The Force is Too Strong with This One? Sexism, Star Wars, and Female Heroes

t-reys-lightsaber-extra from inverse.com via Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, Lucasfilm Animation (http://media.vanityfair.com/photos/5925ab0c7b959f02077a7479/16:9/pass/t-reys-lightsaber-extra.jpg?mbid=social_retweet), cc (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/)

t-reys-lightsaber-extra from inverse.com via Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, Lucasfilm Animation (http://media.vanityfair.com/photos/5925ab0c7b959f02077a7479/16:9/pass/t-reys-lightsaber-extra.jpg?mbid=social_retweet), cc (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/)

The newest installment of the Star Wars saga, The Last Jedi, was released last month. Despite critical success, the film has been met with a polarized audience reaction online. Although likely not the primary reason for polarization, some of the negative reaction can be attributed to the perceived progressive, feminist political message of the main characters[1]: The primary protagonist, Rey, is a woman; the two most prominent White men, Kylo Ren and General Hux, are villains. Behind the scenes, women have powerful roles in the franchise, as president of Lucasfilm (Kathleen Kennedy) and as the head of the writers group (Kiri Hart); the New York Times recently ran a story about these women who "run the Star Wars universe"[2]. An alt-right group, unhappy with this, took credit for flooding Rotten Tomatoes with negative reviews of The Last Jedi.[3]

Two years ago, we noticed a similar reaction to The Force Awakens and thought that some negative reactions to Rey as a character were partially motivated by sexism. Rey begins the movie as an orphaned scavenger, making her way on an isolated desert planet by finding pieces of downed spaceships and selling them for dehydrated food. After coming across a droid carrying part of a map to the legendary Luke Skywalker—hero of the original trilogy—she is swept up into the battle between the light and dark side of the Force (an energy field that connects all living things in the Star Wars Universe).

As any hero in an epic saga, Rey is remarkably powerful. She quickly learns how to use the Force; not only does she successfully resist Kylo Ren—the film’s primary villain who is trained in the Force—when he tries to read her mind, she counters the attempt and looks into his mind. Rey defeats Kylo Ren in hand-to-hand combat using the Jedi’s trademark weapon, the lightsaber, despite never having wielded one before.

Some critics have called Rey’s competence and mastery of the Force into question, doubting that an untrained and seemingly ordinary person could possess such powers. Others have suggested, however, that these criticisms reflect a sexist response to seeing a strong leading woman in a Hollywood blockbuster[4]. Are perceptions of Rey’s competence in the Force driven completely by genuine concerns about the film’s plot, or can they also be traced to sexist attitudes?

Women have been underrepresented in film throughout the history of American cinema, both on-[5] and off-screen[6]. When women do appear in a films their characters tend to adhere to common stereotypes (e.g., weak, subordinate) and archetypes (e.g., "damsel in distress")[7]. Casting the main protagonist of The Force Awakens as a female was, in part, to subvert these stereotypical representations of women in film[8]. Rey is thus a symbolic denial of the traditional roles and stereotypes of women in film and society; we predicted that certain sexists would dislike this denial.

Sexism isn’t characterized only by antipathy and prejudice against women[9]. Ambivalent sexism[10] is a model of sexism that appreciates this nuance by including two dimensions of sexism: hostile and benevolent sexism. Hostile sexism includes negative feelings toward women and beliefs that gender relations are adversarial and competitive (e.g., believing feminists are trying to control men). Benevolent sexism includes positive feelings toward women that exist alongside beliefs that reflect traditional gender stereotypes. Benevolent sexists view women as weak and pure, and they feel women should be protected and adored.

Hostile sexism predicts negative stereotypes about women, while benevolent sexism predicts positive stereotypes about women[11]. Hostile sexism predicts negative evaluations of nontraditional women (e.g., businesswomen, feminists), while benevolent sexism predicts positive evaluations of traditional women (e.g., homemakers), and these nontraditional women are perceived as competent, but not warm[12].

How will benevolent and hostile sexism influence attitudes about Rey? She is the lead protagonist of The Force Awakens, is both physically and mentally competent with the Force, and does not adhere to the traditional gender stereotypes; thus, we predicted that it would be hostile—but not benevolent—sexism that would predict unfavorable attitudes towards Rey.

