Is there an art center in our brain? That’s bananas!

Artworks can move us deeply. But does that mean our brain treats them in a special way? We can find out by looking at how the brain processes art and what evolutionary advantages it has to be able to like things and judge them as beautiful.

Note: This article was already reviewed and is published in the German version of In-Mind.  Picture 1. Viewing Thomas Wilmer Dewing‘s „The Piano “ (with reference to Thomas Baumgärtel‘s spray banana)

Picture 1. Viewing Thomas Wilmer Dewing‘s „The Piano “ (with reference to Thomas Baumgärtel‘s spray banana)

When the artist Maurizio Cattelan unveiled his latest artwork at Art Basel 2019 in Miami Beach, a lot of discussion ensued. The work “Comedian“, was a simple banana that he had taped to a wall. It was sold for an impressive 120,000$ [1]! Cattelan is not the first artist who brought an everyday object into an exhibition. Marcel Duchamp founded the art style Ready-made, which elevates objects from our daily lives into artworks by signing them with the artist’s name or putting them in an exhibition. He presented the pissoir “Fountain” as artwork at the 1917 exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists [2]. It is not uncommon for such artworks to provoke controversy about what art is and what functions it should serve.

You may have experienced an illustration, painting, or movie sparking awe, goosebumps, or even disgust in you before. Artworks are often seen as outstanding because they evoke such strong emotions in us compared to ordinary objects in our environment. It is not far-fetched to think that our brains must also have special structures to process art, which differ from those that recognize everyday objects such as stones, desks, or hats. Otherwise, we wouldn’t have such a strong reaction, would we? But is this really true? To get to the bottom of this, we need to look at what our brains actually do when we look at art.

Art processing step-by-step

Artworks such as paintings are processed by our brains in a stepwise fashion. You can compare this to climbing a ladder: On the lowest rung, the individual components of the picture are processed, meaning that we first have to perceive what is depicted. In the middle of the ladder, we make sense of it, i.e. the brain decides what these building blocks together represent. At the top of the ladder, we solve complex tasks that involve deep thinking, e.g. we judge whether we know the art style or interpret the contents of the picture [3]. Let’s take a closer look at this.

