The price is right: how to get the best possible outcome in price negotiations

Editorial Assistant: Elena Benini.

Note: An earlier version of this article has been published in the German version of In-Mind.

Not every negotiation offers the possibility for win-win agreements. In simple price negotiations, one party’s loss implies an equal gain for the other party. This article outlines tactics and strategies from negotiation psychology that help you achieve the best outcome for yourself in such situations.

Many negotiations offer potential agreements through which all parties can win [1]. However, in some negotiations, a win-win solution is not possible. This is especially true for one-shot negotiations involving only one issue, such as price negotiations. Whether it's on eBay, purchasing an antique, or buying a piece of land: pure price negotiations are zero-sum games where one party gains what the other loses. In this article, we will show how to get the best possible outcome for oneself in such negotiations. Figure 1. What methods does negotiation psychology offer you?

Figure 1. What methods does negotiation psychology offer you?

Negotiating Means Giving and Taking

Have you ever had a negotiation where your first proposal was accepted immediately? If so, how satisfied were you with that negotiation outcome? Negotiation research suggests that in such situations, one is often dissatisfied because it creates the impression that one could have obtained even more [2]. However, the other extreme—where the other negotiating party stubbornly insists on their position—also does not lead to success or satisfaction for either party. The reason for this lies in the principle of reciprocity [3]. This fundamental psychological tendency refers to the need to respond in kind to other people’s positive or negative actions. If one negotiating party becomes obstinate, the other party will also become obstinate, leading to a negotiation impasse. As is often the case, the path to success in a negotiation lies between these two extremes, that is exchanging mutual concessions throughout the negotiation process. A concession is a change in one's own position towards the position of the other negotiating party. By making a concession, one leverages the principle of reciprocity, as this creates the need for the other party to reciprocate your concession. Successful negotiations thus consist of a give-and-take: both sides move closer to each other through concessions until they arrive at a price with which both are satisfied—or at least one that both can live with [1]. However, this does not mean that both parties must make equal-sized or equal-numbered steps toward each other.

Two Basic Concession Strategies

There are essentially two concession strategies in negotiations: the hard line and the soft line [4]. A hard line is characterized by (1) a negotiating party entering the negotiation with an extreme proposal, (2) making few concessions and (3) generally small incremental concessions, and (4) especially at the beginning of a negotiation, not deviating much from their position. In contrast, a soft line is characterized by (1) a moderate opening proposal and (2) more and (3) generally larger concessions, with (4) a greater willingness to accommodate at the beginning of a negotiation. Which of these strategies is more effective? That depends on the type of negotiation outcome: the negotiating party adopting a harder stance obtains better economic negotiation outcomes (e.g., a better price). However, this also increases the risk of a negotiation impasse [5]. Similarly, it worsens the so-called socio-emotional negotiation outcomes: compared to a negotiating counterpart who adopts a softer stance, a tough negotiating party is rated more negatively by the other party [4], which can strain parties’ relationship and future interactions. Therefore, experienced negotiators weigh which type of negotiation outcomes is more important and align their concession strategy accordingly.

