“White and educated?” Toward a (more) diverse climate movement

Note: An earlier version of this article has been published in the German version of In-Mind.

Editorial Assistants: Elisabeth Höhne and Jana Dreston

Incidents like the one involving Ugandan activist Vanessa Nakate, who was cropped out of a group photo with other climate activists, are emblematic of the assumption that climate protection is primarily a concern of White people. In this article, we explore potential (social) psychological explanations for the lack of (perceived) diversity in climate activism, as well as approaches to increase diversity.

In early 2020, a photo of climate activists at the World Economic Forum in Davos circulated in the media, from which Vanessa Nakate, a Ugandan activist and the only BIPoC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) in the photo, had been cropped out. Other news outlets, while using an uncropped photo that included Vanessa Nakate, mistakenly identified her as Natasha Mwansa, a climate activist from Zambia. A series of similar incidents has since come to light, reigniting an ongoing debate about why climate protection is often perceived primarily as a concern of White people, and what barriers BIPoC face in their activism. Indeed, when looking at activists and initiatives in the Global North, one could have the impression that it is White people who are primarily involved in climate activism. Similarly, climate movements are dominated by educated individuals with middle-class backgrounds, whereas people with lower socioeconomic status are significantly underrepresented [1].

Image 1: BIPoC and people with lower socioeconomic status are underrepresented in the climate movement in countries within the Global North.

Image 1: BIPoC and people with lower socioeconomic status are underrepresented in the climate movement in countries within the Global North.

The article is divided into three parts. First, drawing on social psychological research, we outline various mechanisms that can explain the relatively low levels of diversity in climate activism, particularly the underrepresentation of BIPoC and individuals with lower socioeconomic status.1 Next, we analyze the issue of low diversity within the climate movement from a climate justice perspective. The final section focuses on various strategies that might help increase diversity in the climate movement.

Psychological Explanations for the Low Diversity in the Climate Movement

(Social) psychological research offers several explanations for why

BIPoC and people with lower

socioeconomic status are underrepresented in the climate movement. Here, we focus specifically on the role of

stereotypes, i.e., traits ascribed to

social groups and their members, as well as the role of experienced or anticipated

discrimination.

In Western societies, the

stereotype persists that

BIPoC and people with lower

socioeconomic status are less concerned about the environment and climate change than White, middle-class individuals. Media portrayals contribute to this

stereotype by excluding these groups from climate-related contexts, as seen in the opening example, or by associating them with environmentally harmful behaviors such as littering [2]. However, research has repeatedly shown that the assumption of lower concern about climate change and the environment is inaccurate. Findings suggest that in the U.S.,

BIPoC and individuals with lower

socioeconomic status report even higher levels of concern about climate change and the environment than White individuals and those with higher

socioeconomic status [3]. This constellation might affect the diversity of climate movements in several ways. First, the

stereotype that

BIPoC and those with lower

socioeconomic status care less about the environment may prevent members of these groups from being seen as potential actors in the climate movement, leading to fewer efforts to actively recruit them (e.g., in campaigns). Second, the

stereotype may cause

BIPoC and individuals with lower

socioeconomic status to perceive weaker

social norms within their own groups regarding concern for the environment and climate change. Perceived group norms, i.e., perceived rules about what attitudes and behaviors are prevalent and valued within a

social group, in turn, are an important motivator for climate-protective behavior [4]. Crucially, this

stereotype may not only be held by White, middle-class people;

BIPoC and people with lower

socioeconomic status may also share the

perception that concern for the environment is an issue of White, middle-class people, thus decreasing their motivation to join climate movements [3]. Third, the

stereotype may lead

BIPoC and individuals with lower

socioeconomic status to feel like outsiders within their own

ingroup. Research supports this, suggesting that

BIPoC and lower

socioeconomic status individuals perceive themselves as more concerned about the environment and climate change than they believe their

ingroup is in general [3]. The

stereotype can thus be seen as a shared misperception, where individuals wrongly assume that other group members do not share their personal concern for climate change. This might, in turn, lead

BIPoC and individuals with lower

socioeconomic status to avoid discussing climate-related topics out of fear of provoking (falsely assumed) negative reactions from other

ingroup members. Empirical evidence supports these processes: People who believed that the majority of their

ingroup did not share their concern about climate change were more likely to avoid discussing the topic with others from their

ingroup [5]. This self-reinforcing cycle might contribute to

BIPoC and people with lower

socioeconomic status failing to recognize other

ingroup members as potential climate activists, leaving a crucial collective potential within the climate movement untapped. Fourth, the

stereotype may also lead

BIPoC and people with lower

socioeconomic status to perceive themselves as atypical of the climate movement and, as a result, to fear being outsiders in activist circles.

