There is no place like home – How the French crowd may impact the athletes at the Paris 2024 Olympic Games

Editor: Lisa Musculus-Schönenborn

Editorial Assistant: Jana Dreston

This article has also been translated into German and Dutch.

Athletes and fans believe to be superior when competing at home. Will the French believe the same at this year’s Olympics in Paris? We review the psychological explanations for a home advantage and predict that French athletes will perform better at home, but, they are not unbeatable.

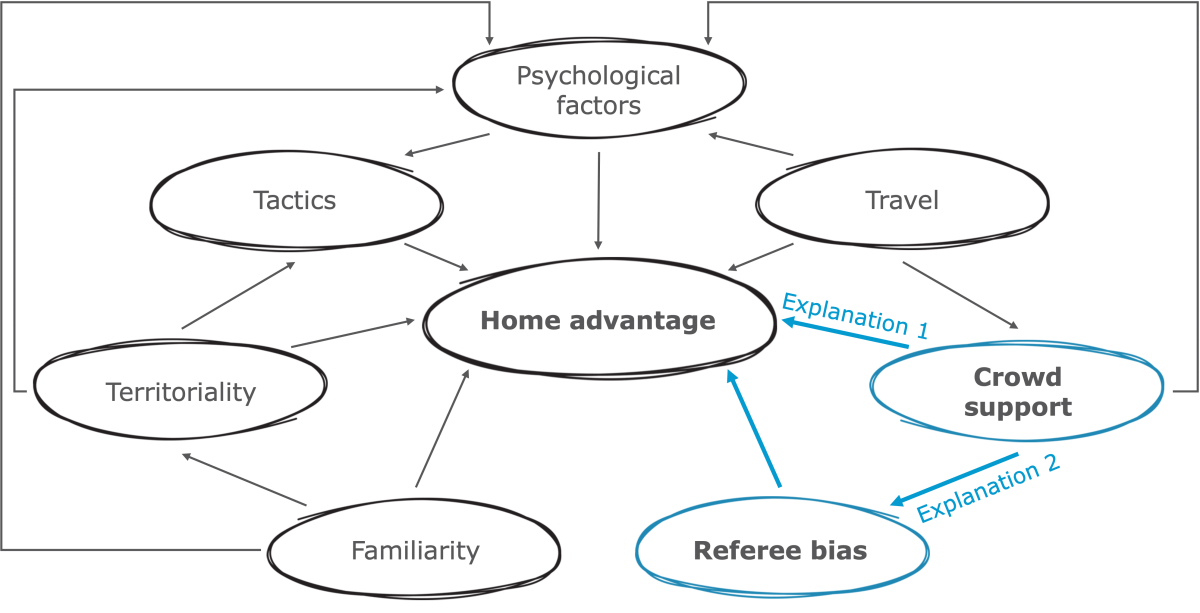

At “her” London Olympics , Jessica Ennis said: “Stepping into the stadium, it blew me away. The crowd was amazing.” [1]. She backed that up with a personal best in the 200m sprint. What she may have experienced is called home advantage: when you are more likely to win at your home stadium. It has been studied for nearly 50 years (summarized in [2]) and is found in many end-of-season tables for team sports, but also in the Olympic Games [3], [4]. Here, a country wins an average of 14 more medals when hosting the Summer Olympics, 7 of which are gold. If you ask an Olympic athlete, they will say this is caused by the home-crowd’s support, but playing at home also lets you be more self-confident and play more offensively.

Image 1. Overview of all medals won by the last 7 countries that hosted the Summer Olympics

Image 1. Overview of all medals won by the last 7 countries that hosted the Summer Olympics

Will the French athletes therefore win more medals than at previous Games? In Tokyo 2020, they won 33 medals, 10 of them gold. At that time, the COVID-19 pandemic was raging, there were no spectators and every competition was held in silence. Nonetheless, Japan still appeared to have a home advantage, as did the countries who previously hosted. In the year each country hosted the Summer Olympics (bold bar), they did better than usual (dotted line).

