Can you nonbelieve it: What happens when you do not believe in your memories?

What explains the discrepancy in frequency of nonbelieved memories elicited by direct and indirect cueing methods? Well, perhaps there is no real discrepancy. Although 25% of people have salient nonbelieved memories when you interview them systematically about them, the accessibility rate to nonbelieved memories in daily retrospection might be quite low (3-6%), and understandably so: why bother about something that you do not believe. Indeed, an interesting question is: how do nonbelieved memories affect people’s attitudes and behaviour? For instance, will nonbelieved memories of sexual abuse influence retractors’ attitudes toward the family members that they previously accused of the abuse? Or will their vivid nonbelieved memories hinder the attempts of retractors to restore their relationship with their families? In order to address these questions, researchers have developed ways to experimentally evoke nonbelieved memories in the laboratory.

Not Believing a Hot Air Balloon Experience

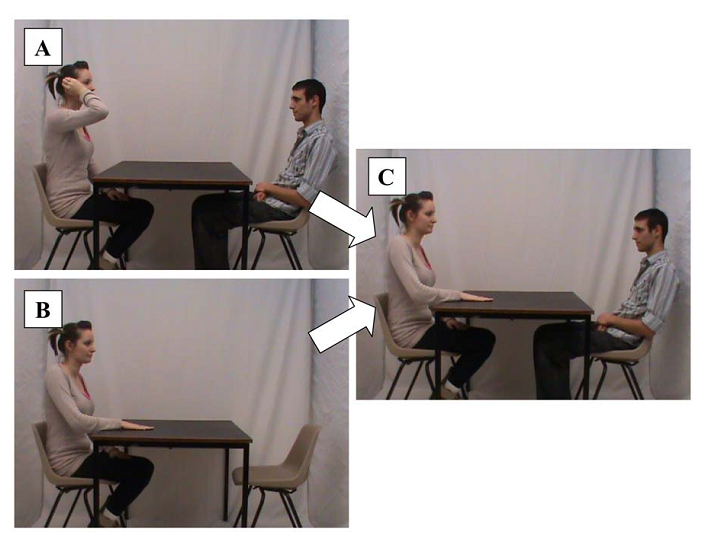

Besides studying naturally occurring nonbelieved memories, researchers have examined whether nonbelieved memories can be elicited in the laboratory. Although a plethora of research has revealed that repeatedly suggesting that a false event occurred increases confidence, belief, and even recollection for that event (Koehler, 1991), our knowledge about how to undermine belief is still quite limited. In one demonstration, Clark, Nash, Fincham and Mazzoni (2012) provided participants with fake videos (i.e., doctored-video paradigm; Nash, Wade, & Lindsay, 2009) to create nonbelieved memories. Participants were first asked to perform some actions such as clapping their hands and rubbing the table while their actions were being video recorded. Two days later, participants watched a doctored video edited by the researchers in which fake actions were embedded and in this way, participants falsely “remembered” and “believed” that they had performed the fake actions. Finally, researchers told them that actually the video clip was doctored and then measured their belief and recollection for the action. This manipulation undermined participants’ belief for 14% to 26% of the fake actions but vivid recollections for these fake actions remained.

Figure 1. Doctored video clip. (A) Real clip. (B) Fake action. (C) Doctored composite of (A) and (B). From Clark, A., Nash, R. A., Fincham, G., & Mazzoni, G. (2012). Creating non-believed memories for recent autobiographical events. PLoS ONE, 7(3): e32998. Copyright 2012 by Andrew Clark. Reprinted with permission.

In another demonstration, Otgaar, Scoboria, and Smeets (2013) used a false memory implantation procedure to experimentally elicit nonbelieved memories in children and adults. The false memory implantation method is known as an effective manipulation to create vivid mental representations for suggested false events in both children and adults (see Otgaar, Verschuere, Meijer, & Van Oorsouw, 2012). In this paradigm, individuals were: (1) provided with the narrative of a fictitious event such as a hot balloon ride when they were children; (2) guided by the experimenter to mentally “travel” back to the suggested event and think about or imagine the details of that experience; and (3) asked whether they had formed a memory for the false event across multiple interviews. Typically about 30-40% of individuals will report strong memories and beliefs for the suggested false events (Wade, Garry, Read, & Lindsay, 2002).