The Limits of the Parties Determine the Zone of Possible Agreements

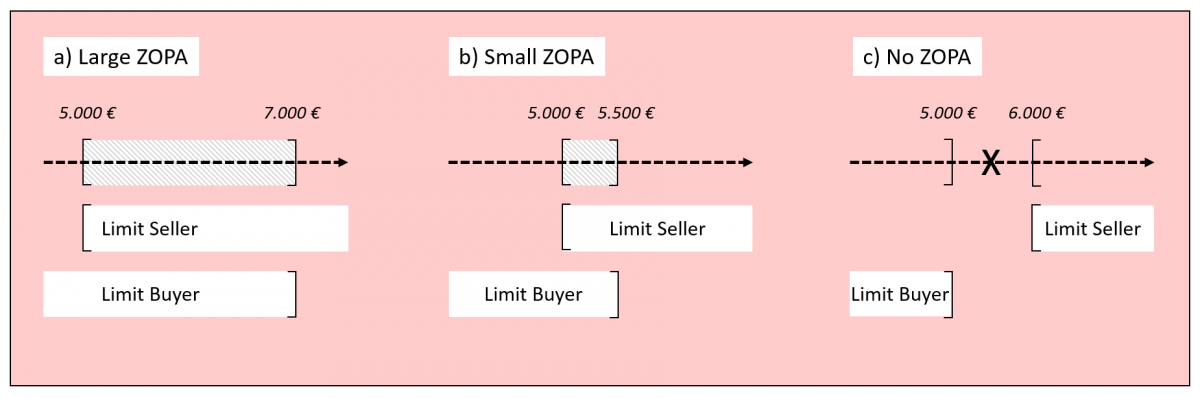

The extent to which a negotiating party can influence the economic negotiation outcomes in their favour depends on the limit of the other party. A limit is a threshold that the respective negotiating party cannot or does not want to exceed. Limits can be determined by given circumstances (e.g., the available budget) or can be arbitrarily set. A negotiation agreement should allow both parties to adhere to their limits. If one party gives more than they want or can, the agreement will lack

significant value to that party. The limits of the parties thus define the zone of possible agreements (ZOPA) [1]: the greater the overlap between the amount a buyer is willing to pay at maximum and the amount a seller wants to achieve at minimum, the larger the ZOPA. Therefore, to achieve the best outcome in a negotiation, you must push your counterpart as close as possible to their limit—while staying as far away as possible from your own [6]. Figure 2. The Zone of Possible Agreements in Negotiations

Figure 2. The Zone of Possible Agreements in Negotiations

The above description indicates that information about the other party's limit is immensely valuable, since it makes it easier to reach an agreement that is close to that limit [1]. Therefore, it is crucial to try to find out the other party's limit, or at least estimate it, before a negotiation begins. For example, suppose a negotiation about a used car. If the buyer knew that the seller had to cover a loan payment and would therefore accept a lower sale price, they could use this to their advantage. Conversely, one should not disclose one’s limit, as one would then grant a negotiation advantage to the other party. However, there are two exceptions to this rule [1]: First, when after a time-consuming negotiation process no substantial concession has been received from the other side, and one is considering withdrawing from the negotiation. In such a case, revealing one's limit can be a last resort to reach an agreement. The second exception is explained in the following, in connection with the best alternative to a negotiated agreement.

Negotiations Are Rarely Without Alternatives

The limit of a negotiating party can also depend on their best alternative to a negotiated agreement at the negotiation table. The best alternative is the outcome that occurs if no agreement is reached [7]. Ideally, there is an attractive alternative in a negotiation to fall back on if the negotiation fails. In the case of a used car negotiation, this could be a signed purchase contract with another dealer. Having an attractive alternative has enormous psychological benefits: one approaches the negotiation more optimistically, acts more proactively, negotiates harder, and is ultimately more successful [8].

Especially when the alternative is weak, it is crucial to try to improve it before a negotiation [1].

A similar situation pertains to the second exception mentioned above, where revealing one’s limit may make sense. If a very attractive deal is available, such as a

binding offer at favourable conditions, disclosing this to another negotiating partner at the beginning of the negotiation allows them to make an even better offer. If they do not, the alternative deal can be accepted without going through the second negotiation [1]. Figure 3. Price negotiations, such as those for a used car, rarely allow for win-win agreements. Nevertheless, you can still achieve the best possible outcome for yourself.

Figure 3. Price negotiations, such as those for a used car, rarely allow for win-win agreements. Nevertheless, you can still achieve the best possible outcome for yourself.

