Can we believe in our own lies?

Can we believe in our own lies? Such a question eventually boils down to the issue of whether lying affects memory. This is particularly relevant in the legal arena, where witnesses, offenders, and suspects adopt deceptive strategies in several situations.

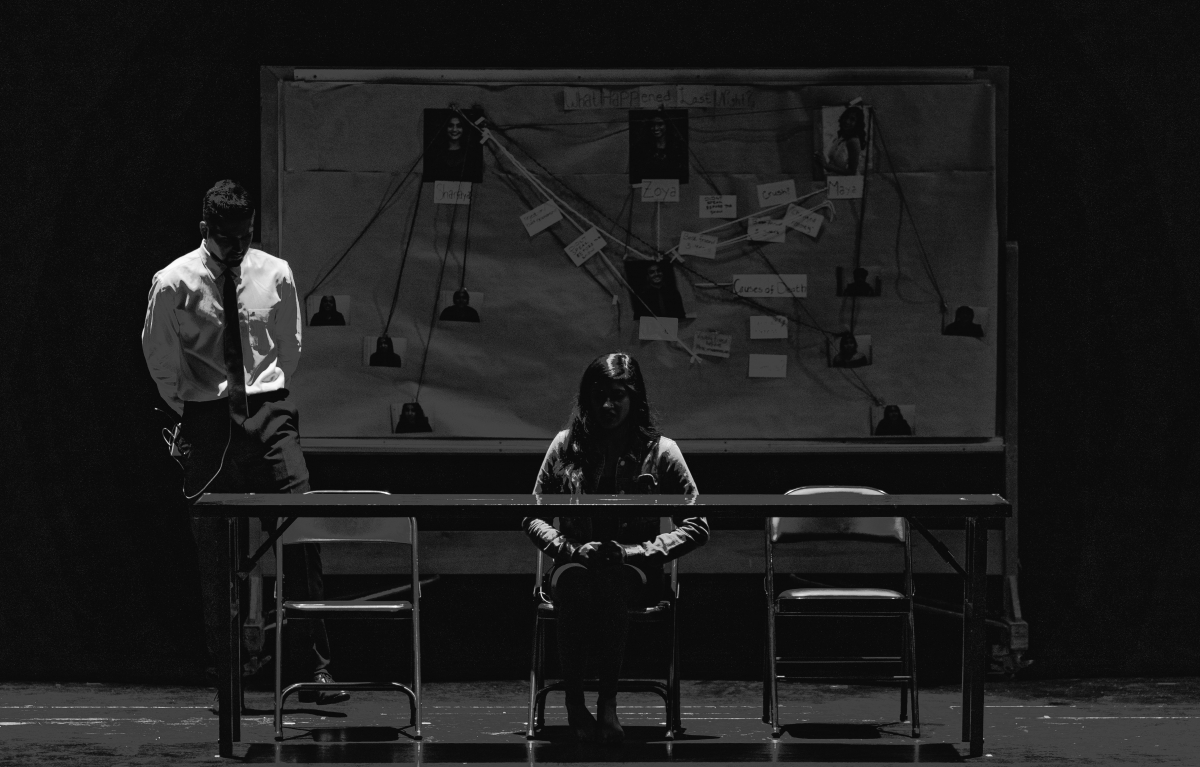

Photo by Martin Lopez from Pexels

Photo by Martin Lopez from Pexels

Introduction

In 1995, Binjamin Wilkormiski published a book entitled Fragments: Memories of a Wartime Childhood 1939-1948. In his book, he described his childhood experience as a survivor of the Holocaust. What seemed to be one of the most emotional and truthful testimonies about one’s vivid memories of experiencing the Holocaust, became one of the most famous cases of falsely fabricating an entire autobiography. Even though Wilkormiski was not a Holocaust survivor, he continued to believe in his own fake autobiography ([1]).

An interesting question here is how Wilkormiski started to believe in his own lie. Taking into the account that after Wilkormiski’s psychological assessment, he was declared incapable of distinguishing the truth from a lie ([2]), one might suggest that Wilkormiski’s lie affected his own memory.