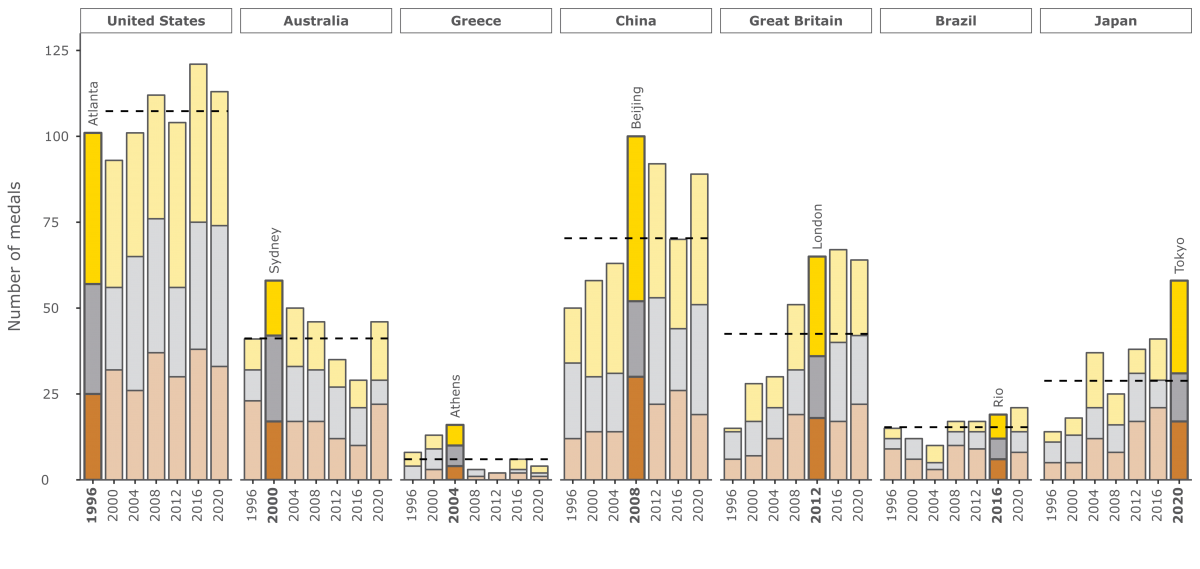

Why does a home advantage exist?

Possible reasons for the home advantage were already published 30 years ago [5] or more recently [6], [7]. One of the most prominent models identifies seven reasons, each of which could explain home advantage [8]. These reasons are not independent: The arrows between the seven reasons show which factors have been empirically found to affect other factors in previous studies until 2005. For example, the home crowd’s support might improve the psychological state of the home team, that is, their self-confidence. With that, the team might employ a more offensive tactic.

Numerous studies have collected the match results from league archives and looked at the effect of the following factors on the outcome of the match:

- Travel factors (e.g., ease of travel, time zone change, length of journey)

- Competition rules (e.g., seeding lists, home team selection options)

- Facility Familiarity (e.g., grass pitch or artificial turf, size, location, and altitude of the facility)

- Tactical decisions (e.g., coaches choose more offensive plays when at home vs. defensive when competing away).

- Psychological factors of the players (such as self-fulfilling prophecies, stereotype threat, self-confidence, aggressive style of play)

- Physiological

factors of the players (e.g., higher testosterone or

cortisol levels, an animal instinct of territoriality, that increases aggressive behavior)

However, most studies, have focused on two explanations: (1) that spectators support the home team and put pressure on the away team, and (2) that referees are biased by spectators.

Explanation 1: Spectators cause home advantage.

The influence of spectators is often considered the key determinant of home advantage: a vocal crowd supporting the home team/athletes is assumed to improve performance. This is called the

social support hypothesis. To find out whether the spectators help the home team win, we could compare 100 matches without spectators with 100 matches with many spectators and see how often the home team wins in each situation. If they win more often with spectators present, we might assume that they played a positive role. However, when conducting such an experiment, we need to control for all other potential effects (e.g., the skill level of each team). This is rarely possible with data from league archives.

You might have experienced a positive effect of spectators yourself, such as increased motivation, enjoyment, and excitement. Participants reported these feelings after two cycling practices while receiving encouraging feedback [9]. Higher motivation and effort are especially good when performance depends on how much energy you put in, for example at a 5k-run. Additionally, the away athletes might receive negative calls from the home crowd, and experience the opposite: decreased motivation, high pressure, less enjoyment.

