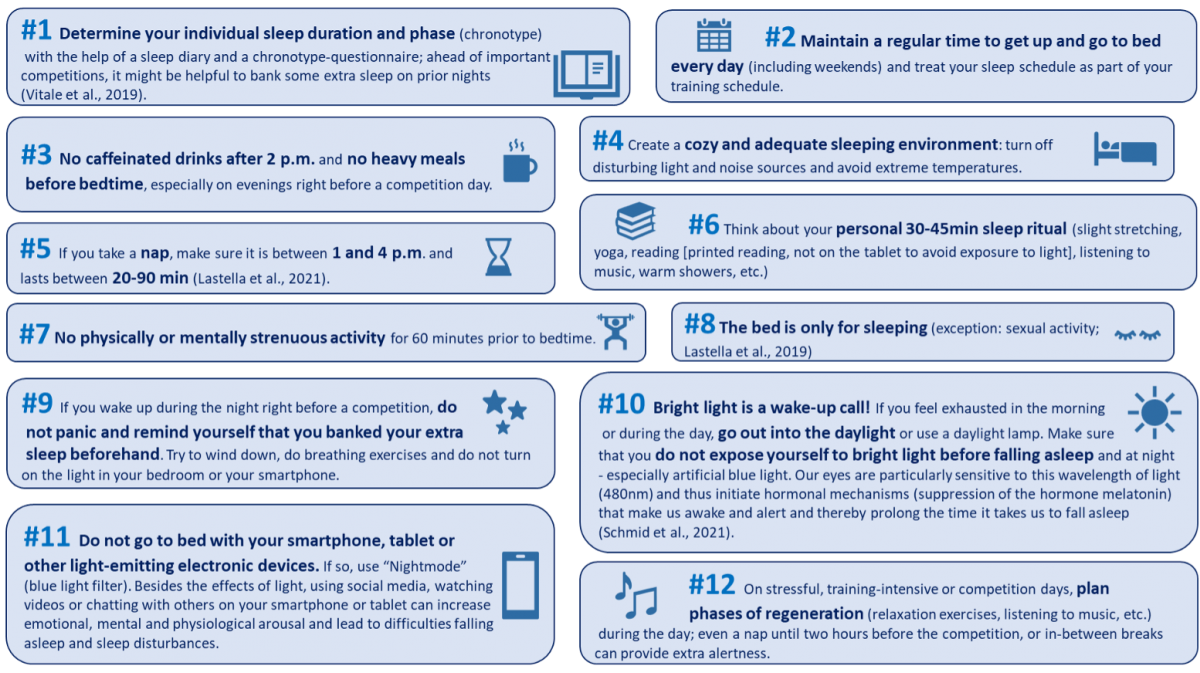

Strategies to improve sleep quality in Olympic athletes

It is worth noting that it has recently been shown that the adoption of individualized sleep hygiene strategies can determine an improvement in total sleep time and a reduction in sleep latency (i.e., the time it takes to fall asleep after bedtime) in Olympic-level athletes [5, 12] (Vitale et al., 2023; Pasquier et al., 2023). The sleep hygiene rules shown in Image 4 should be followed by (Olympic) athletes in particular. If an athlete complains of sleep problems for more than 4 weeks, a doctor should be consulted to screen for organic sleep disorders. If an organic sleep disorder (e.g. sleep-related breathing disorder) is suspected, professional polysomnography in a sleep laboratory is required.

Image 4. Strategies to improve sleep quality in athletes.

Image 4. Strategies to improve sleep quality in athletes.