Can the act of intentionally lying affect the memory for the original experience? Despite the large number of studies that have been focused on the formation of memory distortions without intention (e.g., [3]; [4]; [5]), experimental studies on the relationship between lying and memory are limited, especially considering the possible consequences that lying may play into the legal arena. We will address this issue by reviewing recent work on the detrimental mnemonic effects due to the act of lying. More precisely, we will focus on how each deceptive strategy (i.e., false denials, feigned amnesia,and fabrication) can influence memory for (mock) criminal experiences differently, highlighting their underlying mechanisms. Finally, we will elaborate on the implications of such deceptive strategies in the legal domain.

False Denials

Individuals sometimes falsely deny that an event actually took place. Although accusatorial interviews could promote this type of behaviour (e.g., [6]), research suggests that, in some circumstances, suspects falsely deny their involvement in a crime to avoid punishment (e.g.,[7]; [8]), while victims (e.g., sexual abuse victims) falsely deny that they were victimized to do not re-experience the traumatic accident or for the fear of accusing someone (e.g., [9]; [10]; [11]).

One of the first studies about the effects of false denials on memory was by Vieira and Lane (2013)[12]. The authors presented pictures of certain objects (e.g., an apple) and subsequently instructed the participants to describe or deny either studied or unstudied objects. Two days later, they tested participants’ memory through a source memory task wherein an honest report was requested towards all the previously shown studied and unstudied objects. During this recollection task, participants were asked whether the items were studied or unstudied objects and what deceptive strategy they had adopted (i.e., describing vs. denying). Vieira and Lane (2013) found that participants’ memory for studied pictures was affected when having denied such pictures. That is, participants had more difficulty remembering if they had previously studied the pictures when they denied having studied them rather than when they told the truth.

Another recent line of research has shown that falsely denying details of an event impairs memory (e.g., [13]; [14]). The basic procedure in this line of work was the following: Participants saw some stimuli (e.g., pictures, video of a theft) and then they answered some questions about them. The participants were split-up into two groups: truth-tellers and false deniers. Truth-tellers had to answer the questions honestly while the false deniers were instructed to falsely deny each question (e.g., “He did not steal the hat”). After a delay, participants’ memory for the event was tested, meaning that all participants honestly reported what they remembered. Participants had to recollect whether they had seen specific items in the video and whether they had discussed these items during the first interview. The recurring finding is that participants who falsely denied exhibited a memory impairment for details discussed in the interview while the memory for the actual event remained intact. This effect has also been called denial-induced forgetting (DIF; Otgaar et. al, 2016)13.

Subsequent studies have been conducted to extend and replicate the DIF effect by using a mock crime video in children and adults ([15]) and/or using pictures as stimuli ([16]). Moreover, Romeo and colleagues (2019)[17] used a negative virtual reality scene (i.e., airplane crash with dead bodies near the crashed plane) to study the effect of DIF for a traumatic experience and found that false denials can negatively impact memory for the experienced event.

What could be the underpinning mechanism of the denial-induced forgetting effect? One option might be that false denials inhibit memory for the truth. Accordingly, the act of denying details of an experienced event makes such information less likely to be stored in memory, eventually rendering its retrieval more difficult over time ([18]; [19]; [20]).

Feigning Amnesia

Similar memory impairing effects are observed in feigned amnesia, which entails that individuals pretend to suffer from memory loss after experiencing an event (e.g., [21]; [22]). Approximately 30% of individuals feign amnesia following a crime ([23]) in order to try to appear incompetent to stand the trial and obtain benefit (e.g., [24]; [25]; [26]; [27]). Further, when this deceptive strategy is adopted, relevant and genuine information of the event (e.g., crime) can be forgotten ([28]; [29]; [30]; [31]; [32]; [33]).