Additionally, as the climate movement exists within a society affected by racism and classism, experienced or anticipated

discrimination (i.e., the negative treatment due to belonging to a negatively stereotyped group) within the climate movement is another potential factor contributing to the underrepresentation of

BIPoC and people with lower

socioeconomic status. To our knowledge, there are no empirical studies that address experiences of

discrimination within the climate movement, but there are a number of anecdotal reports and studies from related fields. For instance,

BIPoC students in sustainability studies report experiences of systemic racism (e.g., in the form of

discrimination) that contribute to feelings of isolation and exclusion [6]. Research on the consequences of everyday racism in organizations suggests that such experiences could lead

BIPoC to disengage [7]. Importantly,

discrimination does not have to occur within the climate movement itself:

Discrimination experienced in other areas of life or second-hand accounts of such experiences can also lead

BIPoC and people with lower

socioeconomic status to avoid climate organizations or groups dominated by White people and individuals with middle-class backgrounds.

The

stereotype that

BIPoC and people with lower

socioeconomic status are less concerned about the environment and climate change can therefore lead members of these groups to a) not being recognized and recruited as potential activists (“We don’t even need to ask them”), b) not perceiving concern for the environment as a relevant

ingroup norm (“That’s more their issue, not ours”), c)

feeling like lone actors within their

ingroup (“I’m the only one in my group who cares about this”), and d) perceiving themselves as outsiders in activist circles (“I don’t fit in here”). Together with experiences or fears of

discrimination within the climate movement, these processes may contribute to the underrepresentation of

BIPoC and people with lower

socioeconomic status in the climate movement.

Climate Justice and Low Diversity in the Climate Movement

– A Paradox

The underrepresentation of BIPoC and people with lower socioeconomic status in the climate movement is particularly concerning when we consider who is most vulnerable to, and disproportionately affected by, the negative impacts of climate change. Globally, it is primarily impoverished communities and BIPoC—those who are the least responsible for climate change—who suffer the most [8],[9]. For example, the Global North produces significantly more CO2 emissions than the Global South, yet countries in the Global South are disproportionately affected by climate change. Similarly, the richest 1% of people worldwide produce 15% of all CO2 emissions—about one and a half times as much as the poorest 50% [10]. Even within the Global North, it is often regions (e.g., neighborhoods) predominantly inhabited by members of disadvantaged groups that bear the brunt of climate impacts. Research from the United States shows, for instance, that hurricanes cause the most damage in neighborhoods where BIPoC and people with lower socioeconomic status live, and that heatwaves are particularly felt in poorer neighborhoods, which often lack greenery and vegetation [11]. Similar disparate climate change impacts disproportionately affecting BIPoC and people with lower socioeconomic status can be observed in other countries within the Global North [12].

Image 2: : People living in neighborhoods with limited greenery and tree cover are especially vulnerable to heatwaves.

Image 2: : People living in neighborhoods with limited greenery and tree cover are especially vulnerable to heatwaves.

Advocates for climate justice aim for a fair distribution of the burdens (and benefits) of climate change, both globally and within specific regions and communities, and the acknowledgement of previous injustices in climate policy decisions. This requires not only

distributive justice (e.g., ensuring that the costs of climate mitigation efforts are fairly distributed between and within countries) and restorative justice (e.g., compensating countries, regions, and communities disproportionately affected by climate change) but also

procedural justice [9].

Procedural justice demands that especially those communities that are most affected by climate change are able to actively participate in climate protection and policy-making processes. Against this backdrop, the underrepresentation of

BIPoC and people with lower

socioeconomic status in the climate movement appears almost paradoxical.