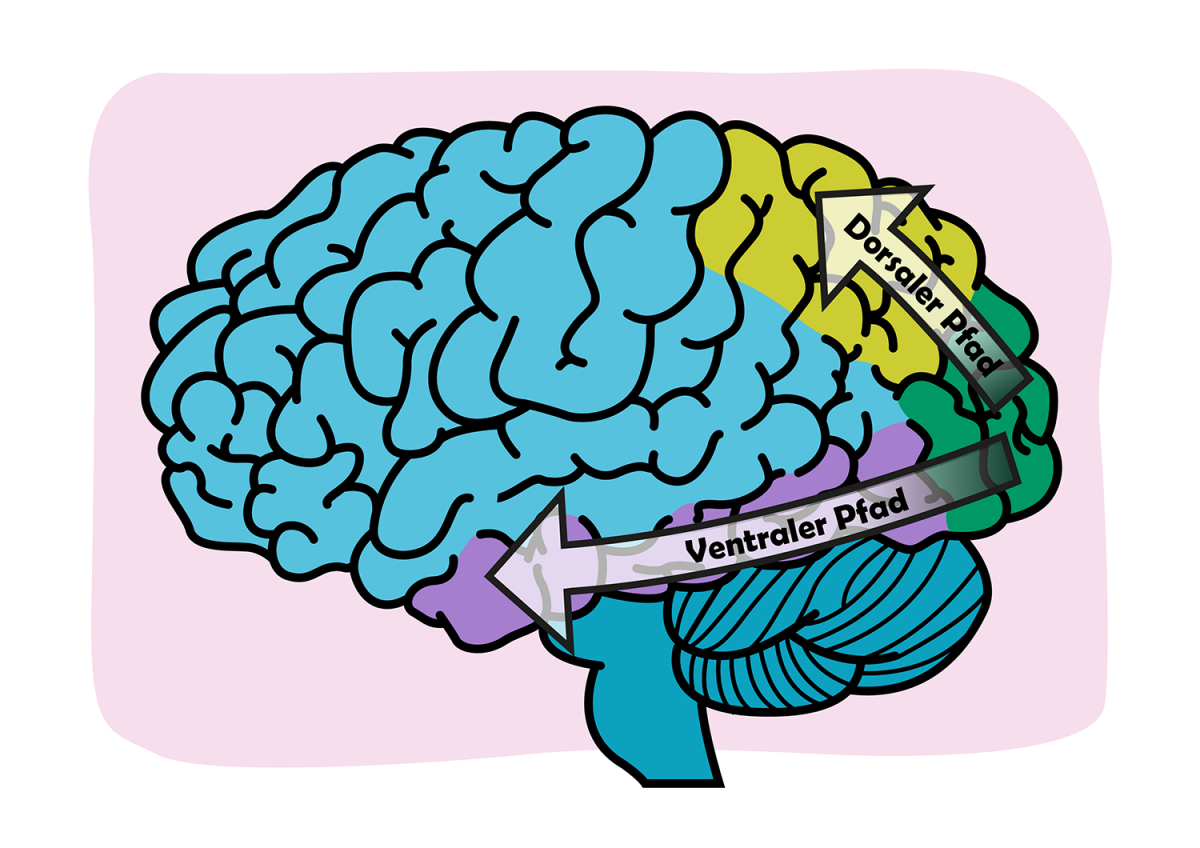

To make sense of our environment, we must first perceive it. This is just as true for everyday objects as it is for artworks. First, photons reflected from the painting enter our eyes. There they are registered by special cells, the photoreceptors of our retina [4]. Those send a signal via the optic nerve to the visual cortex, a region of the brain that processes visual impressions. Afterward, two different neural networks begin to analyze the features of the painting. The first network is the ventral stream, also known as the “what pathway”. It registers the shape and color of what is depicted. On the other hand, the dorsal stream, also known as the “where pathway”, deals with light, position, and movement [5, see picture 2].

Picture 2. Dorsal and ventral streams

Picture 2. Dorsal and ventral streams

It is not important what kind of object we are looking at: Our brain activates both pathways regardless of whether we are holding a fork in our hands while doing the dishes, looking at a flower in the park, or choosing a T-shirt for the day.

At this stage, many things can influence whether or not we like artworks and everyday objects: For example, matters whether these are visually clear and easy to decipher, or whether they have a strong foreground-background contrast [6]. We are fast at identifying symmetries in pictures because symmetrical objects have many visual redundancies, similar to a mirror image. In other words, we have to process less information to perceive them. People judge symmetric artworks and even faces as more beautiful because they are easier for our brains to discern [7]. Shape can be important as well: On average, people like round shapes better than pointy ones [8].

But in these first processing steps, our brain has not yet made sense of the painting. In the second step, it must group and categorize the elements, so that it can make sense from of what it has seen. Lines, dots, and patches of color on the painting are now interpreted as belonging together or being separate, so that we understand that we are not looking at a collection of shapes, but e.g. a portrait. These processes are described by the so-called Gestalt principles, which help our brain put together objects from single parts. For example, the principle of proximity states that shapes that are closer together are perceived to belong to each other. The principle of similarity says that we group elements together if they are alike, e.g. when they have the same color [9].

How average or prototypical an object is for its category also plays a role. For example, what comes to your mind when you hear the word “chair”? Probably a classical chair with four legs. It is less likely a seating opportunity that looks like the one portrayed in picture 3 [10].