The standard procedure to examine this memory-undermining effect of feigning amnesia is as follows. Participants typically read a narrative story (e.g., [34]) or view a video of a mock crime (e.g., [35]) with the instructions to recognize themselves as the offender. Then, during the first memory session, they are instructed to either simulate memory loss (i.e., simulators) or confess to the crime (i.e., confessors). One week later, during the final memory session, all participants are requested to genuinely recall the event. Findings show that when asked to give up their role as simulators, simulating participants have poorer memory for the event than confessors (e.g., [36]; [37]; [38]; [39]). Moreover, in some studies a third group of participants is included as a delay test-only condition (i.e., controls). These participants do not receive any instructions during the first memory session. When simulators are compared with controls no statistically significant differences were revealed between these two groups ([40]; [41]). This means that because both simulators and controls do not actually rehearse the mock crime during the first memory phase, they would have at least one less opportunity to store the experience in their memory, resulting in having a weaker final memory performance than confessors. Hence, due to the similar memory performance exhibited by both simulators and controls, some scholars argue that the memory-undermining effect of feigning amnesia might be due to lack of rehearsal (e.g., [42]; [43]; [44]; [45]; [46]).

However, recent studies suggest that individuals can still retain certain information of the crime despite having previously feigned amnesia (e.g., [47]; [48]; [49]). For instance, Mangiulli and colleagues (2019) recently suggested that the negative mnemonic effect on true memory for a crime due to feigned amnesia might be related to retrieval-induced forgetting (i.e., RIF; [50]). RIF refers to the forgetting of related, but not-practiced events ([51]). In the typical RIF procedure, participants have to learn a set of category items pairs (e.g., fruit–apple and drink-gin). In a second phase, they are instructed to practice half of the studied pairs from half of the categories (e.g., fruit–ap_). In a final memory test, participants are asked to recall all the words they can remember from the first phase. The standard finding is that the practised items (e.g., apple) are better recalled than unpractised items from both practiced (e.g., fruit) and unpractised categories (e.g., drink-gin), rendering these latter items more susceptible to forgetting. Similarly, when simulators are asked to specifically omit crucial information of the crime experience during the attempt to feign amnesia (e.g., how the crime occurred), they showed a lower memory performance for that information than for other minor crime-related details (e.g., location of the crime) (e.g., [52]).

Fabrication

Another type of lie that has been shown to affect memory is fabrication. This type of deceptive strategy refers to someone who comes up with an entirely false account for a specific event, for example by providing a false alibi surrounding the criminal event ([53]).

A typical method used in research to study fabrication is the forced confabulation paradigm (e.g., [54]; [55]; [56]). Namely, participants watch a video and they are provided with true and false questions about it. One group is asked to honestly answer what they remember, while a second group has to fabricate (i.e., self-generated) an answer for each question, also when they do not remember the details. One week later, their memory is tested. Results showed that people who fabricated details about the video were more likely to later recall their own fabrications, thereby making errors in their final memory-related statements (i.e., commission errors) (e.g., [57]; [58]; [59]; [60]; [61]). In addition, in 2004 ([62]), Pickel suggested that the undermining effect of fabrication on memory (i.e., more omissions and commissions) takes place just for the fabricated details rather than for the general memory for the experience.

Relatedly, Polage ([63]; [64]) investigated whether the act of fabricating a completely false event can alter one’s beliefs that the fabricated event actually happened. In her studies, participants first completed a questionnaire in which they rated the likelihood that two particular events happened to them (i.e., fabricated-experimental vs. control events). After that, those that indicated that the experimental event was unlikely to have been occurred to them, wrote a false account for it. One-week later, participants rated the likelihood of the events again (i.e., fabricated-experimental vs. control events). Polage (2004)63 found the following results. On the one hand, more than 50% of participants reported lower likelihood ratings for the fabricated event compared to the control event, meaning that participants correctly believed that the fabricated event never happened. On the other hand, a small subset (10-16%) of participants revealed an increased belief in the occurrence of the lied about event. Polage further examined this latter pattern in other studies (64; [65]) wherein she also showed that confabulators increased their beliefs in their lies over time (self-generated events). She argued that fabrication inflation can take place when individuals falsely fabricate an entire event and this effect depends also on individuals differences (e.g., level of discomfort experienced during the lie).

The dominant theoretical framework used to explain the memory impairment related to fabrication is the source monitoring framework (SMF; [66]). According to the SMF, oftentimes actual and imagined events share similar elements, such as perceptual and contextual details. When, for instance, a fabricated (self-generated) account for an experience has many commonalities with the original event, people are prone to confound the two sources (i.e., fabricated vs. original). As a result, those fabricated details can get mixed-in with the original ones, generating source monitoring errors (e.g. [67]; [68]). In other words, this confusion between true-event and false-self generated statements make people more susceptible to memory errors. Furthermore, other studies (e.g., [69]) have shown that people can be able to recognize the correct source of information (i.e., self-generated vs actual) when it is adopted as an implicit measure of source monitoring (i.e. aIAT; [70]; [71]).