Psychological Strategies to Increase Diversity in the Climate Movement

Increasing the representation of

BIPoC and people with lower

socioeconomic status in the climate movement not only fulfills the demand for

procedural justice but is also essential for mitigating the negative impacts of climate change: As a global crisis, climate change requires worldwide, collective action from as many people as possible, transcending the boundaries of

social groups [8]. Moreover, increasing diversity in the movement can help shift the focus away from boundaries based on social categories such as race, ethnicity, and

socioeconomic status, while bringing commonalities between groups (e.g., the shared concern about climate protection) to the forefront. However, it is important that the original group memberships are not ignored in this process (as indicated by slogans like “We are all the same!”), as this risks overlooking and failing to address the still ongoing

discrimination faced by marginalized groups (see dual identity approach) [13].

Increasing diversity in the climate movement thus offers numerous benefits. Next, we outline two selected (social) psychological approaches that provide insights on how to achieve this

goal. Research from various fields shows that a diversity-sensitive external presentation of organizations (e.g., through a pro-diversity statement on a company’s website) might be an effective strategy to make organizations more attractive to members of underrepresented groups. Moreover, this approach may counteract the

stereotype that

BIPoC are less concerned about climate change than White people: Pearson and colleagues [3], for instance, demonstrated in their study that

BIPoC who viewed a website of a fictional environmental organization that explicitly emphasized diversity and also depicted non-White employees believed in this

stereotype to a lesser extent compared to those who viewed a website that did not highlight diversity and only depicted White employees. Such strategies may help underrepresented groups to feel welcomed in an organization, and may also establish or strengthen a perceived

social norm that climate protection is an important concern among

ingroup members. This, in turn, may mobilize individuals who were previously discouraged from participating in the climate movement due to misperceived social

ingroup norms. However, for such strategies to be effective, it is crucial to adhere to the principle that “actions speak louder than words.” Research suggests that pro-diversity statements can evoke distrust among members of underrepresented groups and carry the negative connotation of “diversity washing” if the

commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion is not also clearly reflected in the organization’s policies and structures (e.g., through explicit anti-

discrimination policies or diverse representation in leadership positions) [14]. If this is not the case, organizations should openly acknowledge the lack of diversity as a shortcoming and credibly demonstrate that steps are taken to increase diversity in the organization [15]. Transparent communication about existing diversity gaps and strategies to address them can foster trust among underrepresented groups. This, in turn, can help climate movements in their efforts to become more inclusive.

Another approach to enhancing diversity is a stronger focus on issues of climate justice within the climate movement. Research shows that

BIPoC and people with lower

socioeconomic status are more likely to perceive links between climate protection and issues of social inequality, racism, and poverty than White, middle-class people [16]. Explicitly addressing these topics and linking ecological goals (e.g., reducing CO2 emissions) with social goals (e.g., poverty reduction) could help previously underrepresented groups feel that their goals align with the climate movement’s goals. While climate justice is a key concern of many movements in the Global North, their focus is often on holding the Global North accountable for the negative effects of climate change for the Global South. Less attention, however, is given to the fact that some communities within nations in the Global North are also disproportionately affected by climate change. Moreover, a genuine

commitment to climate justice requires members of socially privileged groups to give up privileges and be willing to make

significant concessions (e.g., by paying higher taxes to mitigate negative climate impacts on socially disadvantaged groups). A clear articulation of such “redistribution goals” could further contribute to

BIPoC and people with lower

socioeconomic status to feel included and seen in the climate movement [17]. Lastly, a stronger integration of ecological and social goals could be achieved through coalitions between ecologically focused climate initiatives and other activist movements that prioritize social justice (e.g., alliances against racism or for fairer income distribution).