Picture 3. The excentric chair

Picture 3. The excentric chair

We also prefer more prototypical objects and paintings. Many people even find average faces more attractive [3]. It also makes a difference whether paintings depict things the way they usually appear in our environment, e.g. we like it better when a painting shows a big elephant and a small mouse. A giant mouse next to a tiny elephant would be a lot more frightening. This phenomenon is called the Ecological Bias [6]. All these processes happen not only with art, but also with everyday objects.

On top, our brain activates regions that help us to focus our attention and lead to introspection, i.e. to deal with our inner thoughts, ourself, and our mental processes. For example, the Default Mode Network is involved when we look at art that is moving to us [11]. When this network is activated, we ignore distractions from the outside world. We focus on our feelings about the artwork, compare them to our experiences, or draw personal conclusions about the depictions. At the same time, the neural network for memory processes judges whether we have seen the artwork before. It determines whether we know the art style or the artist and whether the painting reminds us of things we have experienced in our personal lives [3]. We tend to like familiar things more. Scientists call this the Mere Exposure Effect [12].

In addition, we like artworks more when they are easier for our brain to process, both at the level of perception and the level of thinking [ Processing Fluency Theory; 13]. It is not only important whether the paintings are symmetrical or familiar, but also whether we can easily understand their contents. This is more difficult with abstract paintings than with representative ones. This is especially true for art novices. Art experts are much more familiar with different art styles and can recognize and understand the features and contents of artworks much faster. That is why it is much easier for them to understand complex and abstract paintings and why they often end up liking them better [3]. Even such deep processes happen for both artworks and everyday objects, e.g. we judge texts and statements as more true when we understand them faster [13]. Regardless of whether they actually are!

But these processes are not the end of judging art. How we judge art also depends on our interactions with the outside world. For example, our discussions with friends about the artworks influence whether or not we like them. Further, the culture and political system we live in and the socioeconomic class we belong to play a role [3], because these background experiences also influence how we judge art.

While all these steps are happening, the emotional network of our brain constantly assesses how we feel while we look at and judge the art [3], [11]. Even our reward system is active: We experience pleasure when we look at paintings, when we successfully understand the depiction, or when we have a good discussion about the artwork with others [11].

Two ways of art appreciation

In the end, two reactions result from the interplay of all these different processes: aesthetic judgment and aesthetic emotion. The aesthetic judgment results from all the processes of our perception and thinking about the artwork. The aesthetic emotion is more about the above-mentioned pleasure. In other words, we can understand that the painting is well composed, that it represents the art style well, or that other people will like it. At the same time, this does not mean that we are personally moved by it. A dash of personal taste is always a factor when we judge human-made objects [3], [14].

Why do we appreciate art so much then?