The Consequences of Lying on Memory in the Courtroom

Beyond the fact that offenders, witnesses or victims lie about an experienced crime for several reasons, like (i) avoiding culpability, (ii) protecting themselves from re-experiencing traumatic events or (iii) minimizing their involvement, what seems particularly relevant are the possible consequences that can happen when legal professionals (e.g., police, judges) have to deal with eyewitnesses, suspects, victims or offenders that in a first time have lied. Indeed, as illustrated above, when people deliberately lie about criminal experiences (i.e., false denials, feigning amnesia and fabrication), their original memory for those events can be affected when they come forward with the truth.

Undoubtedly, this becomes a primary issue for forensic professionals and judges who have to rely on individuals’ memory-related statements to adequately perform their job. Indeed, having a complete picture of what actually happened could be difficult. However, knowing such mnemonic effects can help to reduce mistakes by legal professionals. For instance, a professional, unaware that fabrication could lead to impairment of the actual memory, could be prone to accept statements made by liars as reliable and true just because they come forward with the truth. Moreover, it could be the case that professionals lacking adequate knowledge could lead to erroneous interrogation trying to unveil information that will never be retrieved due to a genuine impairment of the liar’s memory, like in the case of false deniers.

Therefore, given the fact that lying occurs frequently in the legal arena (e.g., [72]; [73]; [74]; [75]), it is necessary to inform legal and forensic professionals about the effects of lying on memory. Such knowledge could elucidate why Binjamin Wilkormirski started to believe in his own lies.

References

[1] Finkelstein, N. (2000). The Holocaust Industry. Index on Censorship, 29(2), 120-129.

[2] Bertolini, F. (2011). L’identità rubata di Binjamin Wilkomirski in Luoghi d’Europa. Spazio, Genere, Memoria, a cura di M. Casalena, Quaderni di Storicamente, ArchetipoLibri, Bologna.

[3] Anderson, M. C., & Levy, B. (2002). Repression can (and should) be studied empirically. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 6, 502–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1364-6613(02)02025-9

[4] Loftus, E. F. (2005). Planting misinformation in the human mind: A 30-year investigation of the malleability of memory. Learning & Memory, 12, 361–366. https://doi.org/10.1101/lm.94705

[5] Loftus, E. F., & Pickrell, J. E. (1995). The formation of false memories. Psychiatric Annals, 25, 720–725. https://doi.org/10.3928/0048-5713-19951201-07

[6] Vrij, A., & Granhag, P. A. (2012). Eliciting cues to deception and truth: What matters are the questions asked. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 1, 110-117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2012.02.004

[7] Gudjonsson, G. H., Sigurdsson, J. F., & Einarsson, E. (2004). The role of personality in relation to confessions and denials. Psychology, Crime & Law, 10, 125–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160310001634296

[8] Lyon, T. D. (2007). False denials: Overcoming methodological biases in abuse disclosure research. In Child sexual abuse (pp. 51-72). Psychology Press.

[9] Lyon, T. D. (1995). False allegations and false denials in child sexual abuse. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 1, 429-437.

[10] Goodman-Brown, T. B., Edelstein, R. S., Goodman, G. S., Jones, D. P. H., & Gordon, D. S. (2003). Why children tell: A model of children’s disclosure of sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27, 525–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(03)00037-1

[11] Sjöberg, R. L., & Lindblad, F. (2002). Limited disclosure of sexual abuse in children whose experiences were documented by videotape. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159, 312–314. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.312

[12] Vieira, K. M., & Lane, S. M. (2013). How you lie affects what you remember. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 2, 173–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2013.05.005

[13] Otgaar, H., Howe, M. L., Smeets, T., & Wang, J. (2016). Denial-induced forgetting: False denials undermine memory, but external denials undermine belief. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 5, 168–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2016.04.002

[14] Otgaar, H., Romeo, T., Howe, M. L., & Ramakers, N. (2018). Forgetting having denied: The "amnesic" consequences of denial. Memory & Cognition, 46, 520–529. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-017-0781-5

