Justice seems not to be for all: Exploring the scope of justice

The idea that “justice is for everyone” seems to be over. A justice perception can have unfair consequences for those who are perceived not to be included within the boundaries of fairness. This is what the scope of justice is all about: who is within and who is outside of the “justice boundaries”. This paper intends to clarify the concept and explain how social psychologists work with it in real-life contexts. We argue that the scope of justice is a key concept that helps us to understand a broad range of intergroup conflicts, besides being an understudied phenomenon that motivates a variety of justice-related issues such as deservingness, animal rights, discrimination and environmental conflict. We also discuss and review the relevant literature concerning the psychological and social functions of the scope of justice, highlighting its possible antecedents and consequences. Finally, we outline the current applied research into the role played by processes used to legitimize damaging behaviors against people who are perceived to be outside of the scope of justice. In light of this concept, the “justice is for everyone” maxim should probably be changed to “justice is for those who are not excluded from our boundaries of fairness”.

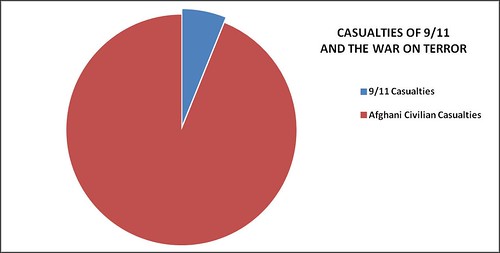

Ten years after 9/11, we witnessed the sympathy of (almost) the whole world for the victims of the attack on the World Trade Center (WTC) in New York. In 2011, the world watched live coverage of the tribute to the 2974 individuals who were killed at Ground Zero. During the tribute the name of each victim was remembered and announced by his or her relatives as a way of recognizing the value of each victim as a unique individual worthy of human appreciation. At the same time, we can easily find in human-rights reports the number of civilian casualties caused in the anti-terrorism war waged by the USA in Afghanistan. Although this number may sometimes be inflated, there appear to be around 40,000 people, including thousands of innocent children, who have been killed in Afghanistan since the beginning of the war.

Although the number of WTC casualties has been compared with the number of Afghan civilian casualties, it can easily be seen that the tributes and sympathy accorded to each group have not been the same. If human life is considered to be so important, and if it has the same value for everyone, then the sympathy felt for the casualties in Afghanistan should be the same or even greater than the sympathy felt for the WTC victims. Why is it then that people express different amounts of worry and sympathy for different groups (i.e., “my” group and “their” group)? Why is it that we do not feel the harm suffered by others as we feel the harm suffered by ourselves? For social psychologists, this is a question of justice concerns.

We often make decisions about justice-related issues in our daily lives. Every day we have to define (at least in our minds) whom it is important to care about and whom it is not. Who deserves our attention and who does not count? Usually, we care about and try to protect what we feel to be our group. In social psychology, this group is referred to as the

ingroup, i.e., a

social group to which an individual feels that he or she belongs. Similarly, “their group” is referred to as the

outgroup, i.e., those

social groups from which an individual feels the need to distinguish him or herself, which can be achieved through expressing contempt, opposition, or a

desire to compete. When we talk about group comparison, the

ingroup and the

outgroup are salient for those involved, and we often apply this differentiation between groups to justice-related issues.

We often make decisions about justice-related issues in our daily lives. Every day we have to define (at least in our minds) whom it is important to care about and whom it is not. Who deserves our attention and who does not count? Usually, we care about and try to protect what we feel to be our group. In social psychology, this group is referred to as the

ingroup, i.e., a

social group to which an individual feels that he or she belongs. Similarly, “their group” is referred to as the

outgroup, i.e., those

social groups from which an individual feels the need to distinguish him or herself, which can be achieved through expressing contempt, opposition, or a

desire to compete. When we talk about group comparison, the

ingroup and the

outgroup are salient for those involved, and we often apply this differentiation between groups to justice-related issues.

In this paper, we analyze an important process that affects the way that social judgments and decisions are made in relation to justice-related issues: the scope of justice. It is important to be familiar with this concept in order to understand how people morally justify their (good or bad) behavior and how people endorse the behavior of others in everyday life.