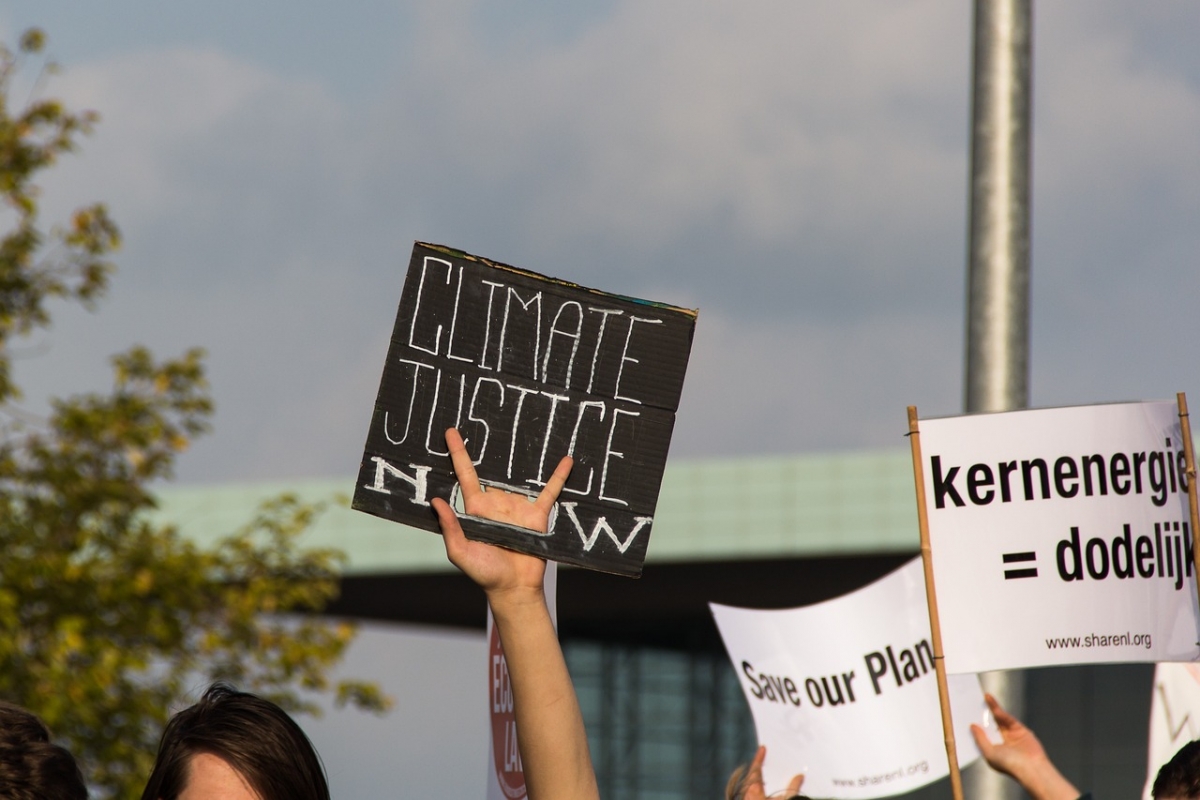

Image 3: Climate justice is increasingly being articulated as a goal by climate movements.

Image 3: Climate justice is increasingly being articulated as a goal by climate movements.

Conclusion

“Climate movements need to become more diverse!” Many climate activists and initiatives would probably agree with this statement—not only because as many people as possible need to be involved in climate protection, but also because the underrepresentation of the people and communities most affected by the negative impacts of climate change is increasingly recognized as a problem. This article highlights various barriers to the participation of

BIPoC and people with lower

socioeconomic status in climate movements and suggests approaches to increasing diversity. In closing, it is important to emphasize that the representation and inclusion of people from socially disadvantaged groups is not only an issue for climate movements. For instance, greater diversity in journalism (e.g., through more diversity-sensitive reporting) or in climate research (e.g., by focusing on different research priorities) could make a

significant contribution to

debunking existing

stereotypes and thus help create a more diverse climate movement.

1

BIPoC often experience a lower

socioeconomic status as well (e.g., due to a higher risk of poverty compared to White individuals), but for a substantial portion, this overlap does not exist. Therefore, the term “BIPoC and people with lower socioeconomic status” refers to people who belong to either of these groups or to both simultaneously.

PICTURE 1 SOURCE: https://pixabay.com/de/photos/demonstration-fridays-for-future-4891275/

PICTURE 2 SOURCE: https://pixabay.com/de/photos/blume-stra%c3%9fe-riss-gelb-allein-4346049/

PICTURE 3 SOURCE: https://pixabay.com/de/photos/klima-protest-manifestation-455713/

Bibliography

[1] M. Sommer, D. Rucht, S. Haunss, and S. Zajak, “Fridays for Future: Profil, Entstehung und Perspektiven der Protestbewegung in Deutschland,” (“Fridays for Future: Profile, origins, and perspectives of the protest movement in Germany”), Ipb Work. Pap. Ser., Feb. 2019, doi: 10.17169/refubium-4088.

[2] C. M. Bonam, H. B. Bergsieker, and J. L. Eberhardt, “Polluting Black space,” J. Exp. Psychol. Gen., vol. 145, no. 11, pp. 1561–1582, Sept. 2016, doi: 10.1037/xge0000226.