Ambitious Goals Lead to Better Negotiation Outcomes

In addition to limits, each negotiating party should set their goal before a negotiation. A negotiation goal is a specific value (e.g., a price) that they deem ambitious but achievable. For example, if the buyer estimates the value of a certain used car to be around €6,000, their goal price might be €5,500. Setting an ambitious, specific goal is an important step in maximizing outcomes in negotiations. At the same time, it is important to hold onto one’s goal as long as possible and not be (too hastily) swayed by the actions of the other party. This way, one negotiates harder and avoids (unnecessary) concessions [9].

The Opening Proposal Significantly Influences the Negotiation Outcome

Whoever makes the first proposal in a negotiation usually has a strategic advantage. If one has a rough idea of the value of an object and thus where the ZOPA might lie, an ambitious opening proposal is a highly effective means to maximize one's outcome. The reason for this lies in the anchoring bias: When making decisions, there is a tendency for people to rely too heavily on the first piece of information they receive (the anchor), which can bias their subsequent judgments and choices [10]. In negotiations, just as an anchor holds a ship in a specific place in the water, the first negotiation proposal exerts a strong pull, causing the other party to unconsciously align their counterproposal with this proposal [11]. As parties move closer to each other through mutual concessions during a negotiation, and this process begins with the opening proposals, throwing a "heavy anchor" in the form of an ambitious opening proposal influences the negotiation from the outset in favour of the one who threw the anchor. To use this anchoring technique in a negotiation effectively, the first proposal should be ambitious but not too extreme, as otherwise the other party may perceive the proposal as insulting and withdraw from the negotiation [12]. For instance, if the buyer suspects that the used car has a value of around €6,000 and has set a

goal of €5,500, they might make an opening proposal of €5,000. However, they should not start the negotiation at €2,000.

There are several ways to further enhance the impact of the first proposal, regardless of its extremity: precise anchors (e.g., €4,985) are more effective than round anchors (e.g., €5,000) because they appear more plausible and less arbitrary [13]. Also effective are so-called phantom anchors, where the actual first proposal is combined with an even more extreme proposal that is then immediately withdrawn (e.g., buyer: “I was actually going to suggest €4,000 for the car, but I offer you €5,000.”). This way, the recipient of the proposal is led to believe that a concession has been made, which in turn increases their willingness to accommodate the sender of the proposal [14]. Sometimes, one might be surprised by the anchor from the other party and thereby inhibited from making their own opening proposal. In such cases, countering with one’s own, prepared anchor avoids giving the counterpart a strategic advantage [1].

Substantial Arguments Make Negotiation Proposals More Convincing

Not only is the content of the proposals one makes in negotiations important for their success but also how they are presented. As a general rule, negotiation proposals are more convincing when supported by fact-based arguments [6]. For example, the buyer in our example could justify their opening proposal of €5,000 by pointing out that the used car has several visible defects (if this is true). Weak, easily refutable arguments, on the other hand, reduce the likelihood that one’s proposal will be accepted and should therefore be avoided.

Offers Are More Effective Than Demands

In addition to the substantive backing through convincing arguments, one can also subtly increase the effectiveness of their proposals through so-called procedural framing. Negotiating parties are more willing to make concessions when their attention is focused on what they will gain from an agreement (Gain Frame) rather than on what they will lose (Loss Frame). The reason for this lies in the psychological principle of loss aversion [15]: People are more willing to accept a reduction in their gains than an equally sized increase in their losses. If a negotiating party has a gain frame, a concession to the other party means “only” a reduction in their gains. In contrast, when being in a loss frame, a concession means a painful increase in one’s own loss. This psychological experience of gains and losses by the negotiating partner can be systematically influenced by the way proposals are formulated. A counterpart might more easily adopt a gain frame and thereby be more willing to concede, if (a) they receive offers (instead of requests) and (b) they first know what they will receive [15]. For instance, a buyer could formulate a negotiation proposal as follows: “I offer you €5,000 for the used car.” This proposal focuses on the money the seller receives upon agreement (i.e., their gain). In contrast, requests about the used car move the focus on what the seller loses upon agreement, and therefore should be avoided (“I request the used car for €5,000”). Crucially, both formulations objectively contain the same information, namely a price proposal of €5,000. Framing effects thus operate on a psychological level and are therefore applicable regardless of the content of a proposal.