Sometimes a supportive, cheering crowd can also lead to a drop in performance because the high expectations of all the hyped-up spectators are too much pressure. This is called the social pressure hypothesis, which can cause choking under pressure [10]. Imagine you are playing in the Champions League, you take the deciding penalty kick, and there are hundreds of fans in front of you expecting you to win the game for them. That is a lot of pressure, which can cause a distraction from the task, or too much focus on executing the skill, and suddenly you miss the

goal by a meter. These attention effects (either too much or too little) are especially bad for performance in cognitive tasks, such as aiming at a target. A recent study showed that male biathletes run faster laps in the presence of spectators then when they are alone, but also shoot less accurately [11]. Interestingly, the opposite trend was found for female biathletes.

If researchers [11] had not separated the data by gender, they would not have found any spectator effect. This is called the no influence hypothesis: some studies do not find a “more spectators – more home wins” relationship, or if they do, it is very weak, more like a “more spectators – slightly more home wins”. Overall, spectators can have a positive, but it can also have a negative effect or no influence at all. Thus, they cannot be the only reason for the consistent home advantage – other factors must play a role.

Explanation 2: Referees cause home advantage.

Referees can make wrong or biased decisions, which could affect the home advantage. How? Referees make decisions all the time: was it a foul; how bad was it; how good was the gymnastics routine. It turns out that those judgements often favor the home athletes. Data from the Summer Olympics from 1896 to 1996 show that in sports with subjective judgements (e.g., gymnastics, diving), the home athletes received more points, while in objective sports without judgements (e.g., track and

field, weightlifting) the away team actually had an advantage [3]. In football, the home team receives fewer yellow or red cards, and injury time is shorter when the home team is ahead one

goal than when the away team is ahead by one

goal, which is interpreted as a bias in favor of the home team, to increase their chance of winning.

Interestingly, this difference between home and away football teams seemed to disappear during the COVID-19 pandemic. Researchers suggested that the spectators not only influence the match directly, but also the referees, who in turn change the course of the match. Think back to the last time you saw an ambiguous foul against the home team. Did the home crowd start shouting and booing, and did the referee finally give the away team a warning? The referee may have perceived the increased noise from the crowd as a

cue to decide in their favor [12]. This bias has been repeatedly demonstrated in experimental studies, but whether it has an influence on the level of the home advantage is doubtful [7].

What if it is not the spectators?

Athletes seem to learn early on that playing at home with “your” crowd is better. This may be a socialization to believe in a spectator-driven home advantage. During COVID-19, when games were played without spectators, the home advantage did not disappear completely. So, what if it is not the spectators? There are a few other factors that seem to explain a home advantage at the Olympics:

- Financial resources: countries that host the Olympic Games, invest in their sporting systems years before the actual event. Take London 2012: UK sport received more than £200 million in funds before Beijing 2008 and another £208 million before London 2012 for research, medicine, and facilities [13].

- Biased selection process: who would you give the Olympic Games to? A country that just won its first medal ever last year, or a country that often ranks in the top 20? Probably the latter, but that means that the host countries are already quite good. But! This does not explain why a successful county has even more success at home than it usually is abroad.

- Different rules: According to the Olympic Agenda 2020, the host nation can request to add sports (with some restrictions). Tokyo 2020 added Skateboarding, Karate, Surfing and sport climbing, where they won 14 medals (24% of all their medals that year). The host nation is also allowed to have more athletes represented in each sport, which increases the chances of doing well in more events.

While we have focused here on the psychological (dis)advantages of competing at home, we acknowledge that these factors also contribute to the home advantage at the Olympics.

What does this mean for the French athletes?

France has won 33 medals at Tokyo 2020 (10 gold medals). Since 2000, France’s medal share has plateaued. If France experiences the same average benefit from hosting as the other nations since 2000, they could win nearly 50 medals just by competing at home. Here, we have presented evidence that spectators can have a positive, negative, or no effect on athletes, while economists argue that money will decide the Games. We must also remember that the crowd will be international at Paris 2024. Maybe it is worth looking at France’s neighbors and whether they will experience a “close-to-home” advantage?