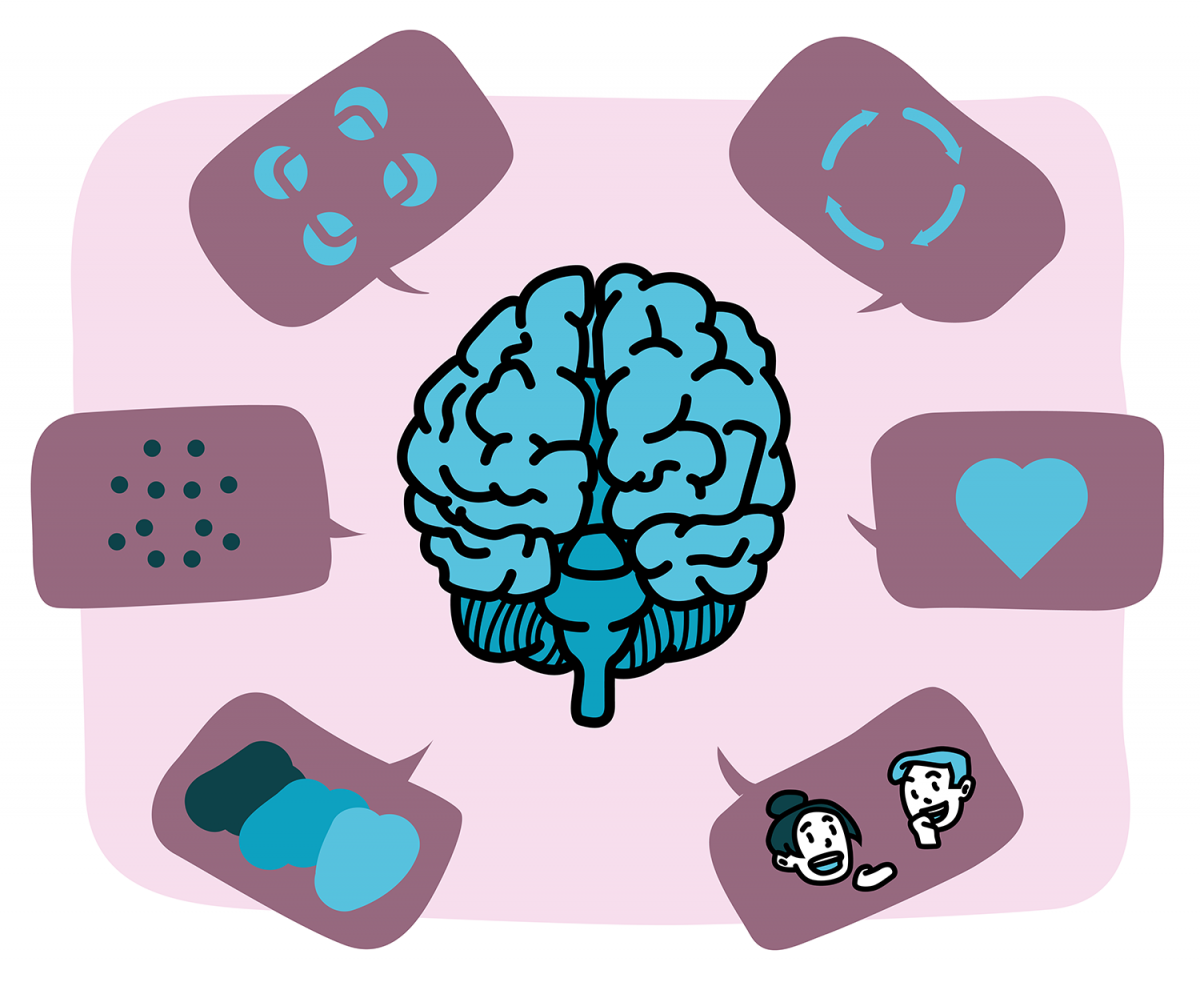

So there is no special “art center” in our brain! Instead, it uses a complex network of brain regions to decide whether we like an artwork or not, which at the same time manages a many of our everyday tasks [11], [15]. In addition,

factors in our environment can influence whether we appreciate art. For this reason, even everyday objects can be seen as artworks when placed in the right context. As in the case of Ready-made! Picture 4. Aesthetic appreciation is complex

Picture 4. Aesthetic appreciation is complex

This makes a lot of sense when you consider that our ability to judge things aesthetically is a byproduct of our evolutionary development. Our ancestors used it to navigate their environment, avoid danger, and find safe food to eat. For example, we judge pointy objects in our environment to be more dangerous than round ones, and color can be used to distinguish between ripe and unripe fruits. Scientists also believe that aesthetics can serve as a cue to find healthy mates for reproduction. Aesthetics could also be used to signal one’s position in the social hierarchy of the group to which one belongs. But it also had meaning in our rituals [5].

All in all, our brains do not distinguish between processing art and processing everyday objects. So why do we appreciate art so much then? Art production is a behavior that requires great mastery: Artists spend years honing their skills. This includes carefully observing their environment, overcoming illusions and delusions about what things look like, as well as training their hands’ motor skills and creativity [16]. We see art as special not because we have a biological antenna for it, but because we have culturally decided to value this dedication and hard work. So the next time someone tries to tell you at a party that they are someone really special because they can paint, take it with a pinch of skepticism: They might just be trying to troll you with a banana.

