Sex differences in the perception of sexual arousal

“Men are from mars, women are from Venus” [1] this saying often appears as common knowledge. Particularly the sexuality of men and women is often considered to be fundamentally different. Research, however, demonstrates that the physiological processes underlying sexual arousal in men and women are surprisingly similar [2]. This finding is in marked contrast to men’s and women’s reports of subjectively experienced sexual arousal. When asked about their subjective sexual arousal to erotic stimuli, men consistently report higher sexual arousal than women, even though their measured physical reactions are fairly similar [3]. How is it possible that men and women differ so fundamentally in their subjective arousal when their physiological arousal is so similar?

Sigmund Freud [4] is quoted as having said: “The great question that has never been answered, and which I have not yet been able to answer, despite my thirty years of research into the feminine soul, is: what does a woman want?” Popular opinion shares that notion: While men supposedly are constantly interested in sex, women’s interest is perceived as unpredictable. This perception is also reflected in the differential interest in hardcore pornography. While there is a market out there for pornography specifically targeting women, men consume more pornography, and they more often consume it more excessively [5]. The question arises: are men and women really that different when it comes to their sexual arousal as it is portrayed by the public? Let’s take a closer look.

Multiple studies have shown that the genital-physiological reaction of men and women in response to visual sexual stimuli, i.e., pornography, is very similar. For example, in research where a thermal imaging camera is pointed at the genitals of participants while they are watching pornographic material of a man and a woman engaging in coitus, maximal arousal is reached after approximately 10 minutes (measured in temperature differences), independent of participants’ sex [3].