Image 3. Home Advantage

Image 3. Home Advantage

Despite the studies showing that the presence of spectators results in increased motivation, more enjoyment, and feelings of

social support, it is not 100% sure that the French athletes will do well at their own Olympics because of the spectators. However, since most countries win more medals when they host, we expect that France to do better in 2024 than in 2020 or 2028.

How to prepare for the Olympics? Sport psychologists work with athletes, teams, coaches and referees on mental skills to help them perform at their best. They can assist French athletes, for example, by finding individual strategies to deal with the additional pressure from the crowd on and off the court. Similarly, to ensure the fairness of the Olympics, referees in subjectively judged sports should be aware of the impact of spectators on their decisions and learn to manage their influence. And the rest of the athletes? Just because French athletes are competing at home does not mean they are unbeatable. With their sport psychologists, they can prepare themselves for the large crowds and extraordinary pressure. Not all fans will be cheering only for France and booing everyone else.

Bibliography

[1] J. Doward, “London 2012: Team GB medallists pay tribute to home crowd’s support,” The Guardian, Aug. 05, 2012. Accessed: Feb. 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2012/aug/05/team-gb-medallists-credit-...

[2] M. A. Gómez-Ruano, R. Pollard, and C. Lago-Peñas, Home Advantage in Sport: Causes and the Effect on Performance. Routledge, 2021.

[3] N. J. Balmer, A. M. Nevill, and A. M. Williams, “Modelling home advantage in the Summer Olympic Games,” J. Sports Sci., vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 469–478, 2003, doi: 10.1080/0264041031000101890.

[4] C. Singleton, J. J. Reade, J. Rewilak, and D. Schreyer, “How big is home advantage at the Olympic Games?,” in Research Handbook on Major Sporting Events, Edward Elgar Publishing, 2024, pp. 88–103.

[5] K. S. Courneya and A. V. Carron, “The Home Advantage In Sport Competition: A Literature Review,” J. Sport Exerc. Psychol., vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 13–27, 1992, doi: 10.1123/jsep.14.1.13.

[6] M. Bilalić, B. Gula, and N. Vaci, “Home advantage mediated (HAM) by referee bias and team performance during covid,” Sci. Rep., vol. 11, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Nov. 2021, doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-00784-8.

[7] B. Strauss, K. Staufenbiel, E. van Meurs, and C. MacMahon, “Social influence of sport spectators,” in Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1st ed., J. Schüler, M. Wegner, H. Plessner, and R. C. Eklund, Eds., Springer, 2023, pp. 425–444.

[8] R. Pollard and G. Pollard, “Home advantage in soccer: A review of its existence and causes,” Int. J. Soccer Sci., vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 25–33, 2005.

[9] A. M. Edwards, L. Dutton-Challis, D. Cottrell, J. H. Guy, and F. J. Hettinga, “Impact of active and passive social facilitation on self-paced endurance and sprint exercise: Encouragement augments performance and motivation to exercise,” BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med., vol. 4, no. 1, p. e000368, 2018, doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2018-000368.

[10] R. F. Baumeister, “Choking under pressure: Self-consciousness and paradoxical effects of incentives on skillful performance,” J. Pers. Soc. Psychol., vol. 46, no. 3, pp. 610–620, März 1984, doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.46.3.610.

[11] A. Heinrich, F. Müller, O. Stoll, and R. Cañal-Bruland, “Selection bias in social facilitation theory? Audience effects on elite biathletes’ performance are

gender-specific,” Psychol. Sport Exerc., vol. 55, p. 101943, 2021.

[12] C. Unkelbach and D. Memmert, “Crowd noise as a

cue in referee decisions contributes to the home advantage,” J. Sport Exerc. Psychol., vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 483–498, 2010, doi: 10.1123/jsep.32.4.483.

[13] G. Csurilla and I. Fertő, “The less obvious effect of hosting the Olympics on sporting performance,” Sci. Rep., vol. 13, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Feb. 2023, doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-27259-8.

Images

Image 1: own creation

Image 2: adapted from Pollard, R., & Pollard, G. (2005). Home advantage in soccer: A review of its existence and causes. International Journal of Soccer and Science, 3(1), 25–33.

Image 3: Created using DALL-E, an AI image generation tool by OpenAI.