Bibliography

[1] S. Cascone, „Maurizio Cattelan Is Taping Bananas to a Wall at Art Basel Miami Beach and Selling Them for $120,000 Each“, Artnet News. Zugegriffen: 3. August 2022. [Online]. Verfügbar unter: https://news.artnet.com/market/maurizio-cattelan-banana-art-basel-miami-....

[2] Duchamp, Marcel, Fountain. 1917.

[3] H. Leder, B. Belke, A. Oeberst, and D. Augustin, „A model of aesthetic appreciation and aesthetic judgments“, Br. J. Psychol., Bd. 95, Nr. 4, S. 489–508, 2004, doi: 10.1348/0007126042369811.

[4] N. R. Carlson, Physiology of Behavior. Allyn & Bacon, 2010. [Online]. Verfügbar unter: https://books.google.de/books?id=BXzHjwEACAAJ.

[5] A. Chatterjee, „Neuroaesthetics: A coming of age story“, J. Cogn. Neurosci., Bd. 23, Nr. 1, S. 53–62, Jan. 2011, doi: 10.1162/jocn.2010.21457.

[6] S. E. Palmer, K. B. Schloss, and J. Sammartino, „Visual aesthetics and human preference“, Annu. Rev. Psychol., Bd. 64, S. 77–107, 2013, doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100504.

[7] P. A. van der Helm, „Symmetry perception“, in The Oxford Handbook of Perceptual Organization, J. Wagemans, Hrsg., Oxford University Press, 2015. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199686858.013.056.

[8] M. Bar and M. Neta, „Humans prefer curved visual objects“, Psychol. Sci., Bd. 17, S. 645–648, 2006, doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01759.x.

[9] J. Wagemans u. a., „A century of Gestalt psychology in visual perception: I. Perceptual grouping and figure–ground organization“, Psychol. Bull., Bd. 138, S. 1172–1217, 2012, doi: 10.1037/a0029333.

[10] E. Rosch, Principles of categorization. in Foundations of cognitive psychology: Core readings. Cambridge, MA, US: MIT Press, 2002, S. 270.

[11] E. A. Vessel, „Neuroaesthetics“, in Encyclopedia of Behavioral Neuroscience, 2nd edition (Second Edition), S. Della Sala, Hrsg., Oxford: Elsevier, 2022, S. 661–670. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-809324-5.24104-7.

[12] R. B. Zajonc, „Mere exposure: A gateway to the subliminal“, Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci., Bd. 10, S. 224–228, 2001, doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.00154.

[13] R. Reber, N. Schwarz, and P. Winkielman, „Processing fluency and aesthetic pleasure: is beauty in the perceiver’s processing experience?“, Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev., Bd. 8, Nr. 4, S. 364–382, 2004, doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0804_3.

[14] E. A. Vessel, N. Maurer, A. H. Denker, and G. G. Starr, „Stronger shared taste for natural aesthetic domains than for artifacts of human culture“, Cognition, Bd. 179, S. 121–131, Okt. 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2018.06.009.

[15] M. Skov and M. Nadal, „A Farewell to Art: Aesthetics as a Topic in Psychology and Neuroscience“, Perspect. Psychol. Sci., Bd. 15, Nr. 3, S. 630–642, Mai 2020, doi: 10.1177/1745691619897963.

[16] D. J. Cohen and S. Bennett, „Why can’t most people draw what they see?“, J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform., Bd. 23, Nr. 3, S. 609–621, 1997, doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.23.3.609.

Figures

Pictures 1: Drawn by Dr. Sophie G. Elschner for the article.

Pictures 2: Drawn by Dr. Sophie G. Elschner for the article.

Pictures 3: Drawn by Dr. Sophie G. Elschner for the article.

Pictures 4: Drawn by Dr. Sophie G. Elschner for the article.