Conclusion

In negotiations with a zero-sum character, where one party gains what the other loses, there are numerous ways to improve one’s outcome. This starts in the preparation phase by setting goals and limits as well as seeking a strong alternative. However, throughout the negotiation process, one’s outcome can be improved, for example, through the design of the opening proposal or systematic concessions. Negotiation psychology offers a rich toolbox to help negotiators achieve the best possible outcome for themselves.

Bibliography

[1] L. L. Thompson, The Mind and Heart of the Negotiator, 6th ed. Pearson, 2015.

[2] A. D. Galinsky, V. L. Seiden, P. H. Kim, and V. H. Medvec, "The dissatisfaction of having your first offer accepted: The role of

counterfactual thinking in negotiations," Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 271–283, 2002. doi: 10.1177/0146167202282012.

[3] L. R. Weingart, L. L. Thompson, M. H. Bazerman, and J. S. Carroll, "Tactical behavior and negotiation outcomes," International Journal of Conflict Management, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 7–31, 1990. doi: 10.1108/eb022670.

[4] J. Hüffmeier, P. A. Freund, A. Zerres, K. Backhaus, and G. Hertel, "Being tough or being nice? A

meta-analysis on the impact of hard- and softline strategies in distributive negotiations," Journal of Management, vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 866–892, 2014. doi: 10.1177/0149206311423788.

[5] W. C. Hamner, "Effects of bargaining strategy and pressure to reach agreement in a stalemated negotiation," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 458–467, 1974. doi: 10.1037/h0037026.

[6] D. Malhotra and M. H. Bazerman, Negotiation Genius: How to Overcome Obstacles and Achieve Brilliant Results at the Bargaining Table and Beyond. Bantam, 2008.

[7] R. Fisher and W. Ury, Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981.

[8] A. D. Galinsky, M. Schaerer, and J. Magee, "The four horsemen of

power at the bargaining table," Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, vol. 32, no. 4, p. 606, 2017. doi: 10.1108/JBIM-10-2016-0251.

[9] L. Thompson, "The impact of minimum goals and aspirations on judgments of success in negotiations," Group Decision and Negotiation, vol. 4, no. 6, pp. 513–524, 1995. doi: 10.1007/BF01409713.

[10] D. Kahneman and A. Tversky, "Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk," Econometrica, vol. 47, pp. 263–291, 1979.

[11] A. D. Galinsky and T. Mussweiler, "First offers as anchors: The role of perspective-taking and negotiator focus," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 81, pp. 657–669, 2001. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.81.4.657.

[12] M. Schweinsberg, G. Ku, C. S. Wang, and M. M. Pillutla, "Starting high and ending with nothing: The role of anchors and

power in negotiations," Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, vol. 48, pp. 226–231, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2011.07.005.

[13] D. D. Loschelder, J. Stuppi, and R. Trötschel, "€ 14,875?!: Precision boosts the anchoring potency of first offers," Social Psychological and Personality Science, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 11–16, 2014. doi: 10.1177/1948550613499942.

[14] N. Bhatia and B. C. Gunia, "I was going to offer $10,000 but…: The effects of phantom anchors on negotiations," Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, vol. 148, pp. 70–86, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2018.06.003.

[15] R. Trötschel, D. D. Loschelder, B. P. Höhne, and J. M. Majer, "Procedural frames in negotiations: How offering my resources versus requesting yours impacts

perception, behavior, and outcomes," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 108, pp. 417–435, 2015. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000009.

Figures sources

Figure 1 source: https://www.pexels.com/de-de/foto/stadt-mann-menschen-frau-4963437/

Figure 2 source: Self-illustration

Figure 3 source: https://www.pexels.com/de-de/foto/frau-auto-fahrzeug-stehen-7144185/