Bibliography

1] Hirshkowitz, M., Whiton, K., Albert, S. M., Alessi, C., Bruni, O., DonCarlos, L., Hazen, N., Herman, J., Adams Hillard, P. J., Katz, E. S., Kheirandish-Gozal, L., Neubauer, D. N., O'Donnell, A. E., Ohayon, M., Peever, J., Rawding, R., Sachdeva, R. C., Setters, B., Vitiello, M. V., & Ware, J. C. (2015). National Sleep Foundation's updated sleep duration recommendations: Final report. Sleep Health, 1(4), 233–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2015.10.004

[2] Fullagar, H. H. K., Skorski, S., Duffield, R., Hammes, D., Coutts, A. J., & Meyer, T. (2015). Sleep and athletic performance: The effects of sleep loss on exercise performance, and physiological and cognitive responses to exercise. Sports Medicine, 45(2), 161–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-014-0260-0

[3] Lastella, M., Roach, G. D., Halson, S. L., & Sargent, C. (2015). Sleep/wake behaviours of elite athletes from individual and team sports. European journal of sport science, 15(2), 94–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2014.932016

[4] Sargent, C., Lastella, M., Halson, S. L., & Roach, G. D. (2021). How much sleep does an elite athlete need? International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 16, 1746-1757. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34021090/

[5] Vitale, J. A., Borghi, S., Piacentini, M. F., Banfi, G., & La Torre, A. (2023). To Sleep Dreaming Medals: Sleep Characteristics, Napping Behavior, and Sleep-Hygiene Strategies in Elite Track-and- Field Athletes Facing the Olympic Games of Tokyo 2021. International journal of sports physiology and performance, 18(12), 1412–1419. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2023-0144

[6] King, B. R., Hoedlmoser, K., Hirschauer, F., Dolfen, N., & Albouy, G. (2017). Sleeping on the motor engram: The multifaceted nature of sleep-related motor memory consolidation. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 80, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.04.026

[7] Falck, R.S., Stamatakis, E., & Liu-Ambrose, T. (2021). The athlete’s sleep paradox prompts us to reconsider the dose-response relationship of physical activity and sleep. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 55(16), 887-888. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-103835

[8] Matos, N. F., Winsley, R. J., & Williams, C. A. (2011). Prevalence of nonfunctional overreaching/overtraining in young English athletes. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 43(7), 1287–1294. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e318207f87b

[9] Oda, S., & Shirakawa, K. (2014). Sleep onset is disrupted following pre-sleep exercise that causes large physiological excitement at bedtime. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 114(9), 1789–1799. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-014-2873-2

[10] Halson, S. L., Appaneal, R. N., Welvaert, M., Maniar, N., & Drew, M. K. (2021). Stressed and Not Sleeping: Poor Sleep and Psychological Stress in Elite Athletes Prior to the Rio 2016 Olympic Games. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 17(2), 195-202. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2021-0117

[11] Jansen van Rensburg, D. C., Jansen van Rensburg, A., Fowler, P. M., Bender, A. M., Stevens, D., Sullivan, K. O., Fullagar, H. H. K., Alonso, J. M., Biggins, M., Claassen-Smithers, A., Collins, R., Dohi, M., Driller, M. W., Dunican, I. C., Gupta, L., Halson, S. L., Lastella, M., Miles, K. H., Nedelec, M., Page, T., … Botha, T. (2021). Managing Travel Fatigue and Jet Lag in Athletes: A Review and Consensus Statement. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 51(10), 2029–2050. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-021-01502-0

[12] Pasquier, F., Pla, R., Bosquet, L, Sauvet, F, Nedelec., and D-Day Consortium (2023). The Impact of Multisession Sleep-Hygiene Strategies on Sleep Parameters in Elite Swimmers. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 18(11), 1304-1312. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2023-0018

Images

Image 1 & 2: Klaus Trifich DI schreibdemzeichner@klaustrifich.at

Image 3 & 4: created by the authors. Wir haben die Rechte für die Nutzung: „Inkludiert ist das Recht für Nutzung des Werkes für das Projekt und inhaltlich verwandten Zwecken, analog oder digital, ausgehend vom Centre for Cognitive

Neuroscience (CCNS) der Universität Salzburg, Fachbereich Psychologie.“