[15] Otgaar, H., Howe, M. L., Memon, A., & Wang, J. (2014). The development of differential mnemonic effects of false denials and forced confabulations. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 32, 718–731. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2148

[16] Otgaar, H., Howe, M. L., Smeets, T., & Wang, J. (2016). Denial-induced forgetting: False denials undermine memory, but external denials undermine belief. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 5, 168–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2016.04.002

[17] Romeo, T., Otgaar, H., Smeets, T., Landstrom, S., & Boerboom, D. (2019). The impact of lying about a traumatic virtual reality experience on memory. Memory & Cognition, 47, 485- 495. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-018-0885-6

[18] Anderson, M. C., & Huddleston, E. (2012). Towards a cognitive and neurobiological model of motivated forgetting. In True and false recovered memories (pp. 53-120). Springer, New York, NY. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-1195-6_3

[19] Anderson, M. C., & Neely, J. H. (1996). Interference and inhibition in memory retrieval. In E. L. Bjork & R. A. Bjork (Eds.), Memory: Handbook of perception and cognition (2nd ed., pp. 237–313). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-012102570-0/50010-0

[20] Anderson, M. C., & Levy, B. (2002). Repression can (and should) be studied empirically. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 6, 502–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1364-6613(02)02025-9

[21] Christianson, S. A., & Bylin, S. (1999). Does simulating amnesia mediate genuine forgetting for a crime event? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 13, 495–511. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1099-0720(199912)13:6<495::aid-acp615>3.0.co;2-0

[22] Van Oorsouw, K., & Merckelbach, H. (2004). Feigning amnesia undermines memory for a mock crime. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 18, 505–518. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.999

[23] Pyszora, N. M., Barker, A. F., & Kopelman, M. D. (2003). Amnesia for criminal offences: a study of life sentence prisoners. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry, 14, 475-490. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789940310001599785

[24] Cima, M., Merckelbach, H., Hollnack, S., & Knauer, E. (2003). Characteristics of psychiatric prison inmates who claim amnesia. Personality and Individual Differences, 35, 373–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00199-X

[25] Tysse, J. E. (2005). Note: The right to an imperfect trial—Amnesia, malingering, and competency to stand trial. William Mitchell Law Review, 32, 353.

[26] Tysse, J. E., & Hafemeister, T. L. (2006). Amnesia and the determination of competency to stand trial. Developments in Mental Health Law, 25, 65–80.

[27] Smith, D., & Resnick, P. (2007). Amnesia and competence to stand trial. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 35, 541–543.

[28] Christianson, S. A., & Bylin, S. (1999). Does simulating amnesia mediate genuine forgetting for a crime event? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 13, 495–511. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1099-0720(199912)13:6<495::aid-acp615>3.0.co;2-0

[29] Bylin, S. (2002). How does repeated simulation of memory impairment affect genuine memory performance? Psychology. Crime & Law, 8, 265–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160208401819

[30] Christianson, S. A., & Bylin, S. (1999). Does simulating amnesia mediate genuine forgetting for a crime event? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 13, 495–511. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1099-0720(199912)13:6<495::aid-acp615>3.0.co;2-0

[31] Van Oorsouw, K., & Merckelbach, H. (2004). Feigning amnesia undermines memory for a mock crime. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 18, 505–518. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.999

[32] Van Oorsouw, K., & Merckelbach, H. (2006). Simulating amnesia and memories of a mock crime. Psychology, Crime & Law, 12, 261–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160500224477

[33] Sun, X., Punjabi, P. V., Greenberg, L. T., & Seamon, J. G. (2009). Does feigning amnesia impair subsequent recall? Memory & Cognition, 37, 81–89. https://doi.org/10.3758/MC.37.1.81

[34] Bylin, S., & Christianson, S. Å. (2002). Characteristics of malingered amnesia: Consequences of withholding vs. distorting information on later memory of a crime event. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 7, 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1348/135532502168379

[35] Mangiulli I., van Oorsouw K., Curci A., Merckelbach H., & Jelicic, M. (2018). Feigning amnesia moderately impairs memory for a mock crime video. Frontiers in Psychology, 9:625. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00625