Schematic representation of a thermal image of female genitalia

Source: A. Baranowski

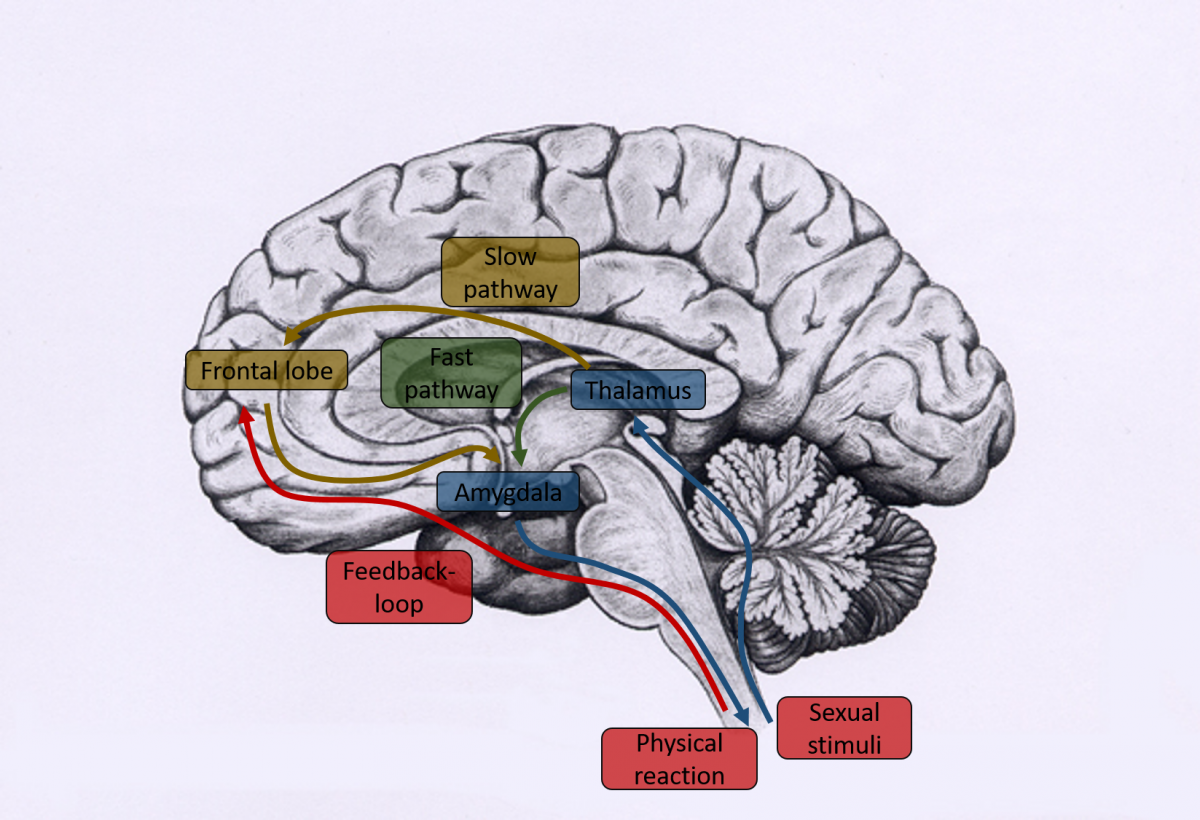

Similar results are found in the neurobiology of sexual arousal. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging ( fMRI), the neuronal activity in response to pornographic material looks fairly similar in the brains of men and women [2]. Neither the relevant regions nor their amount of activity differs considerably. In the literature, we find that sexual stimuli in both sexes are processed in two ways, called slow cognitive and fast automated [6]. In the slow, cognitive pathway, sexual stimuli first pass through the thalamus (due to its filter functions also called “gate to consciousness”), where they are preprocessed. Through cognitive (frontal lobe) and experience-based ( hippocampus) evaluation they are then categorized as sexual, which leads to top-down modulation of sensory processes. Therefore, the processing of sexual stimuli is influenced by learning experiences (e.g., previous experiences, knowledge, expectations, context), and volition (e.g., decisions, motivation), and not exclusively by the present physical characteristics of the stimuli. In the second, fast pathway, stimuli are evaluated due to their emotional valence ( amygdala), which leads to a reaction that is independent of consciousness. This can result in a timely delayed genital physiological reaction (erection and lubrication, see also [7]). Here, cognitive processes are not relevant. This means that there are probably two systems, which to an extent, are independent from one another: a cognitive system, which assesses a given situation using previous experiences and knowledge, and a fast system, which reacts autonomously to sexual stimuli with physical changes [8]. Both pathways interact with each other, similar to the processing of other emotions.

Neuronal pathway of sexual arousal

Source: A. Baranowski

For explicitly reported sexual arousal, we frequently observe a different scenario: Men generally judge images and film clips of sex scenes as more arousing compared to women [9]. Additionally, heterosexual men compared to heterosexual women, report clips with an attractive main actress and the opportunity to observe her, more arousing. Women, in contrast, rate clips that were produced or chosen by women, and in which they can imagine themselves participating, as the most stimulating [9], [10]. Women also show less of a same- sex bias, such that they are less category-specific and are equally aroused by explicit content that shows women or men, while men are significantly more aroused to the sex they are attracted to [11]. Surprisingly, in men, the measured genital reaction is mostly in concordance with the reported arousal, while this is not the case for women [12]. Simply put, men are genitally aroused by what they report to be a turn on. However, for women, the reported arousal and genitally recorded reaction are only weakly correlated; genital reaction does not translate as strongly to reported experienced arousal.

In one study, different sex scenes were shown to men and women, while their genital reaction was recorded [13]. Presented scenes included heterosexual sex, homosexual sex, a man masturbating, a woman masturbating, a naked man walking on a beach, a naked woman exercising, and mating bonobos (pygmy chimpanzees). After seeing these scenes, participants were asked to rate their experienced sexual arousal. Men showed the expected reaction pattern: heterosexual men were turned on by women and homosexual men by men. The reported arousal was mostly in concordance with the physiologically recorded reaction of the penis. Female participants also reported being mostly aroused by sexual interaction of their preferred sex. None of the women reported being turned on by ape sex. However, the genital physiological reaction showed a different pattern: Women were aroused by all sexual interactions, independent of their sexual orientation. Even two bonobos copulating led to a rise in blood flow and lubrication in the vagina. This poses the question: How is it possible that women are aroused by viewing sex acts, but do not consciously report experiencing it?

Two bonobos mating

Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/80/Bonobo_sexual_behavi...