Our Study

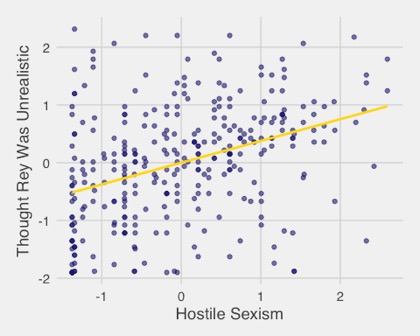

At the beginning of 2016, we gave a survey to 322 people on Amazon's Mechanical Turk who had seen Star Wars: The Force Awakens. We asked these participants about how realistic they thought Rey was, given what they know about the Star Wars Universe (e.g., "Rey is unrealistically good at everything: She can fix machines, pilot a ship well, learns the Force quickly, and is naturally good with a lightsaber"). Participants also filled out a scale that measured hostile (e.g., "Many women are actually seeking special favors, such as hiring policies that favor them over men, under the guise of asking for 'equality'") and benevolent (e.g., "Women should be cherished and protected by men") sexism. Lastly, they told us how much of a fan they were of Star Wars, how much they identify as conservative, and their gender (coded as male or not male), race (coded as White or not White), and age.

After taking into account everything else we measured (e.g., conservatism, gender, etc.), hostile sexism—but not benevolent sexism—predicted beliefs that Rey was unrealistic: The more hostile sexist attitudes someone had, the more unrealistic they thought Rey was. Interestingly, gender did not matter much. After taking into account the role of sexist attitudes, men and women did not differ in their attitudes toward Rey.

The release of The Force Awakens (much like the recent The Last Jedi) was a massive cultural event, and the movie was a hit with audiences and critics. Yet the main character, a woman named Rey, was criticized as being unrealistic due to her extremely high level of competence—a trait that many heroes in fantasy, action, science fiction, and superhero films share.

We empirically tested the contention that this incredulity around Rey was, at least in part, sexist. This supports Daisy Ridley—who plays Rey—saying that some of the criticism of her character is sexist[13]. When compared to other social, political, and demographic variables we measured, including the extent to which participants’ called themselves Star Wars fans, hostile sexism was the strongest predictor of believing that Rey's competencies made her "unrealistic."

These data show how sexism can shape discourse surrounding large cultural events in a way that can mask prejudice. Because explicitly prejudiced statements are socially unacceptable in contemporary North American culture, negative feelings toward disliked groups must be expressed in rearticulated, coded forms.

The conversation about Rey may seem as a superficial, pop-cultural bickering among fans of the Star Wars franchise, but these data support the idea that it is fueled in part by sexism. In a society that doesn’t tolerate outright bigotry, it is crucial that we also examine the sexist undercurrents in ostensibly gender-neutral conversations.

Note: For details about analysis and data see https://github.com/markhwhiteii/blog/blob/master/rey/sw_blog_details.pdf

References

[1] VanDerWerff, T. (2017, December 19). The “backlash” against The Last Jedi, explained. Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/culture/2017/12/18/16791844/star-wars-last-jedi-backlash-controversy

[2] Holt, N. (2017, December 22). The women who run the 'Star Wars' universe. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/22/movies/star-wars-last-jedi-women-run-universe.html

[3] Sharf, Z. (2017, December 21). Alt-right group takes credit for ‘The Last Jedi’ backlash, bashes ‘Star Wars’ for including more women. Retrieved from http://www.indiewire.com/2017/12/star-wars-last-jedi-backlash-alt-right-female-characters-1201910095/

[4] Anders, C. J. (2015, December 21). Please stop spreading this nonsense that Rey from Star Wars is a “Mary Sue.” Retrieved from http://io9.gizmodo.com/please-stop-spreading-this-nonsense-that-rey-from-star-1749134275

[5] Eschholz, S., Bufkin, J., & Long, J. (2002). Symbolic reality bites: Women and racial/ethnic minorities in modern film. Sociological Spectrum, 22(3), 299-334.

[6] Lauzen, M. M. (2012). Where are the film directors (who happen to be women)? Quarterly Review of Film and Video, 29(4), 310-319.

[7] Benshoff, H. M., & Griffin, S. (2004). America on film: Representing race, class, gender, and sexuality at the movies. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

[8] Plattner, S. (2015, December 18). Can an unknown named Daisey Ridley take over the ‘Star Wars’ empire? Retrieved from http://www.elle.com/culture/celebrities/interviews/a31408/daisy-ridley-elle-december-2015-cover-story/

[9] Jackman, M. R. (1994). The velvet glove: Paternalism and conflict in gender, class, and race relations. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

[10] Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(3), 491-512.

[11] Glick, P., Fiske, S. T., Mladinic, A., Saiz, J. L., Abrams, D., Masser, B., …López, W. L. (2000). Beyond prejudice as simply antipathy: Hostile and benevolent sexism across cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(5), 763-775.

[12] Fiske, S. T., Xu, J., Cuddy, A. C., & Glick, P. (1999). (Dis)respecting versus (dis)liking: Status and interdependence predict ambivalent stereotypes of competence and warmth. Journal of Social Issues, 55(3), 473-489.

[13] Jusino, T. (2017, December 21). We Need to Talk About the Backlash Against Rey (Again), and Why She’s Awesome. https://www.themarysue.com/lets-talk-about-rey-and-rey-backlash/