[3] A. R. Pearson, J. P. Schuldt, R. Romero-Canyas, M. T. Ballew, and D. Larson-Konar, “Diverse segments of the US public underestimate the environmental concerns of minority and low-income Americans,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 115, no. 49, pp. 12429–12434, Oct. 2018, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1804698115.

[4] T. Masson and I. Fritsche, “Adherence to climate change-related ingroup norms: Do dimensions of group identification matter?,” Eur. J. Soc. Psychol., vol. 44, no. 5, pp. 455–465, June 2014, doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2036.

[5] N. Geiger and J. K. Swim, “Climate of silence: Pluralistic ignorance as a barrier to climate change discussion,” J. Environ. Psychol., vol. 47, pp. 79–90, Sep. 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.05.002.

[6] T. M. Schusler et al., “Students of colour views on racial equity in environmental sustainability,” Nat. Sustain., vol. 4, no. 11, pp. 975–982, Aug. 2021, doi: 10.1038/s41893-021-00759-7.

[7] L. Cortina, D. Kabat-Farr, E. Leskinen, M. Huerta, and V. Magley, “Selective incivility as modern discrimination in organizations: Evidence and impact,” J. Manag., vol. 39, no. 6, pp. 1579–1605, Aug. 2013, doi: 10.1177/0149206311418835.

[8] N. A. Lewis Jr., D. J. Green, A. Duker, and I. N. Onyeador, “Not seeing eye to eye: Challenges to building ethnically and economically diverse environmental coalitions,” Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci., vol. 42, pp. 60–64, Dec. 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2021.02.025.

[9] A. R. Pearson, C. G. Tsai, and S. Clayton, “Ethics, morality, and the psychology of climate justice,” Curr. Opin. Psychol., vol. 42, no. 80, pp. 36–42, Dec. 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.03.001.

[10] B. Bruckner, K. Hubacek, Y. Shan, H. Zhong, and K. Feng, “Impacts of poverty alleviation on national and global carbon emissions,” Nat. Sustain., vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 311–320, Feb. 2022, doi: 10.1038/s41893-021-00842-z.

[11] C. J. Schell et al., “The ecological and evolutionary consequences of systemic racism in urban environments,” Science, vol. 369, no. 6510, Sep. 2020, Art. no. eaay4497, doi: 10.1126/science.aay4497.

[12] I. Ituen and L. T. Hey, “Kurzstudie: Der Elefant im Raum—Umweltrassismus in Deutschland. Studien, Leerstellen und ihre Relevanz für Klima- und Umweltgerechtigkeit,” (“Brief study: The elephant in the room—Environmental racism in Germany. Research, gaps, and their relevance for environmental and climate justice”), Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung e.V., 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.boell.de/de/2021/11/26/der-elefant-im-raum-umweltrassismus-d...

[13] J. C. Banfield and J. F. Dovidio, “Whites’ perceptions of discrimination against Blacks: The influence of common identity,” J. Exp. Soc. Psychol., vol. 49, no. 5, pp. 833–841, Sep. 2013, doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2013.04.008.

[14] L. Windscheid, L. Bowes-Sperry, D. L. Kidder, H. K. Cheung, M. Morner, and F. Lievens, “Actions speak louder than words: Outsiders’ perceptions of diversity mixed messages,” J. Appl. Psychol., vol. 101, no. 9, pp. 1329–1341, Sep. 2016, doi: 10.1037/apl0000107.

[15] L. Windscheid, L. Bowes-Sperry, K. Jonsen, and M. Morner, “Managing organizational gender diversity images: A content analysis of German corporate websites,” J. Bus. Ethics, vol. 152, no. 4, pp. 997–1013, Nov. 2018. [Online]. Available: http://www.jstor.org/stable/45022782

[16] H. Song et al., “What counts as an ‘environmental’ issue? Differences in issue conceptualization by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status,” J. Environ. Psychol., vol. 68, Apr. 2020, Art. no. 101404, doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101404.

[17] H. R. M. Radke, M. Kutlaca, B. Siem, S. C. Wright, and J. C. Becker, “Beyond Allyship: Motivations for Advantaged Group Members to Engage in Action for Disadvantaged Groups,” Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev., vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 291–315, May 2020, doi: 10.1177/1088868320918698.