To understand this “split” between physiological and experienced arousal, several explanations have been proposed. The authors of the bonobo-study themselves argue that women were constantly presented with the danger of sexual violence in prehistoric times [13]. Women who reacted with lubrication to any sexual encounter, independent of consent, were less likely to experience genital injuries. This would have led to fewer problems like infections and, as a consequence, lower mortality in women who showed an unspecific genital reaction pattern, so that such a pattern could evolutionary prevail. This means women are genitally aroused by any presentation of sexuality, even if they don’t experience sexual desire.

Many authors also assume that men have a predisposition to motivationally react stronger to sexual stimuli than women (e.g., [14]). The evolutionary costs of rejected advances for men is significantly lower than of a missed mating opportunity. The former only leads to minor social repercussions while the later leads to a missed opportunity to pass on one’s genes. Because evolutionary strategies securing survival and reproduction prevail, high sexual motivation for men is comprehensible [14]. Women carry the higher cost of copulation such that mating can lead to pregnancy and therefore to a “burden” of at least nine months. Hence, a selective strategy is evolutionarily advantageous. This means that for women, even when the evolutionary highly conserved mechanism of sexual arousal is activated by an attractive potential sexual partner, it makes sense to not immediately give in to the sexual impulse, but critically question their own action [14]. With this in mind, the decoupling of physiological and subjective reaction is evolutionarily advantageous for women. This reduces the motivational component of the physiological reaction and allows for a more flexible mating strategy.

Besides evolutionary reasons, further differences lie in the anatomy of the sexes [15]. Male genitalia are externally located and changes are registered almost immediately. More blood circulation of the penis leads to erection, which is felt through contact with clothing distinctly, and, depending on the context, also seen clearly. The association of experienced arousal and genital-physiological changes are, through this mechanism, reinforced with each erection. Changes in the vagina and clitoris are, in contrast, mostly internal and are not felt, let alone seen, to that extent. This means that the association between genital-physiological and experienced arousal is substantially weaker because not every instance of a physiological reaction is immediately felt and interpreted [16].

Additionally, men are culturally emboldened to name and express things they find sexually arousing [17]. They are encouraged to experiment with (heteronormative) sexuality while women, in contrast, often get mixed feedback. They are encouraged to present themselves as “sexy” and at the same time are attributed as “easy to get” when they act accordingly. This double standard can lead to a suppression of sexual arousal that is experienced as positive on an individual level but sanctioned at a societal level [18]. This discrepancy of societal expectations and inner experiences can lead to such a feeling of uncertainty, and as a result, women stop trusting their own perceptions of their body. The consequence can be a discord between genital-physiological and experienced sexual arousal. Additionally, this can lead to distorted answers about the state of arousal of female participants in experiments due to societal expectations, because sanctions in the form of negative evaluation by the investigator are feared [19].

In contrast to what many people think, the concordance between measurements for men also does not reach 100% and can vary strongly depending on the situation. A meta-analysis, which analyzed the relationship between physiological and subjective arousal in 132 studies, found a concordance of 44% for men and 7% for women [12]. These results support the claim that genital-physiological and subjectively experienced arousal are both managed by two different systems, which to a certain extent are independent of one another.

The sex differences in concordance between objective and subjective arousal can best be summarized as follows: The physiological arousal process, which likely evolved to maximize reproductive success, appears to be quite similar in men and women. However, men react motivationally stronger to sexual stimuli due to the evolutionary low “costs”. Women, in contrast, react to sexual stimuli with lubrication, to protect their inner sexual organs, independent of their experienced arousal. Due to the specific anatomy and social influences, men learn to better align their experienced sexual arousal with their physiological reaction. Women, on the other hand, learn early on, not to trust their bodily reactions, as they are often in contrast to social expectations.

Further studies should focus on the reported arousal and its interaction with physical arousal. While we have a good understanding of the anatomical and physiological processes that accompany arousal (see e.g., Sildenafil), the experience of desire and pleasure and its involved components, as well as how it translates to physiological arousal, is still insufficiently explained. A better understanding of these processes would allow for the development of new interventions for sexual dysfunctions, particularly for heightened (hypersexuality) and reduced (hyposexuality) sexual desire.