[36] Christianson, S. A., & Bylin, S. (1999). Does simulating amnesia mediate genuine forgetting for a crime event? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 13, 495–511. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1099-0720(199912)13:6<495::aid-acp615>3.0.co;2-0

[37] Mangiulli I., van Oorsouw K., Curci A., Merckelbach H., & Jelicic, M. (2018). Feigning amnesia moderately impairs memory for a mock crime video. Frontiers in Psychology, 9:625. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00625

[38] Van Oorsouw, K., & Giesbrecht, T. (2008). Minimizing culpability increases commission errors in a mock crime paradigm. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 13, 335–344. https://doi.org/10.1348/135532507X228539

[39] Van Oorsouw, K., & Merckelbach, H. (2004). Feigning amnesia undermines memory for a mock crime. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 18, 505–518. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.999

[40] Sun, X., Punjabi, P. V., Greenberg, L. T., & Seamon, J. G. (2009). Does feigning amnesia impair subsequent recall? Memory & Cognition, 37, 81–89. https://doi.org/10.3758/MC.37.1.81

[41] Van Oorsouw, K., & Merckelbach, H. (2004). Feigning amnesia undermines memory for a mock crime. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 18, 505–518. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.999

[42] Christianson, S. A., & Bylin, S. (1999). Does simulating amnesia mediate genuine forgetting for a crime event? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 13, 495–511. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1099-0720(199912)13:6<495::aid-acp615>3.0.co;2-0

[43] Bylin, S. (2002). How does repeated simulation of memory impairment affect genuine memory performance? Psychology. Crime & Law, 8, 265–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160208401819

[44] Bylin, S., & Christianson, S. Å. (2002). Characteristics of malingered amnesia: Consequences of withholding vs. distorting information on later memory of a crime event. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 7, 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1348/135532502168379

[45] Van Oorsouw, K., & Merckelbach, H. (2004). Feigning amnesia undermines memory for a mock crime. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 18, 505–518. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.999

[46] Van Oorsouw, K., & Merckelbach, H. (2006). Simulating amnesia and memories of a mock crime. Psychology,Crime & Law, 12, 261–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160500224477

[47] Mangiulli, I., Van Oorsouw, K., Curci, A., & Jelicic, M. (2019). Retrieval-induced forgetting in the feigning amnesia for a crime paradigm. Frontiers in Psychology, 10 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00928

[48] Mangiulli I., van Oorsouw K., Curci A., Merckelbach H., & Jelicic, M. (2018). Feigning amnesia moderately impairs memory for a mock crime video. Frontiers in Psychology, 9:625. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00625

[49] McWilliams, Goodman, Lyons, Newton, &Avila-Mora, E., 2014 Memory for child sexual abuse information: simulated memory error and individual differences. Mem. & Cogn. 42, 151–163 https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-013-0345-2

[50] Anderson, M. C., Bjork, R. A., & Bjork, E. L. (1994). Remembering can cause forgetting: Retrieval dynamics in long-term memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 20, 1063–1087. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.20.5.1063

[51] Anderson, M. C., Bjork, R. A., & Bjork, E. L. (1994). Remembering can cause forgetting: Retrieval dynamics in long-term memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 20, 1063–1087. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.20.5.1063

[52] Mangiulli I., van Oorsouw K., Curci A., Merckelbach H., & Jelicic, M. (2018). Feigning amnesia moderately impairs memory for a mock crime video. Frontiers in Psychology, 9:625. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00625

[53] Chrobak, Q. M., & Zaragoza, M. S. (2008). Inventing stories: Forcing witnesses to fabricate entire fictitious events leads to freely reported false memories. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 15, 1190–1195. https://doi.org/10.3758/pbr.15.6.1190

[54] Ackil, J. K., & Zaragoza, M. S. (1998). Memorial consequences of forced confabulation: Age differences in susceptibility to false memories. Developmental Psychology, 34, 1358–1372. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.34.6.1358

[55] Ackil, J. K., & Zaragoza, M. S. (2011). Forced fabrication versus interviewer suggestions: Differences in false memory depend on how memory is assessed. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 25, 933–942.https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1785

[56] Zaragoza, M. S., Payment, K. E., Ackil, J. K., Drivdahl, S. B., & Beck, M. (2001). Interviewing witnesses: Forced confabulation and confirmatory feedback increase false memories. Psychological Science, 12, 473–477. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00388

[57] Ackil, J. K., & Zaragoza, M. S. (2011). Forced fabrication versus interviewer suggestions: Differences in false memory depend on how memory is assessed. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 25, 933–942.https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1785

[58] Chrobak, Q. M., & Zaragoza, M. S. (2008). Inventing stories: Forcing witnesses to fabricate entire fictitious events leads to freely reported false memories. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 15, 1190–1195. https://doi.org/10.3758/pbr.15.6.1190

[59] Chrobak, Q. M., & Zaragoza, M. S. (2012). The misinformation effect. In A. M. Ridley, F. Gabbert, & D. J. La Rooy (Eds.), Suggestibility in legal contexts: Psychological research and forensic implications (pp. 21–44). London: Wiley Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118432907.ch2

[60] Van Oorsouw, K., & Giesbrecht, T. (2008). Minimizing culpability increases commission errors in a mock crime paradigm. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 13, 335–344. https://doi.org/10.1348/135532507X228539

[61] Zaragoza, M. S., Payment, K. E., Ackil, J. K., Drivdahl, S. B., & Beck, M. (2001). Interviewing witnesses: Forced confabulation and confirmatory feedback increase false memories. Psychological Science, 12, 473–477. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00388

[62] Pickel, K. (2004). When a lie becomes the truth: The effects of self-generated misinformation on eyewitness memory. Memory, 12, 14–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210244000072

[63] Polage, D. C. (2004). Fabrication deflation? The mixed effects of lying on memory. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 18, 455–465. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.995

[64] Polage, D. C. (2012). Fabrication inflation increases as source monitoring ability decreases. Acta Psychologica, 139, 335–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2011.12.007

[65] Polage, D. C. (2018) Liar, liar: Consistent lying decreases belief in the truth. Applied Cognitive Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3489

[66] Johnson, M. K., Raye, C. L., Foley, H. J., & Foley, M. A. (1981). Cognitive operations and decision bias in reality monitoring. American Journal of Psychology, 94, 37–64. https://doi.org/10.2307/1422342

[67] Johnson, M. K., Hashtroudi, S., & Lindsay, D. S. (1993). Source monitoring. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 3–28. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.114.1.3

[68] Johnson, M. K., Raye, C. L., Foley, H. J., & Foley, M. A. (1981). Cognitive operations and decision bias in reality monitoring. American Journal of Psychology, 94, 37–64. https://doi.org/10.2307/1422342

[69] Mangiulli, I., Lanciano, T., Jelicic, M., van Oorsouw, K., Battista, F., & Curci, A. (2018a). Can implicit measures detect source information in crime-related amnesia? Memory 26, 1019-1029. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2018.1441421

[70] Greenwald, A. G., Nosek, B. A., & Banaji, M. R. (2003). Understanding and using the implicit association test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 197–216. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.197

[71] Sartori, G., Agosta, S., Zogmaister, C., Ferrara, S. D., & Castiello, U. (2008). How to accurately detect autobiographical events. Psychological Science, 19, 772–780. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02156.x

[72] Block, S. D., Shestowsky, D., Segovia, D. A., Goodman, G. S., Schaaf, J. M., & Alexander, K. W. (2012). “That never happened”: Adults’ discernment of children’s true and false memory reports. Law and Human Behavior, 36, 365–374. https://doi:10.1037/h0093920

[73] Chrobak, Q. M., & Zaragoza, M. S. (2008). Inventing stories: Forcing witnesses to fabricate entire fictitious events leads to freely reported false memories. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 15, 1190–1195. https://doi.org/10.3758/pbr.15.6.1190

[74] Goodman-Brown, T. B., Edelstein, R. S., Goodman, G. S., Jones, D. P. H., & Gordon, D. S. (2003). Why children tell: A model of children’s disclosure of sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27, 525–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(03)00037-1

[75] Pyszora, N. M., Barker, A. F., & Kopelman, M. D. (2003). Amnesia for criminal offences: a study of life sentence prisoners. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry, 14, 475-490. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789940310001599785