References

- Gray, J. (1992). Men are from Mars, women are from Venus : a practical guide for improving communication and getting what you want in your relationships. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

- Wehrum, S., Klucken, T., Kagerer, S., Walter, B., Hermann, A., Vaitl, D., & Stark, R. (2013). Gender commonalities and differences in the neural processing of visual sexual stimuli. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10(5), 1328–1342. Doi: 10.1111/jsm.12096

- Kukkonen, T. M., Binik, Y. M., Amsel, R., & Carrier, S. (2007). Thermography as a physiological measure of sexual arousal in both men and women. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 4(1), 93–105. Doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00399.x

- Elms, A. C. (2001). Apocryphal Freud: Sigmund Freud’s most famous “quotations” and their actual sources. The Annual of Psychoanalysis, 29, 83–104.

- Carroll, J. S., Padilla-Walker, L. M., Nelson, L. J., Olson, C. D., McNamara Barry, C., & Madsen, S. D. (2008). Generation XXX: Pornography acceptance and use among emerging adults. Journal of Adolescent Research, 23(1), 6–30. Doi: 10.1177/0743558407306348

- LeDoux, J. E. (2000). Emotion circuits in the brain. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 23(1), 155–184. Doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.155

- Stoléru, S., Fonteille, V., Cornélis, C., Joyal, C., & Moulier, V. (2012). Functional neuroimaging studies of sexual arousal and orgasm in healthy men and women: A review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 36(6), 1481–1509. Doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.03.006

- Janssen, E., Everaerd, W., Spiering, M., & Janssen, J. (2000). Automatic processes and the appraisal of sexual stimuli: Toward an information processing model of sexual arousal. Journal of Sex Research, 37(1), 8–23. Doi: 10.1080/00224490009552016

- Janssen, E., Carpenter, D., & Graham, C. A. (2003). Selecting films for sex research: gender differences in erotic film preference. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 32(3), 243–251.

- Laan, E., Everaerd, W., van Bellen, G., & Hanewald, G. (1994). Women’s sexual and emotional responses to male- and female-produced erotica. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 23(2), 153–169.

- Chivers, M. L., Rieger, G., Latty, E., & Bailey, J. M. (2004). A sex difference in the specificity of sexual arousal. Psychological Science, 15(11), 736–744. Doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00750.x

- Chivers, M. L., Seto, M. C., Lalumière, M. L., Laan, E., & Grimbos, T. (2010). Agreement of self-reported and genital measures of sexual arousal in men and women: A meta-analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(1), 5–56. Doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9556-9

- Chivers, M. L., Seto, M. C., & Blanchard, R. (2007). Gender and sexual orientation differences in sexual response to sexual activities versus gender of actors in sexual films. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(6), 1108–1121. Doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.6.1108

- Buss, D. M. (2015). Evolutionary psychology: The new science of the mind. (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Woodard, T. L., & Diamond, M. P. (2009). Physiologic measures of sexual function in women: a review. Fertility and Sterility, 92(1), 19–34. Doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.04.041

- Pennebaker, J. W., & Roberts, T.-A. (1992). Toward a his and hers theory of emotion: Gender differences in visceral perception. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 11(3), 199–212. Doi: 10.1521/jscp.1992.11.3.199

- Marks, M. J., Young, T. M., & Zaikman, Y. (2019). The sexual double standard in the real world: Evaluations of sexually active friends and acquaintances. Social Psychology, 50(2), 67–79. Doi: 10.1027/1864-9335/a000362

- Baranowski, A. M., & Hecht, H. (2015). Gender differences and similarities in receptivity to sexual invitations: Effects of location and risk perception. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(8), 2257–2265. Doi: 10.1007/s10508-015-0520-6

- Alexander, M. G., & Fisher, T. D. (2003). Truth and consequences: Using the bogus pipeline to examine sex differences in self‐reported sexuality. Journal of Sex Research, 40(1), 27–35. Doi: 10.1080/00224490309552164